Disability theory today remains closely linked to activism and advocacy. As such, preferred terminology and language used to describe persons with disability varies across cultures and is often dependant on the particular social movement context from which it emerged. For example, in some contexts, identity-first language (disabled person) is preferred as it recognises disability as a way of experiencing the world that has social value and is a source of pride (AFDO n.d.). By contrast, person-first language (person with disabilities) reduces the focus on impairment and centres personhood to counteract the history of dehumanisation experienced by people with disabilities (AFDO n.d.). In this report, the Commission follows the advice of People with Disability Australia (2021) (the national disability rights and advocacy organisation) and uses the term ‘people with disabilities’ or ‘people with disability’ to reflect the preferred terminology in an Australian context.

In 2018, there were 4.4 million Australians living with disability, which equates to 17.7% of the total population (ABS 2019). Available data points to consistently low rates of workforce participation for people with disability. Just over half of working-age people with disability are currently in the workforce (53%), compared with 84% of people without disability (AIHW 2022a:311). Despite disability civil rights movements and protective legislative frameworks, significant barriers to workforce participation persist and people with disability remain underemployed in Australia. When people with disabilities do find employment, it is often characterised by low pay, insufficient hours, and segregated workplaces (Henriques-Gomes 2022; Meltzer et al. 2020)

People with disability face high levels of workplace discrimination and stigma from both their employer and their colleagues (ABS 2019). Discrimination also varies according to disability type. For example, people with sensory or speech difficulty have the highest employment rate in Australia (50%), while people with psychosocial disability, including nervous or emotional conditions, mental illness, and/or behavioural problems, are least likely to be employed (26%) (AIHW 2022a:321). The compounding of gender-based and disability-based discrimination also results in labour market outcomes that are significantly lower for women with disability than men with disability. Women with disability are also one of the poorest groups overall in Australian society (WWDA 2020).

Understandings of disability in Australia have evolved to increasingly centre the voices of people with disability and highlight social barriers to equality. Recent research and advocacy efforts led by people with disability adopt a human rights approach. This approach to disability highlights the importance of upholding the rights of people with disabilities to ensure they have the means of support to fully participate and be fully included in all aspects of life and society and to live a flourishing and dignified life (DARU 2019). It also emphasises that it is society and ableist assumptions that create barriers for people with a disability (DARU 2019)

There is very little workforce data and research in relation to gender-diverse Australians with disability. The Commission expects that the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) will drive improved data collection and quality in Victoria to reflect the gender diversity that exists in our society and make gender-diverse cohorts visible. In this chapter, the Commission acknowledges this lack of data on trans and gender-diverse people has meant that issues are generally only able to be analysed and discussed for women and men.

Key workplace issues for people with disabilities

Under international law, Australia has an obligation to ensure people with disabilities can rightfully, comfortably and freely work. Despite this, Australians with disabilities face intersecting and systemic barriers to employment (WWDA 2020; AHRC 2016). This reduces their opportunities for economic participation and consequently reduces professional growth, earning capacity, job security and overall wealth compared to people without disabilities (AHRC 2016).

Employment issues faced by people with disabilities are varied, but include:

- Challenges looking for, finding and keeping a job (Devine et al. 2021; Meltzer et al., 2020; Stafford et al. 2017)

- Discrimination due to barriers in the work environment such as accessibility and inflexible hours and settings (Darcy et al. 2016; Devine et al. 2021; O’Meara 2023)

- Poor experiences in other areas of life that impact employment (Devine et al. 2020; Disability Royal Commission 2020)

- Lower pay – sometimes less than minimum wage (Disability Royal Commission 2020; Donelly et al. 2020)

- Low levels of job preparedness (Haber et al. 2016; Stafford et al. 2017)

- Stigma and discrimination by managers and/or co-workers (Meltzer et al. 2020; Murfitt et al. 2018)

- Entrenched, long-term unemployment (Devine et al. 2020; Moore 2021).

Addressing structural barriers and the systemic discrimination against people with disability poses unique challenges for governments, policymakers and activists worldwide (Beaupert et al. 2017). In Australia, employers are obligated to provide ‘reasonable adjustments or accommodations’ for employees with disabilities, and failure to do so can amount to discrimination (AHRC 2016). Experiences of, and barriers to, employment and job retention vary significantly depending on the type of disability a person has. The Disability Discrimination Act 1992 contains 6 categories of disability types including learning, intellectual, physical, psychiatric, sensory, or neurological disability. However, the sheer variety of associated experiences highlight the limitations of workplace ‘one-size-fits-all’ disability policy. Instead, focusing on what the person needs to comfortably do their job as well as providing personalised reasonable adjustments increases inclusivity with benefits to the person, the organisation and society (Raymond et al. 2019).

Direct and indirect discrimination

A 2022 report from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found that 1 in 6 Australians with disability reported experiencing disability discrimination over a 12-month period (AIHW 2022a:11). Such discrimination can be ‘direct’ or ‘indirect’.

- Direct discrimination is when someone is treated less favourably because of their protected attribute, such as not hiring someone because of their disability.

- Indirect discrimination is when a condition or requirement has the effect of discriminating against someone because of their protected attribute, such as requiring all workers to attend a presentation but not providing Auslan interpreting or closed captions for Deaf or hard of hearing employees.

Both types of discrimination are unlawful under the Discrimination Act 2006 (Cth).

The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) (2022) reported that in 2021-22 disability discrimination was the most common ground for complaint. Of complaints in the area of employment, 22% were related to disability.

Physical or mental disability is a protected attribute under the Fair Work Act 2009. See https://www.fairwork.gov.au/employment-conditions/protections-at-work/protection-from-discrimination-at-work for further detail.

Key workplace issues for women with disabilities

Low labour force participation

In 2018, labour force participation was higher among men with disability than women with disability (ABS 2019). Specifically:

- 56.1% of men with disability compared with 50.7% of women with disability participated in the labour force

- 31.0% of men with a profound or severe limitation compared with 23.6% of women with a profound or severe limitation participated in the labour force (ABS 2019).

Gender-neutral workplace needs assessments

Across legislative, policy, and service contexts, people living with disability in Australia are often treated as if they have no sex or gender (Frohmader 2014; O’Shea and Frawley 2019; WWDA 2020). Yet women with disability have different life experiences compared to men with disability, largely due to systemic inequality between men and women (WWDA 2020).

Gender neutral analyses of the needs of people with disability in the workforce can therefore perpetuate existing gender-based discrimination. Gender neutral approaches can also produce inaccurate framings of the problems faced by women and girls with disability, resulting in policies that fail to account for their specific needs and experiences (WWDA 2020).

Higher rates of gendered violence, sexual harassment and sexual assault

Research has found that women with disability experience higher rates of gendered violence both within and outside of the workplace. For example:

- Women with disability are more likely to experience family violence and sexual assault (Victorian Government 2016)

- 62% of women with disability under 50 have experienced violence since the age of 15 (Dowse et al., 2016)

- Women with disabilities experience 3 times the rate of sexual violence as women without disabilities (Dowse et.al. 2016)

- People with disability are more likely than those without disability to have been sexually harassed in the workplace in the last 5 years (48% and 32% respectively) (AHRC 2022c:53)

- Women with disability are more likely than men with disability to have been sexually harassed in the workplace in the last 5 years (54% and 38% respectively) (AHRC 2022c53).

Despite the concerning picture painted by the statistics above and research that describes violence against women and girls with disabilities in Australia as endemic, the problem is also largely invisible (Dowse et al. 2016). Due to poor data collection practices at a government level, as well as documented ‘cover up’ practices at an institutional level, violence against women and girls with disability is chronically underreported (Dowse et al. 2016; WWDA 2020).

While the high rate of violence against women with disability is a significant human rights issue, it is also a workplace issue. Research shows that violence against women, including women with disabilities, has significant impacts on access to paid employment, career development and lifetime earnings (Frohmader et al. 2015; Healy et al. 2008; Weatherall and Gavin 2021; Wibberley et al. 2018).

Lack of workplace flexibility

Women with disability face compounded discrimination in the workplace due to a lack of flexible work options. Caring is a traditionally gendered phenomenon, and women with disabilities undertake particularly high levels of caring (Dangar et al. 2023). Adding to the need to access flexibility to support gendered caring responsibilities, women with disability also face disability-specific challenges. These may include health needs and transportation barriers, which can make it difficult for people with disability to work a standard full-time work week. Research has shown that the majority of people who are unemployed, retired, are carers, have a disability, or have a long-term illness, would be inclined to start working if suitable flexible work were available (Victorian Government 2016). This demonstrates the serious barrier that rigid and inflexible work creates for people with disability, and women with disability in particular.

Challenges in accessing support

Gendered norms and assumptions around the division of domestic labour and caring responsibilities mean that women with disabilities are often more time-poor than men with disabilities. Women with disabilities also frequently carry a greater administrative load than men with disabilities (Yates et al. 2022). For example, women are often expected to manage the disabilities of their male partners and children, with 35% of primary carers who are women also having a disability themselves (Yates et al. 2022:4).

In addition, men are more likely to be diagnosed with disabilities that are easier to access funding for. While men and women are diagnosed with disability at similar rates, women are underdiagnosed with some conditions, such as autism spectrum disorders (Yates et al. 2021). They are also more likely to be diagnosed with conditions like arthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome, which are painful and socially disabling, but are difficult to get government support for (Yates et al. 2021).

Commissioned research

In 2022-23, the Commission engaged Dr Jannine Williams, Ms Maria Khan and Professor Robyn Mayes to examine the experiences of people that identify as women with disability in the Victorian Public Service (VPS). Williams and her colleagues (2023), in collaboration with the VPS Enablers Network and the Disability Leadership Institute, undertook 49 qualitative interviews with women with disability employed in the VPS. They also analysed quantitative data extracts from the People matter survey (PMS) 2021 (106,069 people were included in this survey).

The research looked at what helped women with disability (enablers) and what made it hard for them (barriers) to move up in their careers. Aiming to advise VPS employers on how they can best support women with disability to achieve their career goals, the research centres the voices of women with disability and utilises a collaborative co-design approach to project design and analysis. Further details of the research method and co-design approach can be found in the research project Getting on at work: Progression and promotion of women with disability in the Victorian public service.

Key findings

Sharing information about disability and requesting reasonable adjustments

Sharing disability information and requesting reasonable adjustments can bring advantages and challenges. Participants reported that sharing disability information can result in getting reasonable workplace adjustments, feeling more confident at work, and can help co-workers to better understand disability inclusion. Obtaining workplace adjustments is important for career progression, as it enables a person to demonstrate their capabilities and talent.

However, some women reported challenges. These included feeling uncomfortable with telling others about their disability, for fear of stigma and discrimination, or finding the lack of process for requesting reasonable adjustments demoralising and frustrating. Participants also identified burdensome approval processes and policies as a deterrent.

The challenges of self-advocacy

Self-advocacy was viewed as both a pathway to inclusion and a burden. Participants noted that self-advocacy was particularly challenging when their needs were not being met and it became a necessity. Some participants noted that the burden of advocacy is even heavier for women who also have caregiving duties. Other research has also highlighted how disability self-advocacy is a highly gendered process (Yates et al. 2021). Often, women who stand up for themselves, including women with disabilities, are perceived more negatively than women who advocate for others (Wade 2001). This demonstrates how gendered norms can harm both the career progression and well-being of women with disabilities in the workplace.

The importance of managers and teams

Participants identified supportive teams and managers as crucial for psychological well-being and enabling them to fully engage at work. However, they can also reduce career mobility. Some participants feared that the support they currently receive is unique and would be difficult to find elsewhere. Experiencing or even hearing about unsafe environments can create fear about the unpredictability of new team dynamics for women with disabilities. Some participants faced challenges with hostile managers or psychologically unsafe teams, limiting their advancement and success. In particular, participants reported that conscious and unconscious bias from managers or colleagues often led to them being overlooked for advancement.

Visibility and mentorship

Having visible leaders with disability is important for inspiring women with disability in their careers and signalling inclusive organisational values. However, participants reported a lack of people with acknowledged and/or visible disabilities in leadership roles across the VPS. Potential reasons suggested for this included the rigid and ableist expectations of senior roles and potential repercussions for senior leaders who are open about their disability status. Participants also reported that colleagues without disability are more readily assumed to be able to grow and develop in a leadership role, while they needed to demonstrate higher levels of competence to be considered in the first place.

Formal and informal mentors were identified as important to help build confidence, provide advice, and illuminate paths to progression. Barriers reported by participants to accessing mentorship included difficulties in balancing a mentoring relationship with their daily workload, lack of information on how to participate in mentoring relationships, and a scarcity of mentors with knowledge of intersecting forms of inequality.

Systemic change is vital

Policies and practices in the VPS were seen to be improving. Participants highlighted how policies such as remote and flexible working practices, disability-identified roles in recruitment, and opportunities to submit expressions of interest for secondments and ‘acting up’ duties can support inclusion. Universal flexible work arrangements, like remote work, were seen as especially important for supporting health needs and caregiving responsibilities, promoting self-confidence, enabling work-life balance, and helping women with disability to navigate commuting challenges. However, access to these policies was heavily reliant on individual managers. Inconsistent policy application was a significant cause of stress and created burdens on individual women to negotiate with their managers.

CGEPS audit data: Key insights

This section reports on insights from the Commission’s 2021 workplace gender audit workforce data and the 2021 People matter survey (PMS). Workforce data is data drawn from organisations’ human resources and payroll systems. The People matter survey is an anonymous survey completed by approximately 90% of organisations with reporting obligations under the Act.

Employees with disability in the 2021 workplace gender audit

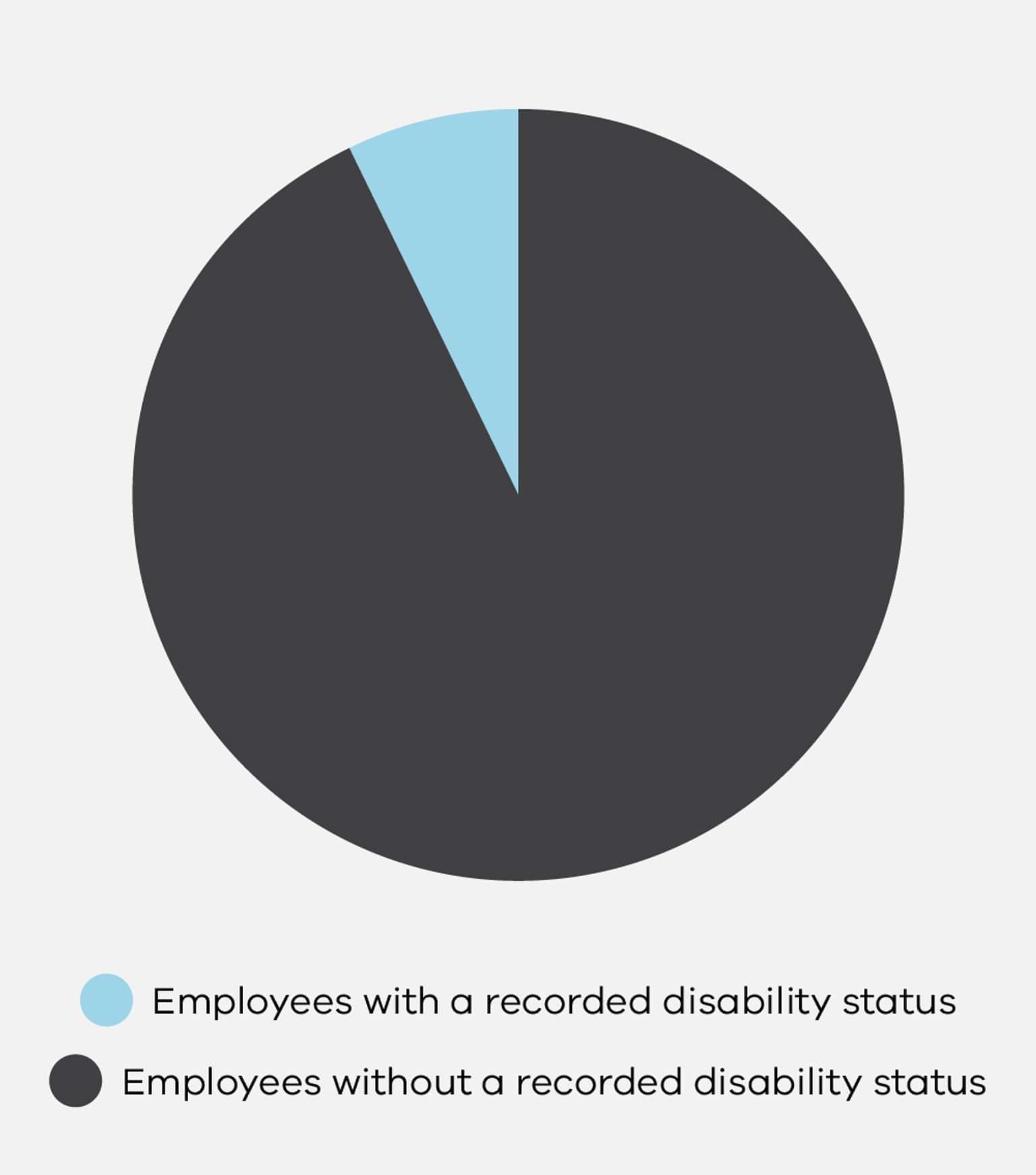

For the 2021 workforce data, only a small proportion of organisations were able to provide reliable data regarding the disability status of their employees.

Only 28% of defined entities included any data related to disability status in their workforce reporting, and this data was not always comprehensive for all employees. Figure 3.1 illustrates that across all organisations with reporting obligations in the 2021 workplace gender audit, only 6% of employees had a recorded disability status. The remaining 94% of employees covered by the 2021 workforce data either had no disability status recorded, or worked for organisations that did not collect and store information about disability status through their workforce systems at all. Among those employees who did have a disability status recorded, only 1% (500 employees) identified as a person with disability.

Such a low reporting rate makes it very difficult to draw conclusions from this workforce data and impacts the generalisability of the findings across the sector. As a result, the remainder of the data presented in this section is derived from the 2021 People matter survey.

Respondents to the People matter survey who identified as having a disability made up 5% of the total workforce, with men and women equally represented in this percentage.

While the survey response rates were higher than the workforce data, the low number of respondents identifying with disability meant that responses were too low to generate reliable results in some analyses, such as at the industry level.

Gender composition at all levels of the workforce

Women with disabilities were underrepresented in managerial roles.

As Table 3.1 highlights, men without disabilities were far more likely to hold positions as senior managers (overseeing lower-level managers) and supervisors (managing employees who are not managers themselves) than men with disabilities, and women regardless of disability status.

| Disability status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting senior manager roles | PMS Respondents reporting supervisor roles |

| Women with disabilities | 5% | 12% |

| Women without disabilities | 7% | 15% |

| Men with disabilities | 9% | 15% |

| Men without disabilities | 13% | 20% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Women with disabilities reported the lowest rates of supervisor and senior manager roles of any cohort in the table above.

Women with disabilities and women without disabilities had an equal likelihood of working part-time, with both at 44%.

As shown in Table 3.2 below, women were more than twice as likely to work in part-time roles compared to men, regardless of whether they had a disability. 21% of men with disabilities worked part-time, whereas the percentage was lower, at 12%, for men without disabilities.

| Disability status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting part-time work |

| Women with disabilities | 44% |

| Women without disabilities | 44% |

| Men with disabilities | 21% |

| Men without disabilities | 12% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Gender pay equity

Women with disabilities were overrepresented in lower income brackets and underrepresented in higher income brackets.

Women with disabilities were more likely than men (with or without disabilities) or women without disabilities to report full-time base salaries under $95,000. Respondents to the People matter survey 2021, from which this data is drawn, were able to select their yearly income from salary brackets increasing in $10,000 increments. These ranged from ‘Less than $45,000’, followed by ‘$45,000-$54,999’, through to ‘$175,000-$184,999’ and finally ‘$185,000 or more’. Respondents were also given the option to select ‘Prefer not to say’. Table 3.3 shows these salary options rolled up into $30,000 groupings.

The average annual full-time salary in Australia, based on the ABS full-time weekly earnings in November 2021, was approximately $91,000 (ABS 2022b). While the options provided to respondents in the People matter survey do not allow analysis of salaries above or below $91,000 specifically, Table 3.3 demonstrates that women with disabilities were more likely than men (with or without disabilities) and women without disabilities to report a full-time equivalent salary of less than $95,000.

| Salary Range | Women with disabilities | Women without disabilities | Men with disabilities | Men without disabilities |

| Less than $65,000 | 26% | 22% | 17% | 10% |

| $65,00 – 94,999 | 32% | 32% | 32% | 28% |

| $95,000 –$124,000 | 20% | 22% | 24% | 28% |

| $125,000 –$154,999 | 4% | 5% | 8% | 11% |

| $155,000 –$184,999 | 2% | 2% | 3% | 5% |

| Over $185,000 | 1% | 2% | 2% | 6% |

| Prefer not to say | 9% | 10% | 10% | 9% |

| Unanswered | 6% | 5% | 5% | 3% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Income disparity at the upper end of the pay scale shows the compounding impact of inequality on the basis of disability status and gender. Men without disabilities were more than 3 times as likely to report incomes over $125,000 when compared to women with disabilities. Men with disabilities were still almost twice as likely to report incomes over $125,000 than women with disabilities.

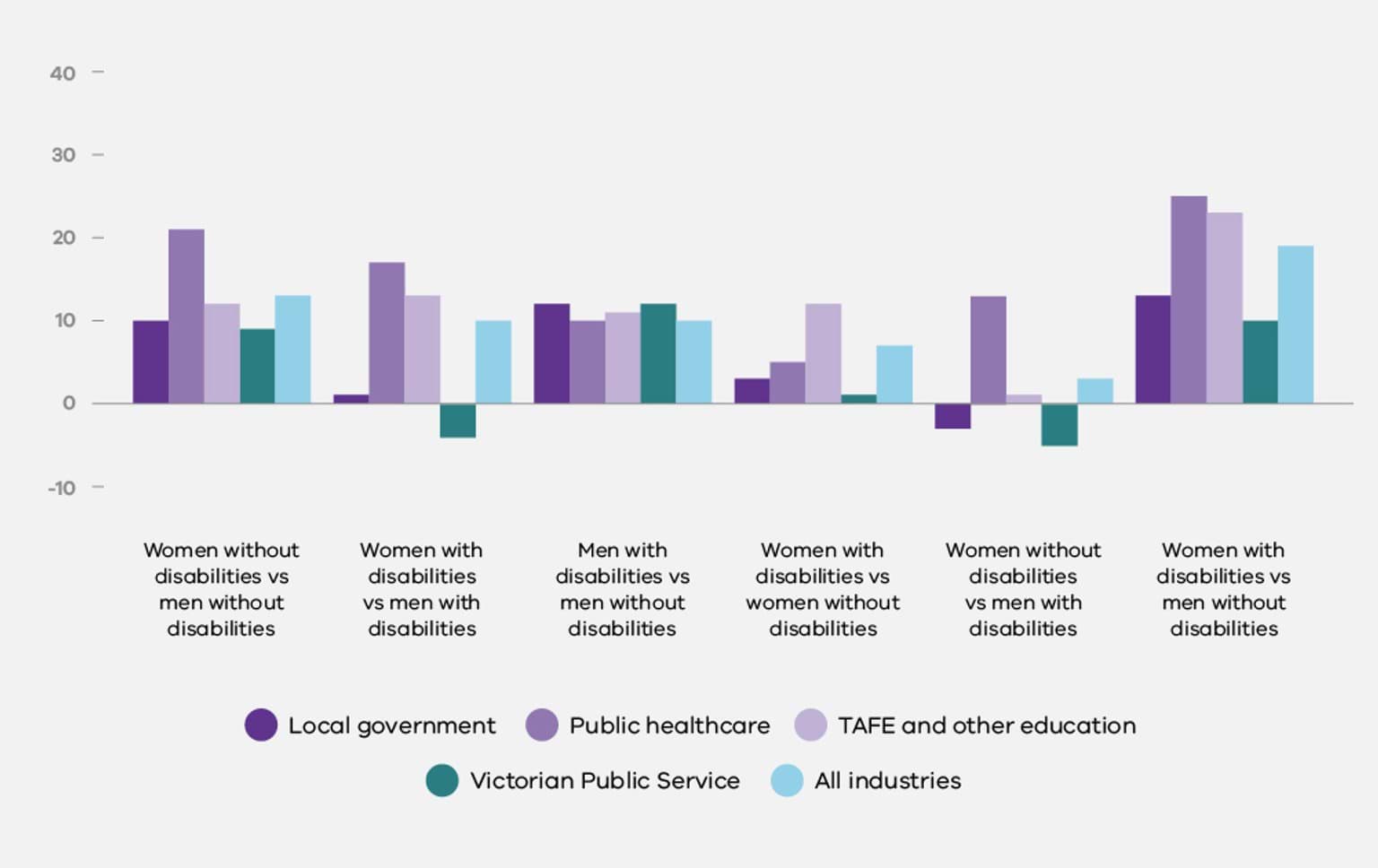

Estimated industry pay gaps were generally largest between women with disabilities and men without disabilities.

As set out in Table 3.4, across 3 of the 4 industry groups with sufficient data and at the all-industry level, estimated pay gaps were largest between women with disabilities and men without disabilities. At the all-industries level, the pay gap between these two groups was 19%.

In the Public healthcare sector, this gap was largest at 25%. In the Victorian Public Service men with disabilities experienced a larger pay gap (13%) than women with disabilities (10%), when compared to men without disabilities.

In all industries except the Victorian public service, there was a pay gap between women with disabilities and men with disabilities in favour of men (1-17%).

The pay gaps presented here are estimates, produced using a combination of salary bracket data from the People matter survey, outlined above, and the Commission’s workforce remuneration data. This is because the workforce data is not comprehensive enough to produce reliable pay gap calculations based on actual salaries. Please see the Introduction to this report for further detail on the approach taken.

| Industry | Local government | Public healthcare | TAFE and other education | Victorian Public Service | All industries |

| Women without disabilities vs men without disabilities | 10% | 21% | 12% | 9% | 13% |

| Women with disabilities vs men with disabilities | 1% | 17% | 13% | -4% | 10% |

| Men with disabilities vs men without disabilities | 12% | 10% | 11% | 13% | 10% |

| Women with disabilities vs women without disabilities | 3% | 5% | 12% | 1% | 7% |

| Women without disabilities vs men with disabilities | -3% | 13% | 1% | -5% | 3% |

| Women with disabilities vs men without disabilities | 13% | 25% | 23% | 10% | 19% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The lower salaries reported by men with disabilities align with international research suggesting the salaries of men with disabilities may be suppressed, due to the fact disabilities can conflict with traditional norms of masculinity (Pettinicchio and Maroto 2017). This is an example of where harmful gender norms can also disadvantage men.

Workplace sexual harassment and discrimination

Women with disabilities experiences higher rates of sexual harassment at work.

Both women and men with disabilities reported experiencing higher rates of sexual harassment than those without disabilities. Table 3.5 demonstrates the percentage of respondents to the People matter survey who said they had experienced sexual harassment in the last 12 months.

Table 3.5. Percentage of People matter survey respondents reporting they experienced sexual harassment in the last 12 months, by disability status and gender.

| Disability status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting sexual harassment |

| Women with disabilities | 12% |

| Women without disabilities | 6% |

| Men with disabilities | 8% |

| Men without disabilities | 3% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Women with disabilities reported experiencing sexual harassment at twice the rate of women without disabilities, and 4 times the rate of men without disabilities.

Women with and without disabilities reported ‘Sexually suggestive comments or jokes that made me feel offended’ as the most common form of sexual harassment experienced with ‘Intrusive questions about my private life or comments about my physical appearance’ the second most common. In men with and without disabilities the same most common experiences were reported, but in reverse order.

The People matter survey 2021 was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was when many people were working from home (except for essential workers, such as healthcare workers). This means that there might have been a potential decrease in certain types of sexual harassment between workers. However, it remains unclear how much the COVID-19 pandemic impacted these numbers.

Individuals with disabilities experienced higher rates of discrimination.

Regardless of gender, employees with disabilities were approximately three times as likely to say they had experienced discrimination compared to their colleagues without disabilities. Table 3.6 shows these differences in experiences of discrimination.

| Disability status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting discrimination |

| Women with disabilities | 14% |

| Women without disabilities | 5% |

| Men with disabilities | 15% |

| Men without disabilities | 5% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The most common type of discrimination reported by women with disabilities was being denied flexible work arrangements or other adjustments. In contrast, men with disabilities, along with women and men without disabilities, most commonly reported being denied opportunities for promotion.

Given access to workplace flexibility and other reasonable adjustments is a key enabler for people with disabilities, this form of discrimination reported by women is concerning.

Recruitment and promotion practices

People with disabilities were less likely to agree that recruitment and promotion decisions in their organisations were fair.

As Table 3.7 shows, both women and men with disabilities were less likely to agree with the statement ‘My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit’ than people without disabilities.

| Disability status and gender | My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit | |

| Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| Women with disabilities | 46% | 25% |

| Women without disabilities | 55% | 16% |

| Men with disabilities | 43% | 28% |

| Men without disabilities | 53% | 22% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

People with disabilities were less likely to feel that they had an equal chance at promotion in their organisations.

As Table 3.8 shows, people with disabilities were less likely to agree, and more likely to disagree with the statement ‘I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation’.

| Disability status and gender | I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation | |

| Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| Women with disabilities | 34% | 37% |

| Women without disabilities | 47% | 24% |

| Men with disabilities | 35% | 38% |

| Men without disabilities | 47% | 26% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

Flexible work practices

Women with disabilities were more likely than women without disabilities, and men regardless of disability, to report working flexibly.

Both women and men with disabilities reported higher levels of flexible working arrangements than those of the same gender without disabilities. However, women with disabilities were the most likely of any of these groups to report working flexibly. Table 3.9 illustrates the proportion of respondents in each group who reported using flexible work.

| Disability status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting flexible work |

| Women with disabilities | 39% |

| Women without disabilities | 30% |

| Men with disabilities | 31% |

| Men without disabilities | 22% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Women, regardless of disability status, most often reported using flexible start and finish times. Men, regardless of disability status, most often reported working part time.

Discussion and conclusions

Consistent with previous research, this chapter highlights the significant structural barriers faced by women with disability in workplace contexts. The Commission’s data analysis demonstrates that women with disability are underrepresented in senior roles and overrepresented in below-average full time salary brackets. Furthermore, women with disability disproportionately experience sexual harassment in Victorian public sector workplaces. These findings highlight that there is a still a long way to go to achieve the meaningful inclusion of women with disability in the Victorian public sector.

The Commission’s workplace gender audit data and the funded research project led by Dr Williams and colleagues demonstrate the importance of improved data collection about people of different genders with disability. Data is required to better understand how ableism and gender inequality combine to produce specific workplace inequalities. The lack of workforce data on disability status, and thus the need to rely on survey data that is not linked to employee records, meant that this analysis was unable to explore the access to training and other professional development and promotional opportunities, as well as occupational and industrial segregation of people with disabilities in Victorian public sector organisations. The Commission also had to estimate pay gaps rather than being able to rely on precise salary data.

The findings in this chapter reinforce the importance of systemic change to drive workplace equality for women with disability. In particular, consistency in the support that organisations provide to women with disability can reduce the barriers to their full participation. Ensuring inclusive environments and access to consistent support means that women with disability do not choose to limit their career progression in order to remain with a supportive manager or in a supportive team (Williams et al., 2023). It also reduces the need for women to advocate for themselves. This is important, not only because disability self-advocacy can take time, effort and an emotional toll, but also because women and gender-diverse people with disability who self-advocate are often viewed through harmful gender stereotypes as ‘pushy’ or ‘difficult’ (Williams et al. 2023).

Developing organisation-wide support and inclusion involves moving towards a culture of respect and trust. Important gains can be made by focussing on the role of middle-management, building psychological safety for women with disability, and evaluating relevant policies and their implementation (Williams et al., 2023). Shifting the responsibility from individuals with disability to organisations can be achieved by encouraging middle-management to proactively initiate career progression conversations with women with disability and raise awareness around available sources of support, such as leadership and mentoring programs (Williams et al. 2023). Openly acknowledging gender inequality and ableism in the workplace, while celebrating women with disability as assets to an organisation rather than burdens, can encourage respectful communications and an inclusive culture (Williams et al. 2023). Including women with disability in policy design and review and standardising remote and flexible working options can ensure policies are fit-for-purpose, do not unintentionally discriminate and do not fall to individuals to negotiate (Williams et al. 2023).

Lastly, while this chapter draws attention to the interactions between gender and disability in a workplace setting, there is still work to do to improve data collection and knowledge about people of self-described gender with disability. Research from Williams and her colleagues (2023, p. 15) found that participants who identified as non-binary or ‘other’ gender identities were more likely to report having a disability than women or men. In addition, non-binary people with disability encountered greater challenges related to workplace culture than women or men with disability (Williams et al., 2023, p.4). These findings highlight that further research about this cohort is required.

Updated