- Date:

- 24 Oct 2023

Intersectionality at Work is a companion report to the Baseline Report 2021, released in 2022 following the inaugural workplace gender audit.

It provides insights and analysis of intersectional data collected by defined entities as part of the audit. This analysis is combined with findings from projects funded as part of the Commission's Research Grants Round 2022.

Intersectionality at Work will assist the Commission, defined entities, and the Victorian community to understand:

- how experiences of disadvantage and discrimination on the basis of intersectional attributes might compound or shape experiences of gender inequality

- where to focus efforts to improve.

Acknowledgement of Country

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector acknowledges and pays respect to the traditional owners of Country throughout Victoria.

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector acknowledges and pays respect to the Traditional Owners of the lands on which we are proud to be located. Our office is based on the lands of the Wurundjeri people – the lands on which many of our team members also live and work from home. Other team members live and work on Bunurong land and Dja Dja Wurrung land.

We also acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of Country throughout Victoria and pay our respects to them, their cultures, and their Elders past and present. We recognise the deep and enduring connection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to Country and their continuing custodianship of the land, waterways and seas.

We proudly recognise the First Nations peoples as having the world’s oldest living cultures, and acknowledge that the heritage, traditions and customs of Aboriginal communities throughout Victoria are vibrant, rich and diverse. We value this knowledge and consider it a source of strength and opportunity.

We respect that Elders and other leaders of Aboriginal communities in Victoria are critical to redressing inequality and disadvantage and improving outcomes for Victorian women. Their leadership includes First Nations women, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, non-binary, sistergirls, brotherboys, intersex and queer folk who drive gender equality across Victoria. We thank them and honour their important work.

As we reflect on the continuing impact of government policies and practices, we recognise our responsibility to collaborate and work together with First Nations peoples, families and communities towards improved economic, social and cultural outcomes.

Message from the Minister for Women

Victoria is the first and only jurisdiction in Australia to have formally integrated intersectionality into equality law. The Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) reflects the Victorian Government’s commitment to ensuring that no Victorian is left behind when it comes to addressing the overlapping systemic and structural drivers of gender inequality. This acknowledgement is critical, as it recognises the diversity of lived experience across Victoria – without it, those most vulnerable in our community will continue to be disproportionately impacted by gender inequality.

Last year, the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector released Victoria’s first ever public sector Baseline Report, which highlighted key data from the first workplace gender audits completed under the Act in 2021.

I am pleased to present the Commission’s Intersectionality Report - Intersectionality at Work: Building a baseline on compounded gender inequality in the Victorian public sector, a companion to the Baseline Report.

This report demonstrates Victoria’s leadership in championing intersectional gender equality, a key theme of Our equal state: Victoria’s gender equality strategy and action plan 2023-2027.

This report analyses workforce and survey data about employees who experience compounding forms of disadvantage and discrimination. It also incorporates key findings and recommendations from intersectional research funded by the Victorian Government.

Thank you to the organisations who collected and submitted this crucial information, as well as the researchers who have helped build the evidence base regarding intersectional gender equality in Victoria’s public sector workplaces. I look forward to sharing these findings and recommendations widely as Victorian public sector organisations prepare to report on their gender equality action plan progress and Victoria strengthens its position as a leader in advancing intersectional gender equality.

We want to ensure that the voices of all Victorians, especially those that are marginalised, are heard so we can all live in a fair and equal state.

The Hon Natalie Hutchins MP

Minister for Women

Message from the Commissioner

Victoria's first Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner is pleased to deliver 'Intersectionality at work: building a baseline on compounded gender inequality in the public sector'.

As Victoria’s first Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner, I am pleased to be delivering Intersectionality at work: building a baseline on compounded gender inequality in the Victorian public sector, a companion to the Commission’s 2021 Baseline report. In this report, we have analysed intersectional workforce and survey data from across the Victorian public sector, and drawn on research funded by the Commission, to provide an overview of the state and nature of intersectional workplace gender inequality in Victoria.

For the first time in 2021, almost 300 organisations covered by the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) collected and submitted intersectional workforce and employee experience survey data to the Commission. As with many firsts, when defined entities submitted their intersectional data, the Commission found significant data gaps and inconsistencies in the way this data was collected and provided. This made it difficult to collate and analyse the data accurately and meaningfully. As a result, in our Baseline report we committed to funding a suite of intersectional research and to taking the additional time needed for the more complicated data analysis required, with the goal of releasing this companion report in 2023.

I want to thank all the staff who supported their organisations to prepare and submit this data, as well as the researchers who have played a key role in helping the Commission to build a foundational evidence base of intersectional insights. The collection and analysis of this data marks a crucial and long overdue shift in the maturity of how we understand gender inequality. This report shows that compounding forms of discrimination have notable impacts on career progression, pay inequality, and the experience of sexual harassment and discrimination at work. As such, an intersectional approach to gender equality is no longer a nice to have, it’s a must have – without it, our work will continue to reproduce some of the very patterns of inequality we seek to address.

Research we commissioned in 2021 and 2022 found that despite the existence of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives across the Victorian public sector, women facing intersecting forms of discrimination continue to experience disproportionate levels of workplace discrimination. When data on intersectional attributes is collected, these experiences become visible. The use of an intersectional lens in data collection, analysis and interpretation will help us to identify the unique barriers marginalised people face in the workplace. This will, in turn, help us curate impactful, tailored solutions to these issues.

There are significant improvements that need to be made at an organisational level to create a culture of safety across workplaces, so staff feel comfortable sharing intersectional data. Findings from our 2021 and 2022 research grants show that reports of discrimination and harassment are not being properly addressed at the managerial level. Intersectional gender inequality is everyone’s business, and senior leaders in particular, have a positive duty and responsibility to ensure that workplaces take action to achieve gender equality from the top-down. Leaders must actively model, prioritise and drive a culture of safety in their organisation and ensure accountability and buy-in from middle managers. Without this, DEI initiatives will fail to challenge structural inequalities, as staff are expected to assimilate into the existing status-quo.

I want to recognise the effort that has gone into creating this report – the first of its kind in Australia to collate and analyse intersectional public sector workforce data. While there is still much progress to be made, I am confident that Victoria will continue to lead by example in addressing the overlapping systemic and structural drivers of gender inequality within the workforce, inspiring other jurisdictions to do the same.

Dr Niki Vincent

Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner

Executive Summary

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector is driving intersectional gender equality through the Gender Equality Act.

Driving intersectional gender equality through the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic)

Under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) organisations covered by the Act ‑ known as defined entities – are subject to a number of obligations that require them to take positive and transparent action towards achieving gender equality in their workplaces and in their public policies, programs and services.

One part of what makes the Act nation leading is that it explicitly invokes the concept of compounded inequality (Ryan et al. 2022). The Act states that, where possible, the data that defined entities collect should capture not only gender, but also intersecting forms of disadvantage or discrimination that a person may experience based on Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion, sexual orientation and other attributes. The Act requires defined entities to use this data to drive positive and transparent progress towards intersectional gender equality.

The Commission is committed to supporting defined entities to meet their obligations under the Act through improved training, education, and guidance resources. This report represents the first step in building a baseline for ongoing progress on intersectional gender equality in Victoria. Across 5 chapters, it investigates how the intersection of gender and one other attribute (Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, age, ability, cultural and racial marginalisation, and LGBTIQ+ status) shape workplace experiences. These findings demonstrate how gender inequality is compounded by other forms of discrimination in the Victorian public sector, offering useful starting points for organisations considering how to best implement meaningful change.

The pay gaps experienced by people facing intersecting inequalities must be closed

The Commission’s audit data demonstrates that many groups that face intersecting forms of discrimination and disadvantage experience significant pay gaps. Pay gaps were largest between First Nations women when compared with non-Indigenous men, at 21% across all industries covered by the Commission’s audit data. The public health industry recorded the largest pay gap between these two groups at 35%. While the pay gaps between First Nations men and non-Indigenous men (12%), and non-Indigenous women and men (15%) were also high, the much larger gap in salaries for First Nations women clearly demonstrates the negative and compounding effects of inequality based on gender and First Nations status. However, no pay gap should remain unaddressed.

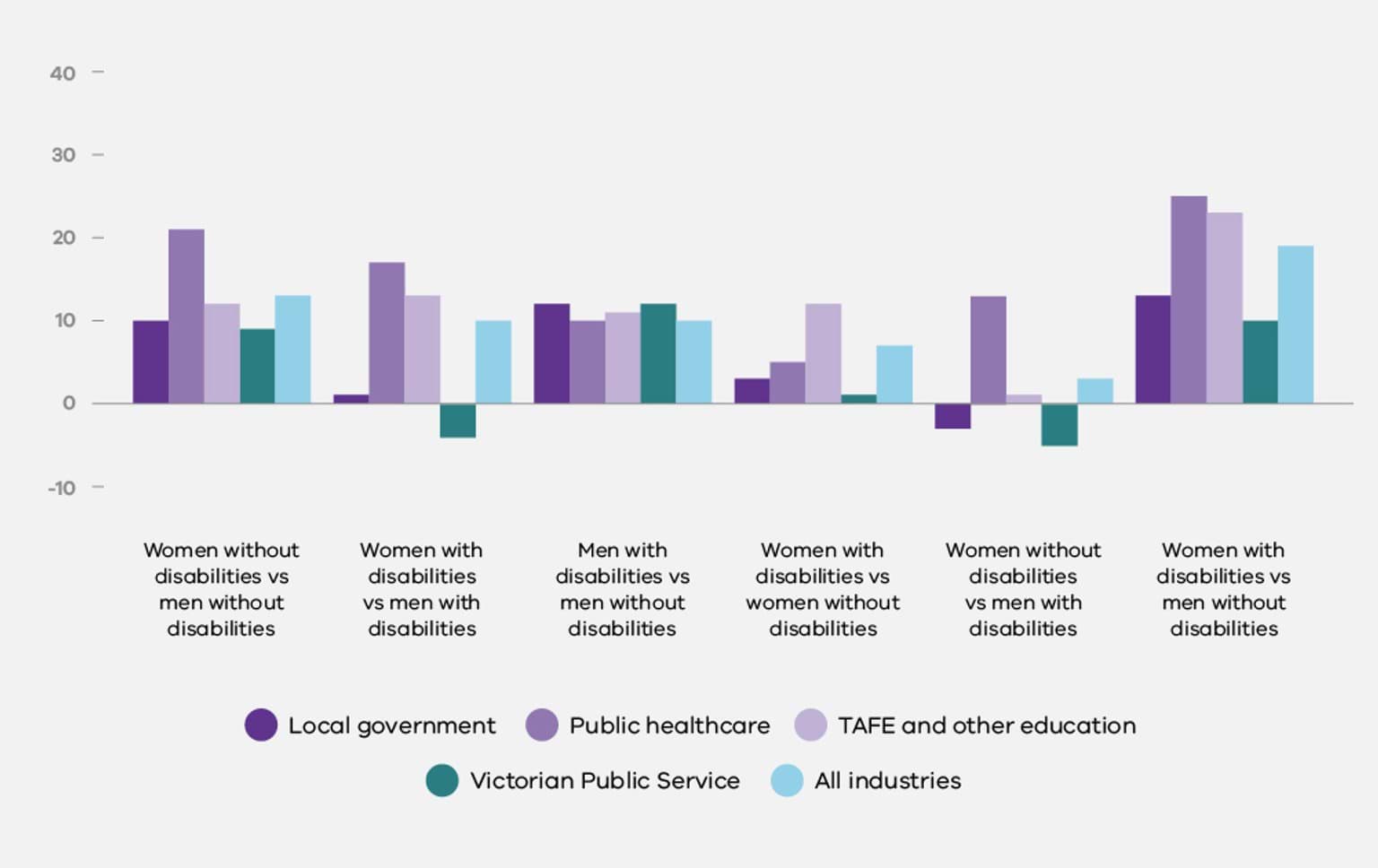

Likewise, the Commission’s audit data demonstrated that women with disabilities experienced large pay gaps when compared with men without disabilities, at 19% across all industries. The pay gap between men with disability and men without disability was approximately half the above at 10%, while the pay gap between women and men without disabilities across all industries was 13%, again demonstrating the negative and compounding effects of inequality based on gender and ability. Women with disability also had lower levels of confidence in the promotion practices in their organisations. This may indicate barriers to accessing career progression that could further impact the salaries of women with disabilities. Further research is required to understand these connections.

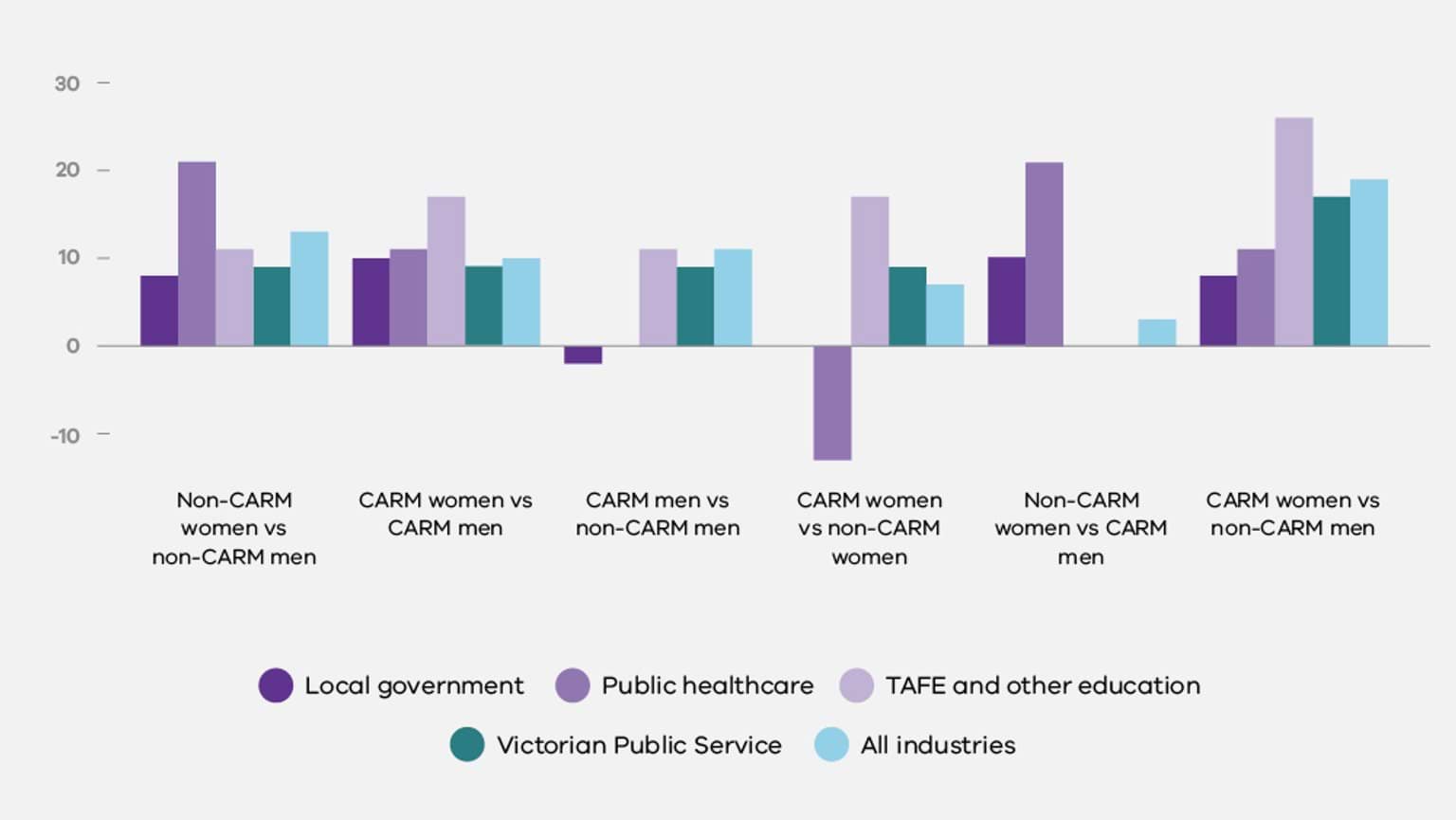

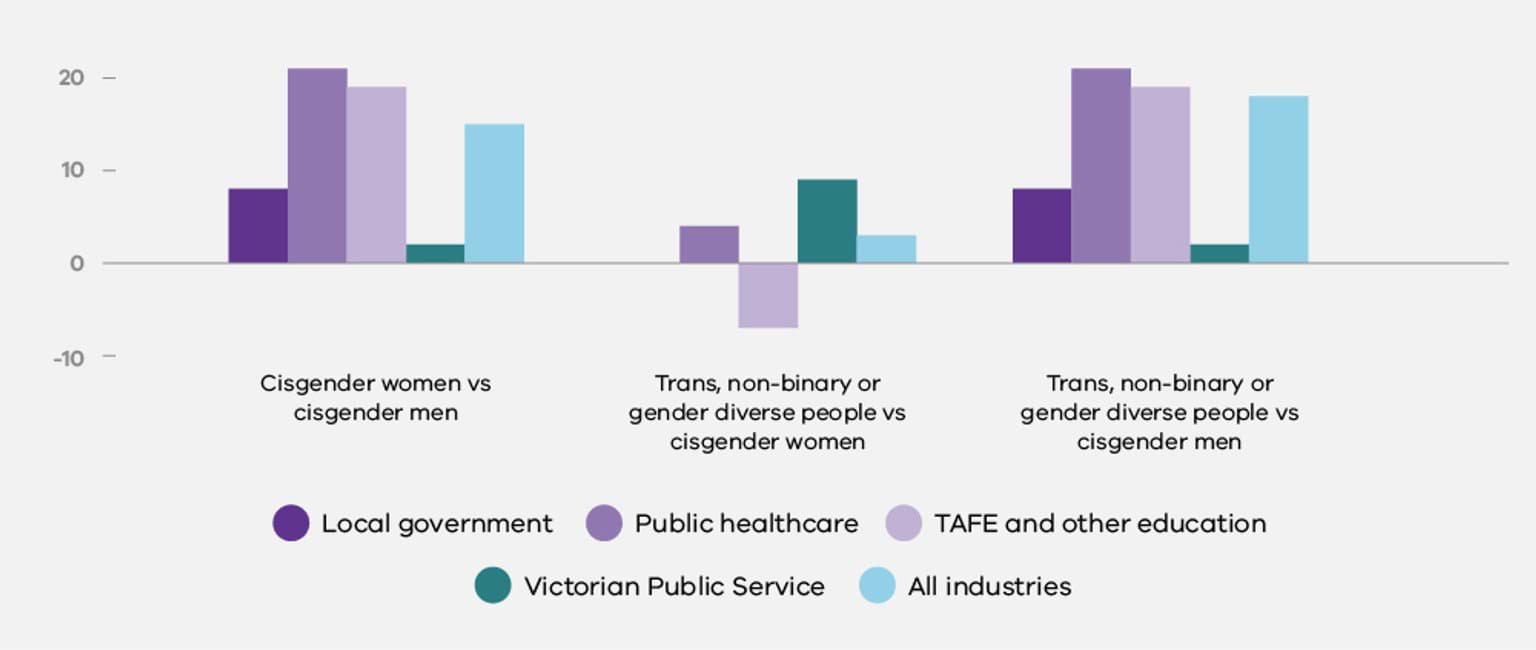

Pay gaps were also significant between culturally and racially marginalised (CARM) women and non-CARM men (19%), and between trans, non-binary and other gender diverse employees and cisgender men, both at 18%. The pay gaps between CARM men and non-CARM men (11%) and non-CARM women and men (13%), as well as between cisgender women and cisgender men (15%) – while still high – were notably smaller. As stated above, no pay gap should go unaddressed. However, these findings again highlight the negative and compounding effects of gender and CARM status on pay inequality.

High rates of sexual harassment among certain groups require urgent attention

Younger women, people with disabilities and LGBTIQ+ people reported experiencing markedly high rates of sexual harassment in Victorian public sector workplaces. Fourteen per cent of women aged 15-24 and 11% of women aged 25-34 reported experiencing sexual harassment in the previous 12 months. This compares to 4% and 5% respectively of men in the same age groups.

Twelve per cent of women with disabilities reported experiencing sexual harassment, a figure 4% higher than men with disability, twice the rate of women without disabilities, and 4 times the rate of men without disabilities. These findings reflect existing research, which has described rates of sexual violence against women with disability in Australia as ‘endemic’ (Dowse et al. 2016). The relatively higher rate of the experience of sexual harassment reported by men with disability also demands attention.

While gay men and straight women reported similar rates of experience of sexual harassment (7% and 6% respectively) this was double the rate reported by straight men (3%). All other non-heterosexual women and men reported much higher rates of the experience of sexual harassment (between 10-15%). Transwomen and other trans, non-binary or gender diverse people also reported far higher rates of experiencing sexual harassment (16% and 15% respectively) than transgender men (8%) and cisgender women (6%) and men (4%). Thus, while the experience of sexual harassment is unacceptable for anyone, this is an issue of particularly urgent concern for those who are not cisgendered men and/or straight men.

The underrepresentation of CARM women in senior positions across the Victorian public sector is concerning

Only 3% of CARM women reported that they held a senior management role, and only 9% were in a supervisory position (compared with non-CARM men at 14% and 21% respectively). While CARM women experience even worse leadership outcomes than other disadvantaged groups, such as First Nations women (with representation at 6% and 11% respectively), women with disabilities (with representation at 5% and 12% respectively) and transwomen (at 4% and 10% respectively), the low representation of all these groups of women in senior management and supervisory roles needs to be addressed. It is notable that CARM men are also poorly represented in leadership positions, with only 6% in senior manager roles and 13% in supervisory positions - similar to non-CARM women at 7% and 15% respectively, and with comparable pay gaps in some industries.

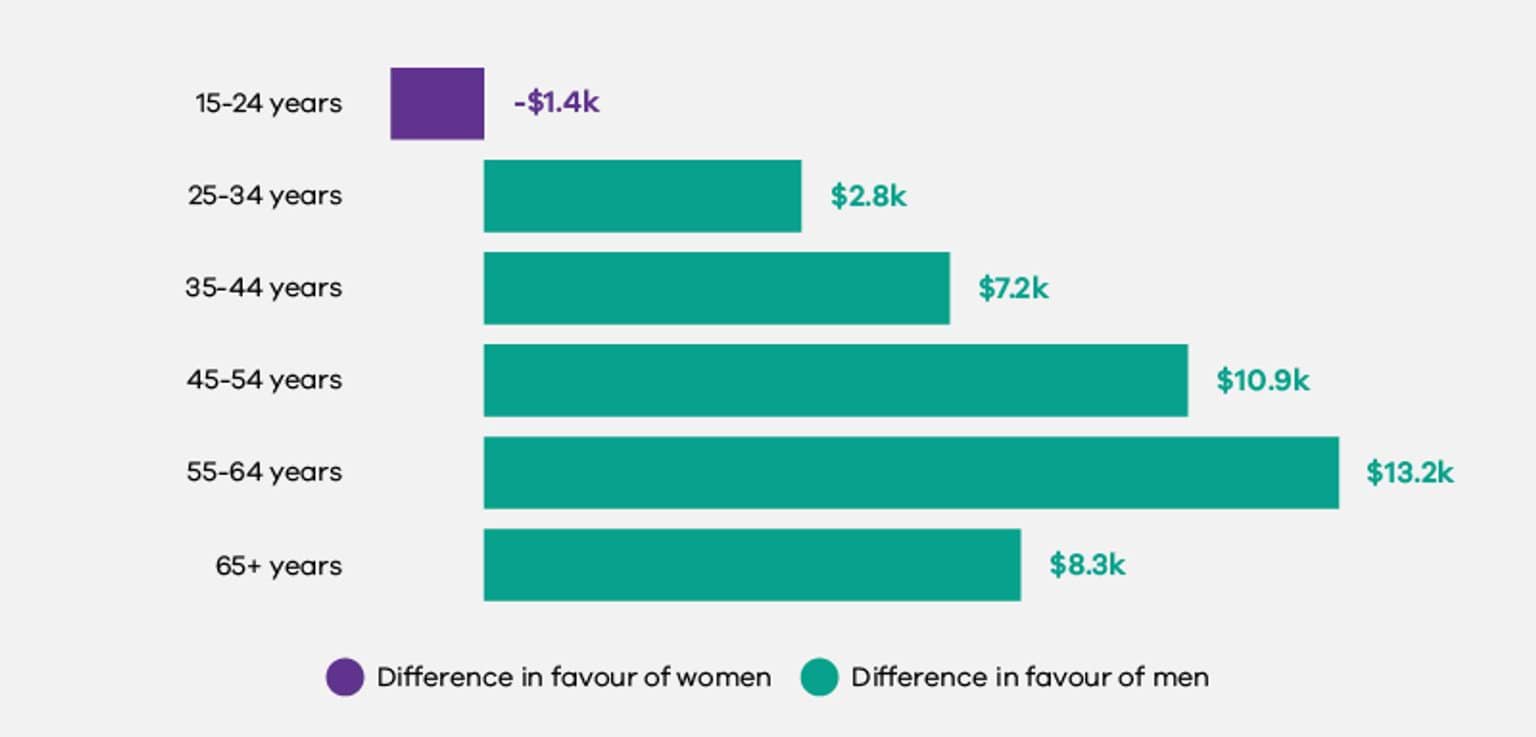

Age continues to amplify women's experiences of workplace gender inequality

As noted above, the Commission’s data demonstrates that age and gender combine to increase the risk of sexual harassment for young women in the Victorian public sector. Women at the midpoint of their careers also experience the compounded effects of gender and age discrimination, with pay gaps widening and leadership opportunities diminishing. In this stage of life, gendered norms around care work begin to significantly impact upon women’s ability to prioritise their careers in the same way as men. Over time, the compounding effects of age and gender discrimination result in a gender pay gap favouring men in every age bracket increasing from 25-34 until 55-64, after which it tapers off slightly.

Organisations must do more to address the negative workplace experiences of some LGBTIQ+ employees

There is a troubling lack of available data pertaining to the experiences of non-binary and gender diverse people. These groups report lower salaries than their cisgender colleagues and are the least likely of any gender identity to agree that recruitment and promotion process in their organisation are fair. Better data collection in relation to gender diverse employees will help to make the experiences of this cohort visible. Better data is also crucial to grounding and focussing interventions to address the issues.

Lesbian women are an exception to the wider finding that women facing compounding inequalities tend to experience an income penalty

Lesbian women in the Commission’s data set had, on average, higher salaries than bisexual and pansexual men and women in all other sexuality groups. Lesbian women also held managerial positions at a similar rate to both straight and gay men. This finding could point to lesbian women’s increased ability to avoid traditional heterosexual divisions of labour, enabling them to focus more on their career development. Further research is required to better understand these findings.

The Commission’s data may signal positive change in relation to diversity, inclusion and safety in some areas

Indigenous and non-Indigenous women and men were roughly equally likely to report that the recruitment and promotion practices in their workplace were fair. CARM women and men also reported lower instances of sexual harassment than their non-CARM colleagues of the same gender. However, it is unclear whether these more promising findings indicate that groups experiencing intersectional discrimination face fewer instances of workplace inequality in public sector workplaces compared to other sectors, or whether they are instead indicative of reporting challenges which can skew the accuracy of data.

In the case of sexual harassment reporting in particular, data accuracy is known to at times be limited, because diverse groups may understand or identify incidences of sexual harassment differently (Respect@Work n.d). However, the fact that the People matter survey (PMS) is an anonymous survey that asks questions about experiences of specific behaviours is a positive sign that diverse employees in Victorian public sector workplaces may feel less discriminated against and experience lower rates of sexual harassment than diverse workers in some other sectors. The Commission’s sexual harassment reporting data may have also been skewed in this reporting period by the COVID-19 context, where public sector workers were likely to be working from home rather than in the office. Given the Commission’s funded research highlights the continued negative workplace experiences of both First Nations and CARM women, there is still work to be done to ensure workplace gender equality for all (Bargallie et al. 2023; Cho and Segrave 2023).

Better data is crucial for ensuring better workplace outcomes for everybody

Improved intersectional data collection practices, built on the inclusion of diverse voices, are crucial for driving positive change in organisations. Organisations must carefully consider their approach to intersectional data collection, analysis and interpretation. At every stage of the data collection, analysis and interpretation process, organisations should meaningfully engage diverse voices in their organisation to ensure that their practices and approach to addressing intersectional gender equality are reflective of, and responsive to, lived experiences of disadvantage and discrimination in their workplaces. Demonstrating commitment to consultation and meaningful input from diverse voices will also help organisations to build the trust and accountability necessary for individuals to feel comfortable sharing their personal information.

Introduction

An introduction to the Gender Equality Act 2020 and this Intersectionality at Work report, including methodology and structure of the report.

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector (the Commission or CGEPS) was established after the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) passed in February 2020. The Commission supports the Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner (the Commissioner) to oversee the implementation of the Act and promote gender equality in the public sector workforce and the broader Victorian community.

The Act is a ground-breaking piece of legislation that requires certain public sector organisations in Victoria to take positive action towards achieving gender equality in the workplace and the community. It does so by requiring these organisations to:

- Report on key gender equality measures by undertaking a workplace gender audit every 2 years;

- Demonstrate how they plan to improve gender equality in their organisation by developing a Gender Equality Action Plan every 4 years;

- Make reasonable and material progress in relation to the Act’s workplace gender equality indicators every two years; and

- Account for the gendered impacts of all policies, programs and services with significant public impact by undertaking gender impacts assessments.

Organisations with obligations under the Act (referred to as ‘defined entities’) include all Victorian public sector organisations with 50 or more employees as at June 30 each year, as well as local councils and universities.

The Act represents an ambitious step up in equality law in Australia, by imposing a positive duty on defined entities to consider and promote gender equality. It is also the first piece of Australian legislation to officially acknowledge the potential for compounding effects of multiple forms of disadvantage or discrimination. This focus on the way in which gender inequality can be compounded by other forms of inequality was a key request from community groups and other participants during the Act’s consultation process.

For a more detailed background to the Act and the Commission, please see the companion to this report, the Baseline report (2022).

This report

Organisations covered by the Act are subject to several obligations that require them to take positive and transparent action (and make meaningful progress) towards achieving gender equality in their workplaces, public policies, programs and services. For the first time under Australian gender equality reporting legislation, these organisations are encouraged to provide data disaggregated not only by gender, but across a range of attributes listed in the legislation:

- Aboriginality

- age

- disability

- ethnicity

- gender identity

- race

- religion

- sexual orientation

- other attributes.

Through this data collection, organisations are encouraged to consider how experiences of disadvantage or discrimination on the basis of these attributes might compound or shape experiences of gender inequality. That is, organisations are encouraged to consider intersectionality.

In this report, the Commission presents an analysis of the data collected by defined entities as part of the inaugural workplace gender audit under the Act undertaken in 2021. This analysis is combined with findings from projects funded as part of the Commission’s Research Grants Round 2022.

This report is intended to be read as a companion piece to the Baseline report – 2021 workplace gender audit data analysis, which the Commission released in 2022 following the inaugural audit. The Baseline report presented a snapshot of the state and nature of gender equality across the 298 defined entities that were required to report under the Act at that time. In so doing, it offered the Commission, defined entities and the wider Victorian community a starting point for tracking change against the seven gender equality indicators under the Act (outlined below). In addition, it helped to locate the gaps and challenges for progressing gender equality in Victoria and offered insights into how defined entities can best target efforts towards positive change.

Through its reporting platform, the Commission collected 67 million data points in 2021, which represents the most comprehensive gender-disaggregated dataset on public sector organisations in Australia. Despite the significance of the scope of this data, the inaugural audit also revealed several areas of limited data availability and poor data quality - particularly in relation to data about people who experience intersecting forms of disadvantage and discrimination. Many organisations required to report under the Act are continuing to develop the necessary human resources systems to collect data about employee identity in a sensitive manner. These data challenges at the organisational level translate into challenges for rigorous data analysis for the Commission. Additionally, the sensitive nature of data related to the personal attributes of individuals meant that the Commission felt a significant responsibility to analyse and represent this information accurately and meaningfully. For this reason, the Commission chose to release this separate report, allowing time to carefully interrogate the data and ensuring that the data about people experiencing intersecting forms of disadvantage and discrimination were given due focus and attention.

What is intersectionality?

Intersectionality is a term that was coined in 1989 by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw to explore how systems of power, such as gender, race, and class, ‘intersect’ to shape experiences of the social world. Originally set out in the context of legal scholarship, Crenshaw (1989) was concerned that legal decisions dealing with racial discrimination and sex-based discrimination were failing to conceptualise how, for example, Black women’s experiences are shaped by racism as well as sexism, and by a unique combination of both. In other words, Crenshaw argued that when Black women are treated as purely Black or purely women, the law is unable to account for the specific challenges they face – challenges which diverge from those faced by Black men or white women (see also Moraga and Anzaldúa 1981; Collins 1990).

Since 1989, public awareness of the importance of intersectionality for understanding issues of discrimination and disadvantage has grown dramatically. While there are still debates in relation to intersectionality theory and its application (e.g. Collins and Chepp 2013; Cho and Segrave 2023), understanding how discrimination on the basis of attributes such as Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion, and/or sexual orientation can combine with gender discrimination to influence a person’s workplace experiences and outcomes is crucial to ensuring progress towards gender equality is progress for all.

Measuring and applying intersectionality

Approaches to ‘doing’ intersectionality in the workplace, including applying an intersectional lens to workforce data, are still being developed and often have limitations (Blackham et al. 2024 forthcoming). Despite these challenges, considering intersectionality in workplace equality initiatives is important. The Commission is committed to continuous improvement in relation to fulfilling the intersectional objectives of the Act, and to helping defined entities build their capability to progress intersectional gender equality.

In this report, the Commission has only been able to consider the kinds of inequalities produced by gender-based discrimination and one other axis of marginalisation, for example, gender and disability, or gender and Aboriginality. In reality, the lives of Victorians are much more complex than this. For example, people with disability may also be members of the LGBTIQ+ community, have demanding caring responsibilities, live in rural towns without adequate services, and/or belong to migrant communities (for further information on gendered experiences in rural contexts, see Tischler et al. 2023). Accounting for these differences is crucial to understanding the lived experiences of Victorian employees. However, while generalisations can mask significant variations in the experiences of members within a marginalised group, they are often necessary to identify broader trends. The ‘gender-plus-one-other-attribute’ approach here is designed to focus on patterns of systemic inequality and respond to practical considerations related to the data.

Finally, the Commission shines a spotlight on groups which face discrimination and disadvantage in this report, but it does not mean to imply that these groups are disempowered. Instead, the report strives to centre their voices as well as their ongoing activism and courage in the face of systemic discrimination. In the past, government data collection about marginalised groups was sometimes used against those groups (D’Ignazio and Klein 2020; Kukutai and Taylor 2016). Collecting data about people therefore comes with responsibility, and the Commission is committed to using data to drive positive social change. Better data is key to driving change initiatives which are responsive to the lived experiences of employees. Their voices and partnerships are crucial for providing the necessary scaffolding to accurately interpret quantitative data points. The Commission engaged lived-experience expertise at various points in the development of this report, as outlined below.

Methodology

Background

Under the Act, every defined entity was required to undertake a workplace gender audit in order to assess the state and nature of gender inequality in its workplace as at 30 June in the Gender Equality Action Plan reporting year. The first reporting year was 2021.

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector published workplace gender audit guidance in 2020 to advise defined entities of how to undertake a workplace gender audit.

The workplace gender audit required the collection of gender-disaggregated data – which is data that is broken down separately for women, men and gender diverse people – against the 7 workplace gender equality indicators set out in the Act. The indicators are:

- gender composition of all levels of the workforce

- gender composition of governing bodies

- equal remuneration for work of equal or comparable value across all levels of the workforce, irrespective of gender

- sexual harassment in the workplace

- recruitment and promotion practices in the workplace

- availability and utilisation of terms, conditions and practices relating to family violence leave, flexible working arrangements and working arrangements supporting workers with family or caring responsibilities

- gendered segregation within the workplace.

If available, defined entities were also required to report data about Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion and sexual orientation and were required to have regard to the disadvantage or discrimination that a person may experience on the basis of these attributes in addition to gender inequality (i.e. compounded or intersectional gender inequality).

Data measures and types

As part of the 2021 workplace gender audit, organisations covered by the Act collected two categories of data – workforce data and employee experience data. The workforce data was extracted from defined entities’ internal data collection systems and provided to the Commission through an Excel template that was uploaded through the Commission’s reporting platform. The employee experience data was collected through surveys.

Information provided to the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector was managed in line with relevant privacy laws. Defined entities were responsible for their own compliance with relevant privacy laws, including the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) (PDP Act).

Workplace gender audit data quality

The most common issue observed with audit submissions was missing data. The inaugural audit was the most comprehensive workforce data collection exercise many organisations had ever undertaken, so some gaps in datasets were anticipated by the Commission.

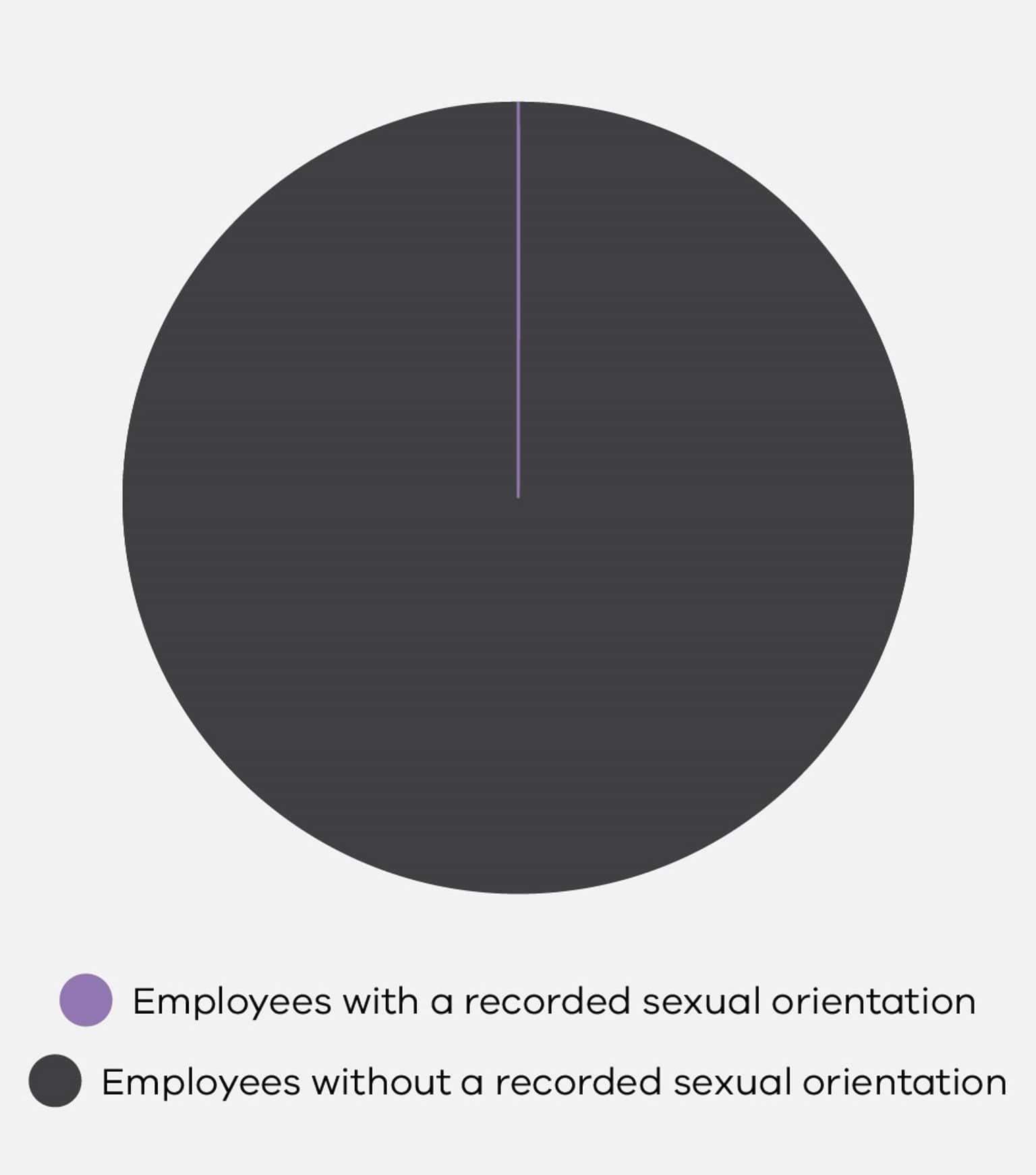

Aside from age and gender, the Commission learnt that most organisations do not yet collect the demographic data required for intersectional analysis. Because of this, the anonymous People matter survey, outlined below, is the primary source of data analysed in this report.

Furthermore, the 2021 workplace gender audit also contained very little workforce data in relation to gender diverse employees. While the People matter survey data that is the focus of this report included trans and gender-diverse respondents, the number of respondents in these groups who identified themselves as also being a First Nations person, a person with disability, or from a culturally and racially marginalised background were too few to meaningfully analyse. As such, the experiences of trans and gender-diverse employees are primarily discussed in Chapter 5, which examines LGBTIQ+ workers specifically. In this report, the Commission acknowledges this lack of data on trans and gender-diverse people has meant that issues are generally only able to be analysed and discussed for women and men.

Employee experience data and the People matter survey

In order to fulfil the employee experience data component of the workplace gender audit in 2021, organisations had three options:

- undertake the People matter survey or the People matter survey for local government (collectively referred to in this report as the People matter survey, or PMS) administered by the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC)

- use a third-party provider to independently administer the survey

- conduct the survey in-house.

The VPSC administered the questions required by the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector via the People matter survey to about 90% of organisations covered by the Act. Each organisation covered by the Act was surveyed separately, and the results were reported as percentages of respondents. Items with fewer than 10 responses were suppressed by the survey provider to protect respondents’ privacy.

The VPSC also provided the raw survey data for all participating defined entities to the Commission in late 2022. That is, the Commission has access to a results database that includes the responses to the required 2021 workplace gender audit questions from each individual respondent in a participating defined entity. The analyses undertaken in this report using People matter survey data are based on this raw data. This allows the Commission to calculate percentages for different groups across the whole dataset.

In this report, the Commission’s analysis of the People matter survey data includes data from all defined entities that participated in the survey. This includes local government organisations who opted to take part. It excludes any organisation which was not a defined entity in 2021 but has since become so. It also excludes universities, bodies which do not take part in the People matter survey, or any public sector organisation that was eligible to participate in the People matter survey, but opted out.

It is important to note that the People matter survey data analysed here is a different sample to that used by the Victorian Public Sector Commission. The VPSC’s reporting of the People matter survey results does not include local government organisations. It does, however, include smaller public sector organisations that do not meet the threshold to become defined entities under the Act. These differences are responsible for any discrepancies between these analyses.

It is also important to acknowledge the differences between the analyses contained in this report, and the data presented in the Commission’s 2022 Baseline report. The Baseline report primarily analysed the 2021 workplace gender audit workforce data. As such, workforce figures reported reflect the total number of employees reported on by organisations that completed a 2021 audit. Because the current report draws more extensively on the People matter survey data, the figures are reporting on a different population. Not only does the People matter survey data only cover approximately 90% of organisations with reporting obligations under the Act, but individual employees also choose whether or not to complete the survey. As such, rates of – for example – part-time work reported in the People matter survey may differ from rates of part-time work reported in the workforce data. Any apparent discrepancies between the Baseline report and this Intersectionality report stem from the different populations being examined.

Key characteristics of the People matter survey dataset analysed here by the Commission are that:

- The sample included 106,069 respondents of which 30% (31,443 people) were men, 58% (61,706 people) were women, 1% (580 people) were non-binary, 0.3% (347 people) reported a self-described gender and 11% (11,993 people) of people opted to not report a gender

- The VPSC reported survey results had an overall response rate of 39% - the Local Government portion of the survey had a 32% response rate

- The salary distribution of respondents does not match those found in the workforce data reported to the Commission, with people on lower salaries over-represented in the survey.

It should also be noted that some participants elected to use the available free-text field to describe their gender, rather than selecting from the available options. These responses have been excluded from the analysis in this report. This is because these responses are not homogenous and cannot be analysed as a group. In addition, given these respondents explicitly chose not to select from the available options, they cannot be integrated into the existing gender categories as it would not be appropriate to make assumptions about what category to include them in.

Estimated pay gap calculation

Because of the significant gaps in the intersectional workforce data submitted to the Commission, it was not possible to calculate accurate pay gaps using the exact salaries of employees in defined entities. Instead, a measure for estimated pay gaps was developed by assigning base salaries in the workforce data (i.e., actual salaries recorded in payroll systems) to the People matter survey base salary ranges selected by diverse respondents. Respondents to the People matter survey in 2021 were able to select their yearly income from salary brackets increasing in $10,000 increments. These ranged from ‘Less than $45,000’, followed by ‘$45,000-$54,999’, through to ‘$175,000-$184,999’ and finally ‘$185,000 or more’. Respondents were also given the option to select ‘Prefer not to say’.

To get a more accurate understanding of pay in particular organisations, median base salaries within every salary range were calculated for each defined entity and each industry group (so the mid-point of all reported salaries for that organisation or industry within each pay bracket). This median was taken from the workforce data for all employees (regardless of gender and other attributes). These median base salaries for each organisation and in each $10,000 bracket available in the People matter survey were then assigned to each respondent to the survey.

The median base salaries assigned to individual respondents to the survey were then used to calculate an overall median for each specific group that was reported on (e.g. ‘Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Women’ or ‘Men with disabilities’). This median for a particular cohort was then used to calculate an approximate pay gap between two specific groups.

These pay gaps are not calculated on the actual salaries of the individuals in each group and are therefore estimated only.

Funded research Grants

In addition to the 2021 workplace gender audit data and the People matter survey, insights in this report are also drawn from research funded under the Commission’s Research Grants Round 2022. This round of funding was focussed on contextualising and deepening the Commission’s understanding of the inaugural audit data, primarily by applying an intersectional lens. Studies funded under the scheme were required to collect qualitative data to complement the quantitative audit data, and examine how experiences of gender inequality are shaped or compounded by other forms of discrimination or disadvantage.

The following 5 projects received funding:

- ‘Make Us Count: Understanding Aboriginal Women’s Experiences in Victorian Public Sector Workplaces’ – Associate Professor Debbie Bargallie, Griffith University

- ‘Caring and Workplace Gender Equality in the Public Sector in Victoria’ – Associate Professor Alysia Blackham, The University of Melbourne with the Australian Discrimination Law Experts Group

- ‘Getting on at Work: Progression and Promotion of Women with Disability in the Victorian Public Service’ – Dr Jannine Williams, Queensland University of Technology with the Disability Leadership Institute and the Victorian Public Service Enablers Network

- ‘Victorian Local Councils and Gender Equality: Examining Commitments to Diversity and the Experiences of Women from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds’ – Dr Hyein (Ellen) Cho, Monash University

- ‘Rurality and Workforce Participation: Exploring Prevalence of Part-time and Insecure Work in Grampians Public Sector Roles’ – Dr Cathy Tischler, Federation University with Women’s Health Grampians, ByFive and the Wimmera Development Association

In relation to the first 4 projects listed above, the research findings are principally discussed in chapters one, two, three and four respectively. The final project examining rural experiences in the public sector does not relate directly to a specific chapter in this report (or a specific intersectional attribute listed in the Act). Instead, insights from this important project are presented in a ‘special look’ section of this report.

Language, lived experience perspectives and gender-inclusivity

Preferred language and terminology used to identify and describe marginalised groups of people is constantly evolving. In this report, the Commission seeks to centre the voices of people with lived experience of discrimination. As such, wherever possible, the report adopts the preferred terminology of marginalised groups, while acknowledging that these conversations are far from settled.

Another way the Commission seeks to centre the voices of marginalised groups is through ensuring diverse perspectives contributed to this report. The funded research grants included in this report were led by academics with lived experience of the intersecting forms of inequality their grant examined, and participants in the studies had lived experiences of intersecting inequalities in public sector workplaces. In addition to this, the Commission invited lived-experience experts and other specialists to review the report in part or whole. These reviewers included:

- Claire Mumme and Nick Logan. Victorian Public Sector Commission

- Diana K. Piantedosi. Director of Policy, Advocacy and Community Engagement at Women with Disabilities Victoria

- Maria Watson-Trudgett. First Nations Consultant

- Yasmin Poole. Master in Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Graduate, University of Oxford

- The VPS Women of Colour Network (WoCN) also provided several reviews and input, which were taken into consideration where possible when finalising the report.

The Commission would like to thank our research partners and participants, generous reviewers, and employees in our defined entities – especially those who work to drive gender equality for everyone in their organisations. While the Commission is thankful for these contributions, responsibility for the final version of this report rests with the Commission.

Lastly, there is very little workforce data and research in relation to gender-diverse Australians. This group also may not feel safe to disclose their gender in official contexts, including the workplace. As such, much of this report discusses gender in binary terms, reflecting the available data across both the broader research landscape, as well as within the Commission’s own data collection. The Commission expects that the Act will drive improved data collection and quality in Victoria to reflect the gender diversity that exists in our society. Changes in research and data collection are essential to make gender-diverse cohorts visible.

Structure of the report

In the Baseline report, the Commission used the 7 gender equality indicators under the Act to organise individual chapters. While this approach was extremely useful in the context of reporting on gender disaggregated data, it is less so in the context of intersectional data. All the groups highlighted here experience multiple forms of structural disadvantage, which tend to result in worse outcomes in relation to the indicators.

To best highlight intersectional experiences, this report offers 5 chapters investigating how the intersection of gender and one other attribute shape discrimination and disadvantage in public sector workplaces. These are:

- Gender and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander employees

- Gender and employees of different ages

- Gender and employees with disabilities

- Gender and culturally and racially marginalised employees

- Gender and LGBTIQ+ employees.

The chapters are presented in the same order as each of these attributes in the Act. Each chapter begins by offering background information on the status of the group in Australian society, followed by a short literature review of key workplace issues impacting that group, with a focus on how these are gendered. This is followed by intersectional data analysis about the cohort, drawn from the Commission’s 2021 workplace gender audit, as well as an overview of findings drawn from the Commission’s Research Grants Round 2022. The Commission acknowledges that these chapters do not represent a comprehensive view of intersecting forms of discrimination in Victorian public sector workplaces. Rather, the 5 chapters reflect the data collected by the Commission about groups that experience systemic forms of disadvantage.

As discussed above, in the 2021 workplace gender audit, only a small proportion of defined entities returned reliable workforce data in relation to intersectional attributes. As such, the final ‘Recommendations’ chapter offers insights into tangible ways that defined entities can improve their approach to collecting data about marginalised groups, with a particular focus on privacy and ensuring employees feel safe to disclose sensitive information about themselves.

Chapter 1: Gender and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Employees

This chapter looks at the intersectional data in relation to gender and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander employees

This report uses a variety of terminology when referring to Australia’s First Peoples. Blanket terms favoured by governments such as ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ or ‘Indigenous’ are unable to account for the diversity that comprises the hundreds of Nations and language groups residing across this continent. While some peoples prefer to be acknowledged by their particular group or clan name, others prefer the term ‘First Nations’ (Diversity Council Australia 2021:9). With respect to continuing (cultural) diversity, this report proceeds by following in the footsteps of the authors of the Commission’s funded research project (Bargallie et al. 2023), as well as the recent Gari Yala (Speak the Truth) report. Here, the Commission uses ‘Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples’ or ‘First Nations peoples’ interchangeably with ‘Indigenous’ for brevity. The phrase Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander is used throughout this report to include individuals who are both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, as well as one or the other. When the term ‘Indigenous’ is used, where applicable, the Commission writes ‘Indigenous peoples’ to foreground and draw attention to existing diversity. The Commission acknowledges that issues of terminology and naming are contentious and apologises for any inadvertent offence caused.

Indigenous Australians represent the oldest living continuous cultures in the world, comprise approximately 3.8% of the total population and are dispersed across hundreds of Nations and language groups (AIHW 2023a). Yet, First Nations peoples in Australia experience systemic forms of discrimination and disadvantage. Significant gaps remain between Indigenous Australians’ and non-Indigenous Australians’ outcomes across several key indicators such as wealth, income, employment, educational attainment and wellbeing (AHRC 2020:48). The systemic inequalities that First Nations peoples experience today are shaped by the historical and ongoing impacts of colonisation and dispossession.

Prior to colonisation in 1788, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had well-developed systems of work and governance. These systems were severely disrupted by the arrival of British colonisers (Evans 2021:8), who stole First Nations people’s land and exploited their labour. Large numbers of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples—including children—were removed from their families and communities and forced to work on missions, settlements, reserves and stations (Kidd 2000). Significant abuse and exploitation were often gendered, with Indigenous women and girls subjected to forced menial and domestic labour, and physical and sexual abuse (Bargallie et al. 2023:16). Indigenous men and boys were more commonly used for unpaid pastoral work and physical labour (Bargallie 2020:50).

Since colonisation, First Nations peoples have continued to be disadvantaged when it comes to paid work. These disadvantages have stemmed from interlinked and systemic legal and cultural inequalities, including laws that discount or punish traditional cultural practices and Indigenous ways of knowing (Bargallie 2020:50-51), and racist stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as lazy and incapable of governing their own lives (Bargallie 2023). The Challenging Racism Project 2015-16 found that First Nations peoples experience one of the highest levels of everyday racism in Australia (25% higher than for non-Indigenous people) (Blair et al. 2017:10). Half of First Nations peoples experience discrimination in the workplace (50.4%), as compared to only a third of non-Indigenous people (32.4%). First Nations peoples have always engaged in various forms of solidarity and resistance to both structural and everyday racism. Nonetheless, the impacts of colonialism continue to produce multiple social, cultural, geographic and economic factors that negatively impact upon First Nations Australians’ lives today (Australian Government 2020). Racism in broader Australian government policies, particularly the White Australia policy, is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4: Gender and culturally and racially marginalised employees.

This chapter explores the intersection of discrimination against First Nations peoples and people of different genders in the workplace. However, there is very little workplace data and research in relation to Australians who are both Indigenous and gender diverse. The Commission expects that the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) will drive improved data collection and quality in Victoria to reflect the gender diversity that exists in our society and make gender-diverse cohorts visible. In this chapter, the Commission acknowledges this lack of data on trans and gender-diverse people has meant that issues are generally only able to be analysed and discussed for women and men.

Key workplace issues for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples

Between 2008 and 2018, the Closing the Gap target to halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people was not met in any Australian state or territory (Australian Government 2020). An increased emphasis on caring responsibilities within First Nations communities, in combination with poorer health outcomes overall (including a reduced life expectancy and higher rates of mental illness), higher rates of children in out-of-home care, and higher rates of incarceration and exposure to violence, create barriers to accessing employment (Bargallie et al. 2023:16; Australian Government 2020;). Indigenous Australians continue to be, on average, less likely to be employed, are paid less, and are less likely to be in leadership roles than non-Indigenous Australians (WGEA 2023). In 2018, 49.1% of First Nations Australians of working age participated in the workplace in some form. For non-Indigenous Australians, this percentage was 75.9% (Minderoo Foundation 2022:16).

Demand and supply side barriers limit First Nations peoples’ likelihood of securing and retaining jobs (Biddle et al. 2023). On the demand side, workplace discrimination is a common issue reported by First Nations people (VPSC 2023a). For example, the Indigenous Employment Index has found that over half of the Indigenous Australians interviewed reported experiences of direct or indirect racism when at work (Minderoo Foundation 2022:31). Research also directs attention to the negative impacts of daily racial microaggressions, that is, everyday derogatory and hostile behaviours, practices, and processes that First Nations Australians must negotiate in the workplace, but which often remain invisible to non-Indigenous people (Bargallie 2020:103). Geography is another key ‘demand side’ barrier. First Nations peoples living in urban areas are more likely to be employed than those living in non-urban areas (45% compared to 35%) (ABS 2016). On the supply side, Biddle et al. (2023) note health and education outcomes and caring responsibilities as key workforce participation barriers.

Issues of retention and career advancement are also common among First Nations peoples in Australian workplaces, including in the public sector. Recent analysis by the Victorian Public Sector Commission (2023b) found that in 2022, 1.2% of Victorian Public Service (VPS) employees identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and of these, most were paid at the less senior VPS grades four (16.7%) and five (23.7%). The numbers of First Nations peoples employed at higher levels reduces significantly, with 9.5% of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander staff employed at VPS grade six, 0.4% at the level of senior technical specialist, and 3.5% at the executive level. This reduction in representation of First Nations peoples in more senior levels is also visible in the New South Wales Public Service. A 2021 report shows that First Nations peoples are more concentrated in grades 1/2 and 3/4, at 5.3% and 4.8% of total employees at each level (NSW Public Service Commission 2021). At the highest non-executive level, grade 11/12, the percentage drops to 2.2% of the total number of employees (NSW Public Service Commission 2021).

Key workplace issues for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women

Workplace discrimination and barriers to workforce participation

The Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report (2021:3) notes the problems that can arise when researchers make comparisons between men and women within First Nations communities, discussing how this can impose Western values or create an additional divide between members of an already marginalised group. Nonetheless, the report also emphasises that gendered analysis remains crucial in the context of employment outcomes for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women. Not only are First Nations women likely to experience gender discrimination as women, but they are also likely to have unique experiences of inequality as First Nations women.

While there is a lack of research examining First Nations women’s workplace experiences (see Evans 2021:2), information that does exist suggests that they face compounded forms of discrimination and disadvantage due to their gender and their Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity (Bargallie et al. 2023:12).

In the contemporary context, First Nations men are more likely to be employed than First Nations women in the 15-64 age group (37.9% compared with 18.4%) (AIHW 2021). Indigenous women are half as likely as Indigenous men to own or manage a business, they are overrepresented in lower weekly income brackets and underrepresented in the highest brackets, and they are less likely to be supported in the workplace if they encounter racism or experience culturally unsafe situations (Evans 2021:1; WGEA 2023).

Cultural load and unpaid labour

Cultural load is the extra, often invisible, workload attached to Indigenous employees. This includes, but is not limited to, requests or expectations to educate non-Indigenous colleagues about the histories and practices of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, reviewing culturally sensitive material, caring responsibilities, attending ‘Sorry Business’, living and working on Country, racism, tokenism and lateral violence (VPSC 2023a). The Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report identified gender-based inequalities in relation to this additional work:

- Indigenous women experience the highest burden of this unpaid labour, reflecting research that shows non-Indigenous women are more likely to be asked to undertake undervalued work assignments which do little to advance their careers (Evans 2021:7).

- Indigenous women in management roles have a higher cultural load than those in lower levels (Evans 2021:1).

- Men in management often work in organisations with higher levels of support, where they can work more effectively as agents of change (Evans 2021, p.1).

- Indigenous women who are also carers have the highest cultural load (Evans 2021:9).

While this work is often important and may be personally fulfilling, it is frequently overlooked by managers and can also impede career progression (Evans 2021: 5, 8).

Inadequate support in culturally unsafe workplace settings

The Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report (Evans 2021:6) draws attention to the lack of organisational support available to Indigenous women who are already working in culturally unsafe workplaces. The report notes that unfair treatment and harassment based on race are experienced by both women and men. However, women are significantly less likely to be able to access adequate support to assist them in navigating these negative experiences.

High rates of gendered violence

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women experience high rates of violence and sexual harassment both within and outside the workplace. These forms of violence stem from a complex array of drivers including gender inequality and the ongoing impacts of colonialism and racism (Our Watch, 2018). In the workplace context, the Australian Human Rights Council found that 59% of First Nations women and 53% of First Nations men reported being sexually harassed at work in the last 5 years (2022:53).

More broadly, Indigenous women experience violence at 3.1 times the rate of non-Indigenous women, and they are 11 times more likely to die from assault (Our Watch 2018:6). This violence is often misunderstood as an ‘Indigenous’ problem, however, men from all cultural backgrounds commit violence against Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women (Our Watch 2018:5). While the disproportionate levels of violence against First Nations women are a significant concern in and of themselves, they are also a workplace issue. It is well documented that forms of violence such as family violence have significant impacts on access to paid employment, career development and lifetime earnings (Weatherall and Gavin 2021; Wibberley et al. 2018).

Extensive caring responsibilities

Workplace support available to carers is often gendered, with research demonstrating that women with caring responsibilities are more often seen as a liability, whereas men with caring responsibilities can be seen as a strength (Weeden et al. 2016). This lack of support is compounded for Indigenous women, with the Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report (2021:9) pointing to Indigenous mothers and carers as a particularly marginalised group. First Nations women are more likely to care for children, family, and community members than First Nations men and non-Indigenous people, having one of the highest levels of caring responsibilities in Australia (Evans 2021:9). Research shows that this cohort of women are more likely to work in culturally unsafe workplaces and receive low levels of organisational support when they experience racism (Evans 2021:9). It is possible that Indigenous women carers prioritise income stability above seeking out culturally safe workplaces, however further research is required to better understand the discrimination experienced by this group (Evans 2021:9).

Commissioned research

In 2022-23, the Commission engaged Associate Professor Debbie Bargallie, Professor Bronwyn Carlson and Madi Day to examine the experiences of First Nations women working in the Victorian public sector. Participation in Bargallie et al.’s research project was open to any First Nations women working in the Victorian public sector. However, the researchers only received responses from Aboriginal women. As such, the Commission uses the term ‘Aboriginal women’ when directly reporting on this project.

The researchers undertook 25 online and face-to-face Yarning sessions with Aboriginal women employed in Victorian public sector organisations. They also conducted an online survey, with a total of 10 respondents. The research team used Indigenous research approaches to investigate how Aboriginal women experienced working in the Victorian public sector. Further details of the research method can be found at the research project Make us Count: Understanding Aboriginal women's experiences in Victorian public sector workplaces.

Key findings

Barriers to recruitment

Participants identified significant recruitment and promotion barriers for Aboriginal women in the Victorian public sector. These included inflexible recruitment processes, low pay offerings and a focus on recruitment of Aboriginal peoples into junior roles. Some participants raised geographical limitations, noting that most job opportunities were concentrated in Melbourne, or large regional centres, and that there was a lack of flexibility offered to support Aboriginal people to continue to live regionally or rurally. Participants also raised challenges related to power in hiring decisions, with dominant Aboriginal families often represented on recruitment panels, causing potential conflicts of interest. Some felt that these barriers to entry showed that government commitments to hiring more Aboriginal peoples were not genuine.

Barriers to career progression

A variety of barriers to career progression were identified. Participants noted that senior level management positions went mostly to Aboriginal men, and that Aboriginal women were less able to progress beyond entry or lower-level positions, despite being qualified. Some participants felt that they were being held back because they performed well at their job and contributed to workplace diversity, so their employer didn’t want to lose them. Some said that hiring Aboriginal people felt tokenistic. This was compounded by a lack of visible Aboriginal women in leadership positions.

Precarious employment and unpaid labour

Aboriginal women reported challenges in securing consistent employment, leading to feelings of stress, frustration, and depression. The issue of unpaid labour emerged prominently, with expectations to engage in tasks beyond their designated roles, particularly related to Aboriginal matters. Some believed their long-term work prospects could be adversely affected if they didn't comply.

Racisms at work

Participants reported experiencing racism related to the ways things are set up (structural level), in the policies and rules (systemic level), and in how people treat them (interpersonal level). Racism was reported to show up in daily interactions with non-Indigenous people that are harmful (racial microaggressions), such as comments about Aboriginal culture, stereotyping, or not respecting ideas from Aboriginal peoples. Participants often felt that their non-Indigenous colleagues held racist expectations about how Aboriginal peoples should look or behave. These expectations manifested in negative behaviours towards Aboriginal peoples, making it difficult for participants to comfortably be themselves at work. Participants also reported experiencing discrimination from other Aboriginal peoples in the workplace, because of internalised racism.

The failure of complaint policies, processes, and practices

A common theme among participants was a lack of justice in their experiences of reporting workplace discrimination and sexual harassment. Some participants explained that they chose not to make a complaint, due to a lack of trust in reporting processes. Others did make a formal complaint but found that they did not receive appropriate support. Some participants reported that they had been pressured to stay quiet by managers or forced to quit their jobs because of bullying or harassment incidents.

Experiences of abuse and harassment were reportedly compounded by poor organisational processes and responses. These included a lack of support from leaders, an unwillingness to intervene in conflict between multiple Aboriginal peoples, inappropriate responses from managers or People and Culture departments, poor reporting processes and a focus on individual behaviour rather than on workplace policies, processes and practices. In all, participants felt that these compounding challenges made them the problem, rather than the incident they were reporting, causing them to be re-victimised in the process of attempting to address harm.

CGEPS audit data: Key insights

This section reports on insights from the Commission’s 2021 workplace gender audit workforce data and the 2021 People matter survey (PMS). Workforce data is data drawn from organisations’ human resources and payroll systems. The People matter survey is an anonymous survey completed by approximately 90% of organisations with reporting obligations under the Act.

First Nations employees in the 2021 workplace gender audit

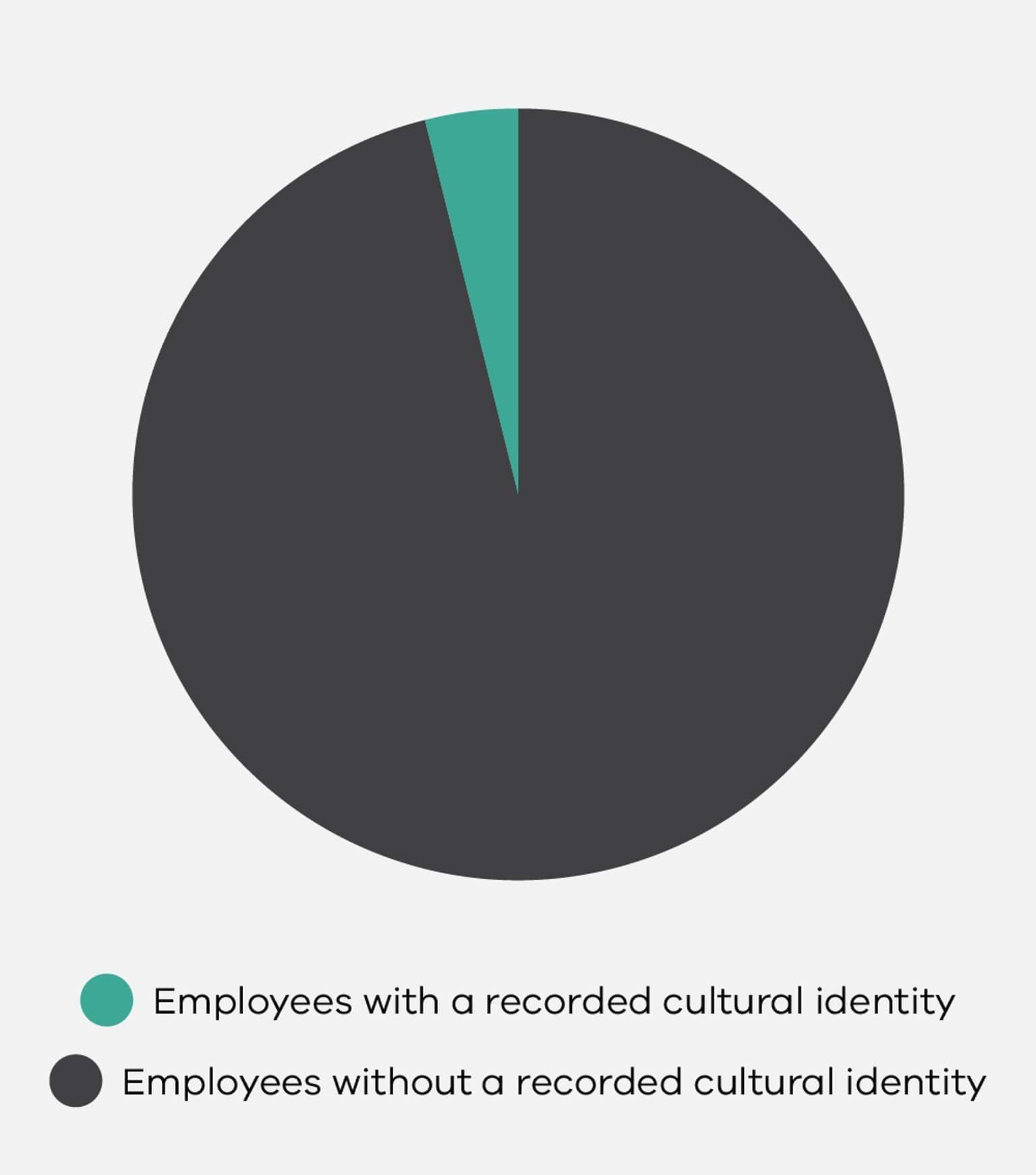

For the 2021 workforce data, only a small number of organisations were able to provide reliable data regarding the First Nations status of their employees.

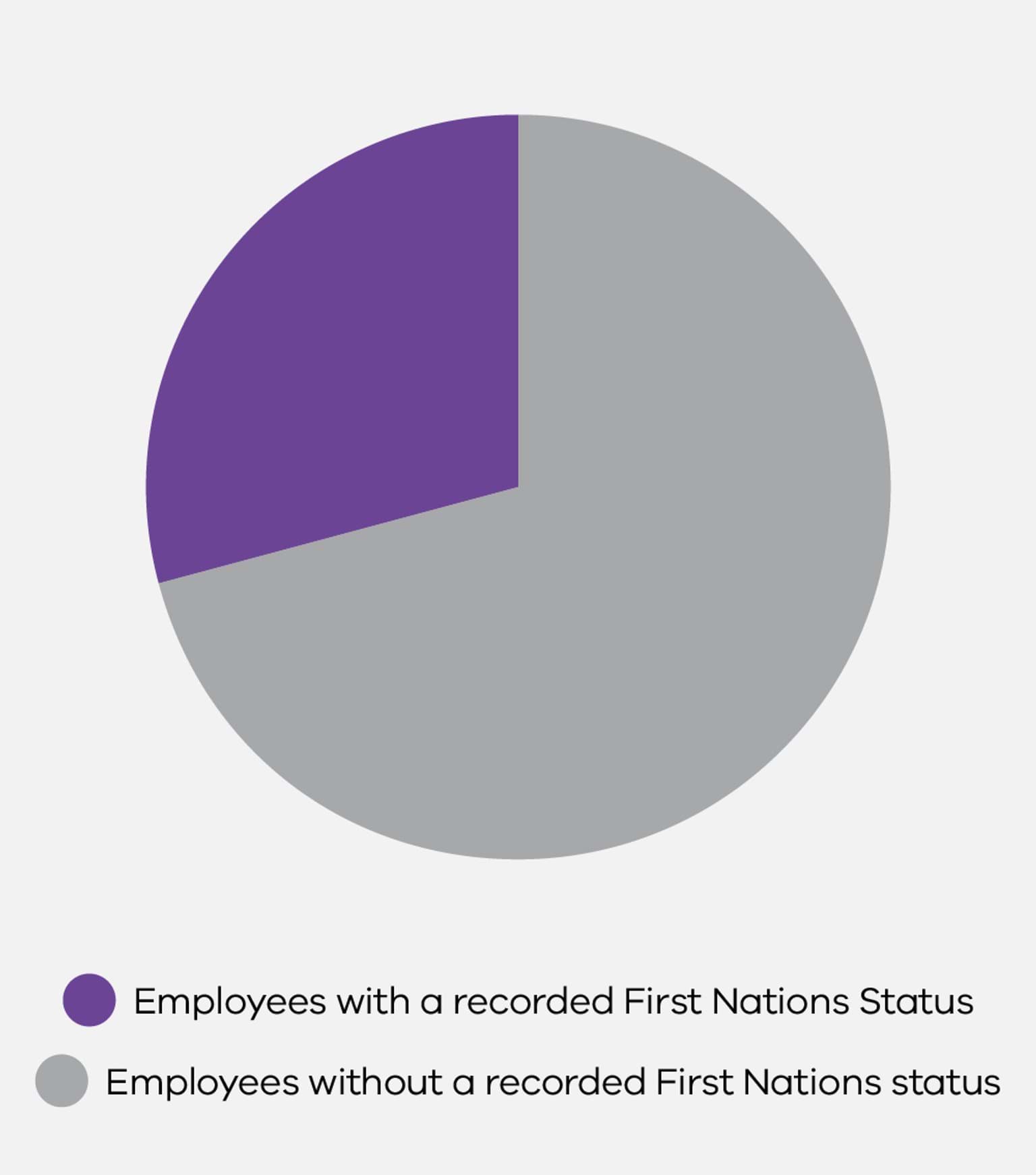

Figure 1.1 illustrates that across all organisations with reporting obligations in the 2021 workplace gender audit, 71% of employees did not have a recorded First Nations status. This means that more than 7 in 10 employees covered by the 2021 workforce data either had no First Nations status recorded or worked for organisations that did not collect and store information about First Nations status through their workforce systems at all.

Such a low reporting rate makes it very difficult to draw conclusions from this workforce data and impacts the generalisability of the findings across the sector. As a result, the remainder of the data presented in this section is derived from the 2021 People matter survey.

People matter survey respondents who identified as First Nations peoples made up 1% of the total workforce.

This broadly aligns with the 1% of the Victorian population who identified as First Nations people in the 2021 Census (ABS 2022a). Approximately 0.97% of women and 1.3% of men responding to the survey were First Nations peoples.

Gender composition at all levels of the workforce

First Nations women had the lowest representation in manager positions.

As Table 1.1 demonstrates, First Nations women were less likely to report holding positions as senior managers (overseeing lower-level managers) or supervisors (managing employees who are not managers themselves) than Indigenous men and non-Indigenous men and women. Non-Indigenous men reported the highest rates of supervisor and senior manager roles of any cohort.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting senior manager roles | PMS Respondents reporting supervisor roles |

| Indigenous women | 6% | 11% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 7% | 15% |

| Indigenous men | 9% | 17% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 13% | 20% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

First Nations women were slightly less likely to work part time than non-Indigenous women.

As set out in Table 1.2 below, First Nations women were slightly less likely than non-Indigenous women to report working part time. However, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women were nearly four-times as likely to work part time than their male counterparts.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting part-time work |

| Indigenous women | 39% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 44% |

| Indigenous men | 10% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 12% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

It is not known whether the lower rates of part-time work for both First Nations women and men compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts is related to lower access to part-time work. However, the larger rates of part-time work for both groups of women, and the smaller rates for both groups of men, suggest that part-time work continues to be closely associated with gendered norms related to both paid and unpaid labour.

Gender pay equity

First Nations women were overrepresented in lower income brackets and underrepresented in higher income brackets.

Almost 60% of First Nations women reported earning under $95,000 as their full-time base salary, compared to only 38% of non-Indigenous men. Respondents to the People matter survey 2021, from which this data is drawn, were able to select their yearly income from salary brackets increasing in $10,000 increments. These ranged from ‘Less than $45,000’, followed by ‘$45,000-$54,999’, through to ‘$175,000-$184,999’ and finally ‘$185,000 or more’. Respondents were also given the option to select ‘Prefer not to say’. Table 1.3 shows these salary options rolled up into $30,000 groupings.

The average annual full-time salary in Australia, based on the ABS full-time weekly earnings in November 2021, was approximately $91,000 (ABS 2022b). While the options provided to respondents in the People matter survey do not allow analysis of salaries above or below $91,000 specifically, Table 1.3 shows that First Nations women were more likely than men (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and non-Indigenous women to report a full-time equivalent salary of less than $95,000.

Salary Range | Indigenous women | Non-Indigenous women | Indigenous men | Non-Indigenous men |

| Less than $65,000 | 30% | 22% | 18% | 10% |

| $65,00 – 94,999 | 29% | 32% | 35% | 28% |

| $95,000 –$124,000 | 21% | 22% | 23% | 28% |

| $125,000 –$154,999 | 3% | 5% | 7% | 11% |

| $155,000 –$184,999 | 1% | 2% | 1% | 5% |

| Over $185,000 | 1% | 2% | 2% | 5% |

| Prefer not to say | 9% | 10% | 9% | 9% |

| Unanswered | 5% | 5% | 4% | 4% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Income disparity at the upper end of the pay scale shows the compounding impact of inequality on the basis of Indigenous status and gender. Non-Indigenous men were more than 4 times as likely to report higher incomes than First Nations women (over $125,000), with First Nations men and non-Indigenous women approximately twice as likely to report salaries in these brackets.

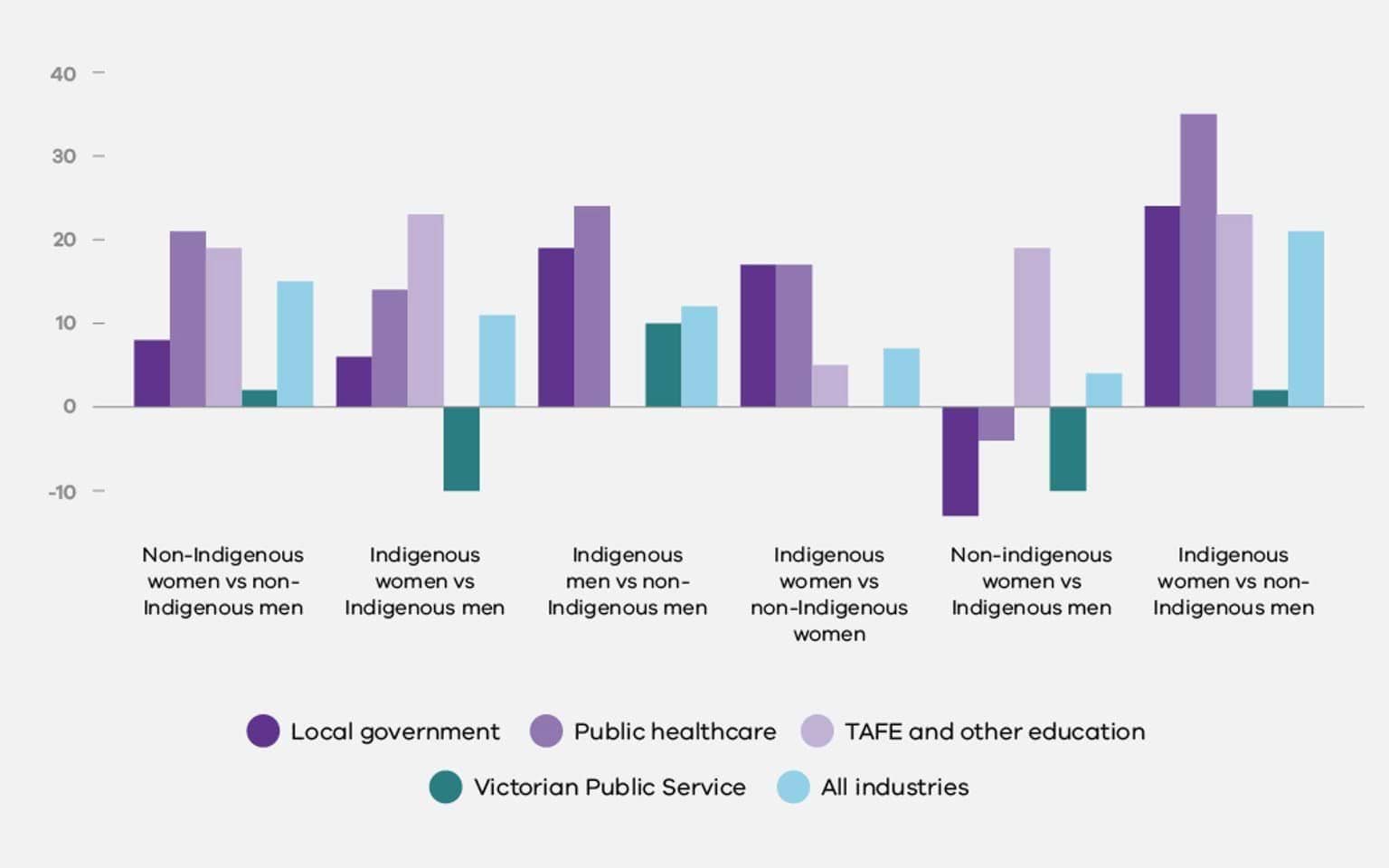

Estimated industry pay gaps were generally largest between First Nations women and non-Indigenous men.

As set out in Table 1.4, across 3 of the 4 industry groups with sufficient data and at the all-industries level, estimated pay gaps were largest between First Nations women and non-Indigenous men. At the all-industries level, the pay gap between these two groups was 21%.

In the Public healthcare industry, the pay gap between First Nations women and non-Indigenous men was the greatest at 35%. The Victorian Public Service industry bucked this trend, with the smallest gap between these groups, at 2%. Notably, First Nations men experienced a significantly larger pay gap than First Nations women when compared to non-Indigenous men in this industry group, and the pay gap between Indigenous women and men was 10% in favour of women.

| Industry | Local government | Public healthcare | TAFE and other education | Victorian Public Service | All industries |

| Non-Indigenous women vs non-Indigenous men | 8% | 21% | 19% | 2% | 15% |

| Indigenous women vs Indigenous men | 6% | 14% | 23% | -10% | 11% |

| Indigenous men vs non-Indigenous men | 19% | 24% | 0% | 10% | 12% |

| Indigenous women vs non-Indigenous women | 17% | 17% | 5% | 0% | 7% |

| Non-indigenous women vs Indigenous men | -13% | -4% | 19% | -10% | 4% |

| Indigenous women vs non-Indigenous men | 24% | 35% | 23% | 2% | 21% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The pay gaps presented here are estimates, produced using a combination of salary bracket data from the People matter survey, outlined above, and the Commission’s workforce remuneration data. This is because the workforce data is not comprehensive enough to produce reliable pay gap calculations based on actual salaries. Please see the Introduction to this report for further detail on the approach taken.

Workplace sexual harassment and discrimination

First Nations women reported experiencing sexual harassment at similar rates to non-Indigenous women.

As Table 1.5 shows, 6.5% of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women reported having experienced sexual harassment at work in the previous 12 months. First Nations men were more likely than their non-Indigenous counterparts to report having experienced sexual harassment.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting sexual harassment |

| Indigenous women | 6.5% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 6.5% |

| Indigenous men | 5.4% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 3.5% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women were more likely to report experiences of sexual harassment than men, while Indigenous men were more likely than non-Indigenous men to report experiences of sexual harassment.

The two most common types of sexual harassment reported, regardless of gender or Indigenous status, were ‘Intrusive questions about my private life or comments about my physical appearance’ and ‘Sexually suggestive comments or jokes that made me feel offended’.

Please note that the People matter survey 2021 was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was when many people were working from home (except for essential workers, such as healthcare workers). This means that there might have been a potential decrease in certain types of sexual harassment between workers. However, it remains unclear how much the COVID-19 pandemic impacted these numbers.

First Nations people reported experiencing discrimination at higher rates than their non-Indigenous colleagues.

Regardless of gender, First Nations peoples were approximately twice as likely to say they had experienced discrimination in the preceding 12 months as non-Indigenous respondents. Table 1.6 shows these differences in experiences of discrimination.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting discrimination |

| Indigenous women | 10% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 5% |

| Indigenous men | 11% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 5% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The most common type of discrimination reported by First Nations men was being denied opportunities for training and professional development. The most common type of discrimination reported by all three other groups in the table above was being denied opportunities for promotion.

However, First Nations women were more likely than any of the other three groups to select ‘Other’ as the reason for the discrimination, indicating that their experience of discrimination was not listed in the available options. As there was no free text option associated with this question, the type of discrimination the women experienced is unknown. Further research is required to understand First Nations women’s experiences of discrimination in public sector organisations.

Recruitment and promotion practices

First Nations peoples and non-Indigenous women and men were roughly equally likely to agree that recruitment and promotion decisions in their organisations were fair.

As Table 1.7 shows, both First Nations and non-Indigenous people, regardless of gender, were about as likely to agree with the statement ‘My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit’. First Nations women had the highest level of agreement, at 56%.

Indigenous status and gender | My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit | |

Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| Indigenous women | 56% | 19% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 55% | 17% |

| Indigenous men | 53% | 23% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 53% | 22% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.