This report uses a variety of terminology when referring to Australia’s First Peoples. Blanket terms favoured by governments such as ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ or ‘Indigenous’ are unable to account for the diversity that comprises the hundreds of Nations and language groups residing across this continent. While some peoples prefer to be acknowledged by their particular group or clan name, others prefer the term ‘First Nations’ (Diversity Council Australia 2021:9). With respect to continuing (cultural) diversity, this report proceeds by following in the footsteps of the authors of the Commission’s funded research project (Bargallie et al. 2023), as well as the recent Gari Yala (Speak the Truth) report. Here, the Commission uses ‘Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples’ or ‘First Nations peoples’ interchangeably with ‘Indigenous’ for brevity. The phrase Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander is used throughout this report to include individuals who are both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, as well as one or the other. When the term ‘Indigenous’ is used, where applicable, the Commission writes ‘Indigenous peoples’ to foreground and draw attention to existing diversity. The Commission acknowledges that issues of terminology and naming are contentious and apologises for any inadvertent offence caused.

Indigenous Australians represent the oldest living continuous cultures in the world, comprise approximately 3.8% of the total population and are dispersed across hundreds of Nations and language groups (AIHW 2023a). Yet, First Nations peoples in Australia experience systemic forms of discrimination and disadvantage. Significant gaps remain between Indigenous Australians’ and non-Indigenous Australians’ outcomes across several key indicators such as wealth, income, employment, educational attainment and wellbeing (AHRC 2020:48). The systemic inequalities that First Nations peoples experience today are shaped by the historical and ongoing impacts of colonisation and dispossession.

Prior to colonisation in 1788, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had well-developed systems of work and governance. These systems were severely disrupted by the arrival of British colonisers (Evans 2021:8), who stole First Nations people’s land and exploited their labour. Large numbers of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples—including children—were removed from their families and communities and forced to work on missions, settlements, reserves and stations (Kidd 2000). Significant abuse and exploitation were often gendered, with Indigenous women and girls subjected to forced menial and domestic labour, and physical and sexual abuse (Bargallie et al. 2023:16). Indigenous men and boys were more commonly used for unpaid pastoral work and physical labour (Bargallie 2020:50).

Since colonisation, First Nations peoples have continued to be disadvantaged when it comes to paid work. These disadvantages have stemmed from interlinked and systemic legal and cultural inequalities, including laws that discount or punish traditional cultural practices and Indigenous ways of knowing (Bargallie 2020:50-51), and racist stereotypes of Indigenous peoples as lazy and incapable of governing their own lives (Bargallie 2023). The Challenging Racism Project 2015-16 found that First Nations peoples experience one of the highest levels of everyday racism in Australia (25% higher than for non-Indigenous people) (Blair et al. 2017:10). Half of First Nations peoples experience discrimination in the workplace (50.4%), as compared to only a third of non-Indigenous people (32.4%). First Nations peoples have always engaged in various forms of solidarity and resistance to both structural and everyday racism. Nonetheless, the impacts of colonialism continue to produce multiple social, cultural, geographic and economic factors that negatively impact upon First Nations Australians’ lives today (Australian Government 2020). Racism in broader Australian government policies, particularly the White Australia policy, is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4: Gender and culturally and racially marginalised employees.

This chapter explores the intersection of discrimination against First Nations peoples and people of different genders in the workplace. However, there is very little workplace data and research in relation to Australians who are both Indigenous and gender diverse. The Commission expects that the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) will drive improved data collection and quality in Victoria to reflect the gender diversity that exists in our society and make gender-diverse cohorts visible. In this chapter, the Commission acknowledges this lack of data on trans and gender-diverse people has meant that issues are generally only able to be analysed and discussed for women and men.

Key workplace issues for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples

Between 2008 and 2018, the Closing the Gap target to halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people was not met in any Australian state or territory (Australian Government 2020). An increased emphasis on caring responsibilities within First Nations communities, in combination with poorer health outcomes overall (including a reduced life expectancy and higher rates of mental illness), higher rates of children in out-of-home care, and higher rates of incarceration and exposure to violence, create barriers to accessing employment (Bargallie et al. 2023:16; Australian Government 2020;). Indigenous Australians continue to be, on average, less likely to be employed, are paid less, and are less likely to be in leadership roles than non-Indigenous Australians (WGEA 2023). In 2018, 49.1% of First Nations Australians of working age participated in the workplace in some form. For non-Indigenous Australians, this percentage was 75.9% (Minderoo Foundation 2022:16).

Demand and supply side barriers limit First Nations peoples’ likelihood of securing and retaining jobs (Biddle et al. 2023). On the demand side, workplace discrimination is a common issue reported by First Nations people (VPSC 2023a). For example, the Indigenous Employment Index has found that over half of the Indigenous Australians interviewed reported experiences of direct or indirect racism when at work (Minderoo Foundation 2022:31). Research also directs attention to the negative impacts of daily racial microaggressions, that is, everyday derogatory and hostile behaviours, practices, and processes that First Nations Australians must negotiate in the workplace, but which often remain invisible to non-Indigenous people (Bargallie 2020:103). Geography is another key ‘demand side’ barrier. First Nations peoples living in urban areas are more likely to be employed than those living in non-urban areas (45% compared to 35%) (ABS 2016). On the supply side, Biddle et al. (2023) note health and education outcomes and caring responsibilities as key workforce participation barriers.

Issues of retention and career advancement are also common among First Nations peoples in Australian workplaces, including in the public sector. Recent analysis by the Victorian Public Sector Commission (2023b) found that in 2022, 1.2% of Victorian Public Service (VPS) employees identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and of these, most were paid at the less senior VPS grades four (16.7%) and five (23.7%). The numbers of First Nations peoples employed at higher levels reduces significantly, with 9.5% of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander staff employed at VPS grade six, 0.4% at the level of senior technical specialist, and 3.5% at the executive level. This reduction in representation of First Nations peoples in more senior levels is also visible in the New South Wales Public Service. A 2021 report shows that First Nations peoples are more concentrated in grades 1/2 and 3/4, at 5.3% and 4.8% of total employees at each level (NSW Public Service Commission 2021). At the highest non-executive level, grade 11/12, the percentage drops to 2.2% of the total number of employees (NSW Public Service Commission 2021).

Key workplace issues for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women

Workplace discrimination and barriers to workforce participation

The Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report (2021:3) notes the problems that can arise when researchers make comparisons between men and women within First Nations communities, discussing how this can impose Western values or create an additional divide between members of an already marginalised group. Nonetheless, the report also emphasises that gendered analysis remains crucial in the context of employment outcomes for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women. Not only are First Nations women likely to experience gender discrimination as women, but they are also likely to have unique experiences of inequality as First Nations women.

While there is a lack of research examining First Nations women’s workplace experiences (see Evans 2021:2), information that does exist suggests that they face compounded forms of discrimination and disadvantage due to their gender and their Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander identity (Bargallie et al. 2023:12).

In the contemporary context, First Nations men are more likely to be employed than First Nations women in the 15-64 age group (37.9% compared with 18.4%) (AIHW 2021). Indigenous women are half as likely as Indigenous men to own or manage a business, they are overrepresented in lower weekly income brackets and underrepresented in the highest brackets, and they are less likely to be supported in the workplace if they encounter racism or experience culturally unsafe situations (Evans 2021:1; WGEA 2023).

Cultural load and unpaid labour

Cultural load is the extra, often invisible, workload attached to Indigenous employees. This includes, but is not limited to, requests or expectations to educate non-Indigenous colleagues about the histories and practices of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, reviewing culturally sensitive material, caring responsibilities, attending ‘Sorry Business’, living and working on Country, racism, tokenism and lateral violence (VPSC 2023a). The Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report identified gender-based inequalities in relation to this additional work:

- Indigenous women experience the highest burden of this unpaid labour, reflecting research that shows non-Indigenous women are more likely to be asked to undertake undervalued work assignments which do little to advance their careers (Evans 2021:7).

- Indigenous women in management roles have a higher cultural load than those in lower levels (Evans 2021:1).

- Men in management often work in organisations with higher levels of support, where they can work more effectively as agents of change (Evans 2021, p.1).

- Indigenous women who are also carers have the highest cultural load (Evans 2021:9).

While this work is often important and may be personally fulfilling, it is frequently overlooked by managers and can also impede career progression (Evans 2021: 5, 8).

Inadequate support in culturally unsafe workplace settings

The Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report (Evans 2021:6) draws attention to the lack of organisational support available to Indigenous women who are already working in culturally unsafe workplaces. The report notes that unfair treatment and harassment based on race are experienced by both women and men. However, women are significantly less likely to be able to access adequate support to assist them in navigating these negative experiences.

High rates of gendered violence

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women experience high rates of violence and sexual harassment both within and outside the workplace. These forms of violence stem from a complex array of drivers including gender inequality and the ongoing impacts of colonialism and racism (Our Watch, 2018). In the workplace context, the Australian Human Rights Council found that 59% of First Nations women and 53% of First Nations men reported being sexually harassed at work in the last 5 years (2022:53).

More broadly, Indigenous women experience violence at 3.1 times the rate of non-Indigenous women, and they are 11 times more likely to die from assault (Our Watch 2018:6). This violence is often misunderstood as an ‘Indigenous’ problem, however, men from all cultural backgrounds commit violence against Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women (Our Watch 2018:5). While the disproportionate levels of violence against First Nations women are a significant concern in and of themselves, they are also a workplace issue. It is well documented that forms of violence such as family violence have significant impacts on access to paid employment, career development and lifetime earnings (Weatherall and Gavin 2021; Wibberley et al. 2018).

Extensive caring responsibilities

Workplace support available to carers is often gendered, with research demonstrating that women with caring responsibilities are more often seen as a liability, whereas men with caring responsibilities can be seen as a strength (Weeden et al. 2016). This lack of support is compounded for Indigenous women, with the Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): Gendered Insights report (2021:9) pointing to Indigenous mothers and carers as a particularly marginalised group. First Nations women are more likely to care for children, family, and community members than First Nations men and non-Indigenous people, having one of the highest levels of caring responsibilities in Australia (Evans 2021:9). Research shows that this cohort of women are more likely to work in culturally unsafe workplaces and receive low levels of organisational support when they experience racism (Evans 2021:9). It is possible that Indigenous women carers prioritise income stability above seeking out culturally safe workplaces, however further research is required to better understand the discrimination experienced by this group (Evans 2021:9).

Commissioned research

In 2022-23, the Commission engaged Associate Professor Debbie Bargallie, Professor Bronwyn Carlson and Madi Day to examine the experiences of First Nations women working in the Victorian public sector. Participation in Bargallie et al.’s research project was open to any First Nations women working in the Victorian public sector. However, the researchers only received responses from Aboriginal women. As such, the Commission uses the term ‘Aboriginal women’ when directly reporting on this project.

The researchers undertook 25 online and face-to-face Yarning sessions with Aboriginal women employed in Victorian public sector organisations. They also conducted an online survey, with a total of 10 respondents. The research team used Indigenous research approaches to investigate how Aboriginal women experienced working in the Victorian public sector. Further details of the research method can be found at the research project Make us Count: Understanding Aboriginal women's experiences in Victorian public sector workplaces.

Key findings

Barriers to recruitment

Participants identified significant recruitment and promotion barriers for Aboriginal women in the Victorian public sector. These included inflexible recruitment processes, low pay offerings and a focus on recruitment of Aboriginal peoples into junior roles. Some participants raised geographical limitations, noting that most job opportunities were concentrated in Melbourne, or large regional centres, and that there was a lack of flexibility offered to support Aboriginal people to continue to live regionally or rurally. Participants also raised challenges related to power in hiring decisions, with dominant Aboriginal families often represented on recruitment panels, causing potential conflicts of interest. Some felt that these barriers to entry showed that government commitments to hiring more Aboriginal peoples were not genuine.

Barriers to career progression

A variety of barriers to career progression were identified. Participants noted that senior level management positions went mostly to Aboriginal men, and that Aboriginal women were less able to progress beyond entry or lower-level positions, despite being qualified. Some participants felt that they were being held back because they performed well at their job and contributed to workplace diversity, so their employer didn’t want to lose them. Some said that hiring Aboriginal people felt tokenistic. This was compounded by a lack of visible Aboriginal women in leadership positions.

Precarious employment and unpaid labour

Aboriginal women reported challenges in securing consistent employment, leading to feelings of stress, frustration, and depression. The issue of unpaid labour emerged prominently, with expectations to engage in tasks beyond their designated roles, particularly related to Aboriginal matters. Some believed their long-term work prospects could be adversely affected if they didn't comply.

Racisms at work

Participants reported experiencing racism related to the ways things are set up (structural level), in the policies and rules (systemic level), and in how people treat them (interpersonal level). Racism was reported to show up in daily interactions with non-Indigenous people that are harmful (racial microaggressions), such as comments about Aboriginal culture, stereotyping, or not respecting ideas from Aboriginal peoples. Participants often felt that their non-Indigenous colleagues held racist expectations about how Aboriginal peoples should look or behave. These expectations manifested in negative behaviours towards Aboriginal peoples, making it difficult for participants to comfortably be themselves at work. Participants also reported experiencing discrimination from other Aboriginal peoples in the workplace, because of internalised racism.

The failure of complaint policies, processes, and practices

A common theme among participants was a lack of justice in their experiences of reporting workplace discrimination and sexual harassment. Some participants explained that they chose not to make a complaint, due to a lack of trust in reporting processes. Others did make a formal complaint but found that they did not receive appropriate support. Some participants reported that they had been pressured to stay quiet by managers or forced to quit their jobs because of bullying or harassment incidents.

Experiences of abuse and harassment were reportedly compounded by poor organisational processes and responses. These included a lack of support from leaders, an unwillingness to intervene in conflict between multiple Aboriginal peoples, inappropriate responses from managers or People and Culture departments, poor reporting processes and a focus on individual behaviour rather than on workplace policies, processes and practices. In all, participants felt that these compounding challenges made them the problem, rather than the incident they were reporting, causing them to be re-victimised in the process of attempting to address harm.

CGEPS audit data: Key insights

This section reports on insights from the Commission’s 2021 workplace gender audit workforce data and the 2021 People matter survey (PMS). Workforce data is data drawn from organisations’ human resources and payroll systems. The People matter survey is an anonymous survey completed by approximately 90% of organisations with reporting obligations under the Act.

First Nations employees in the 2021 workplace gender audit

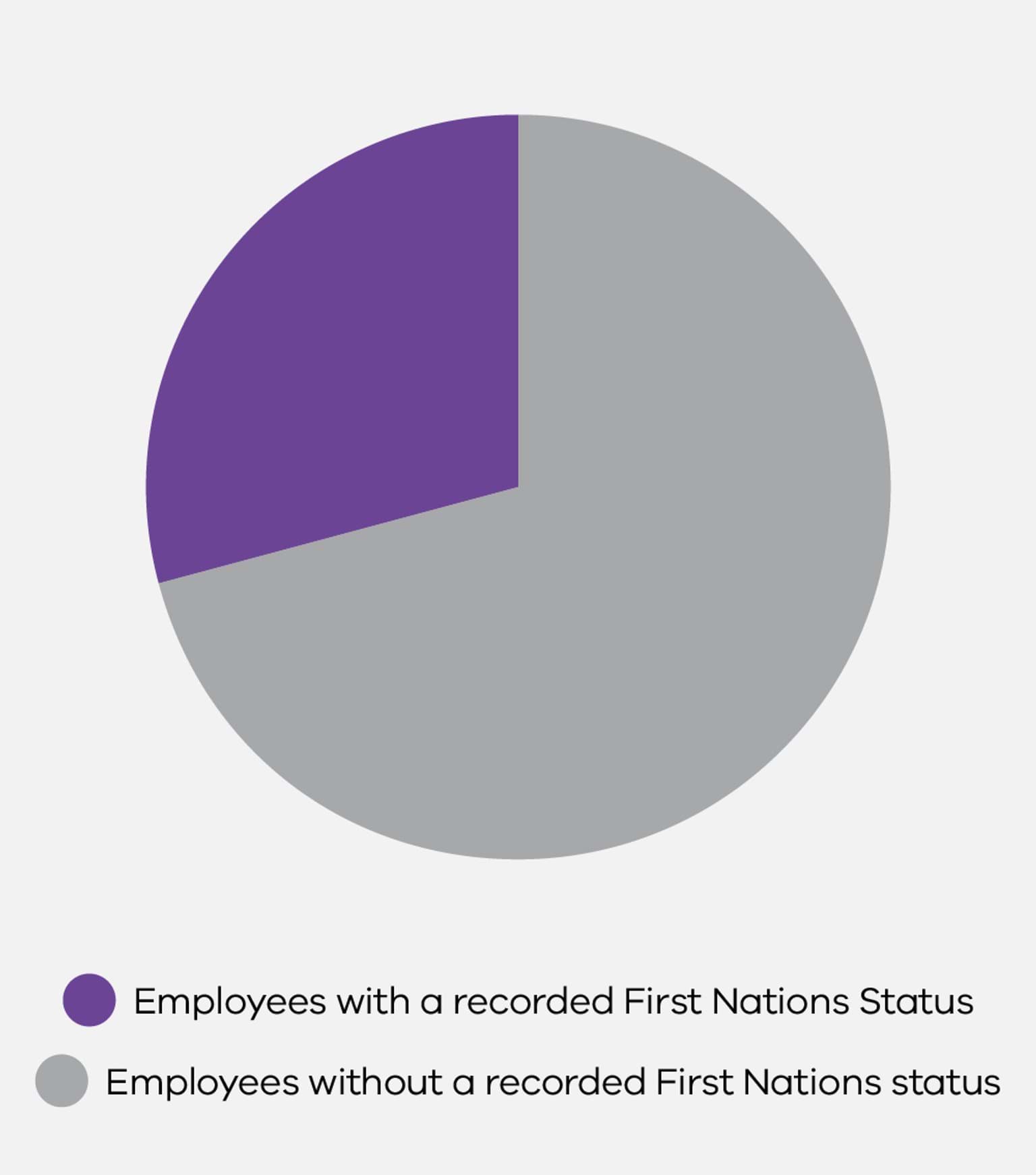

For the 2021 workforce data, only a small number of organisations were able to provide reliable data regarding the First Nations status of their employees.

Figure 1.1 illustrates that across all organisations with reporting obligations in the 2021 workplace gender audit, 71% of employees did not have a recorded First Nations status. This means that more than 7 in 10 employees covered by the 2021 workforce data either had no First Nations status recorded or worked for organisations that did not collect and store information about First Nations status through their workforce systems at all.

Such a low reporting rate makes it very difficult to draw conclusions from this workforce data and impacts the generalisability of the findings across the sector. As a result, the remainder of the data presented in this section is derived from the 2021 People matter survey.

People matter survey respondents who identified as First Nations peoples made up 1% of the total workforce.

This broadly aligns with the 1% of the Victorian population who identified as First Nations people in the 2021 Census (ABS 2022a). Approximately 0.97% of women and 1.3% of men responding to the survey were First Nations peoples.

Gender composition at all levels of the workforce

First Nations women had the lowest representation in manager positions.

As Table 1.1 demonstrates, First Nations women were less likely to report holding positions as senior managers (overseeing lower-level managers) or supervisors (managing employees who are not managers themselves) than Indigenous men and non-Indigenous men and women. Non-Indigenous men reported the highest rates of supervisor and senior manager roles of any cohort.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting senior manager roles | PMS Respondents reporting supervisor roles |

| Indigenous women | 6% | 11% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 7% | 15% |

| Indigenous men | 9% | 17% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 13% | 20% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

First Nations women were slightly less likely to work part time than non-Indigenous women.

As set out in Table 1.2 below, First Nations women were slightly less likely than non-Indigenous women to report working part time. However, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women were nearly four-times as likely to work part time than their male counterparts.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting part-time work |

| Indigenous women | 39% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 44% |

| Indigenous men | 10% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 12% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

It is not known whether the lower rates of part-time work for both First Nations women and men compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts is related to lower access to part-time work. However, the larger rates of part-time work for both groups of women, and the smaller rates for both groups of men, suggest that part-time work continues to be closely associated with gendered norms related to both paid and unpaid labour.

Gender pay equity

First Nations women were overrepresented in lower income brackets and underrepresented in higher income brackets.

Almost 60% of First Nations women reported earning under $95,000 as their full-time base salary, compared to only 38% of non-Indigenous men. Respondents to the People matter survey 2021, from which this data is drawn, were able to select their yearly income from salary brackets increasing in $10,000 increments. These ranged from ‘Less than $45,000’, followed by ‘$45,000-$54,999’, through to ‘$175,000-$184,999’ and finally ‘$185,000 or more’. Respondents were also given the option to select ‘Prefer not to say’. Table 1.3 shows these salary options rolled up into $30,000 groupings.

The average annual full-time salary in Australia, based on the ABS full-time weekly earnings in November 2021, was approximately $91,000 (ABS 2022b). While the options provided to respondents in the People matter survey do not allow analysis of salaries above or below $91,000 specifically, Table 1.3 shows that First Nations women were more likely than men (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) and non-Indigenous women to report a full-time equivalent salary of less than $95,000.

Salary Range | Indigenous women | Non-Indigenous women | Indigenous men | Non-Indigenous men |

| Less than $65,000 | 30% | 22% | 18% | 10% |

| $65,00 – 94,999 | 29% | 32% | 35% | 28% |

| $95,000 –$124,000 | 21% | 22% | 23% | 28% |

| $125,000 –$154,999 | 3% | 5% | 7% | 11% |

| $155,000 –$184,999 | 1% | 2% | 1% | 5% |

| Over $185,000 | 1% | 2% | 2% | 5% |

| Prefer not to say | 9% | 10% | 9% | 9% |

| Unanswered | 5% | 5% | 4% | 4% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Income disparity at the upper end of the pay scale shows the compounding impact of inequality on the basis of Indigenous status and gender. Non-Indigenous men were more than 4 times as likely to report higher incomes than First Nations women (over $125,000), with First Nations men and non-Indigenous women approximately twice as likely to report salaries in these brackets.

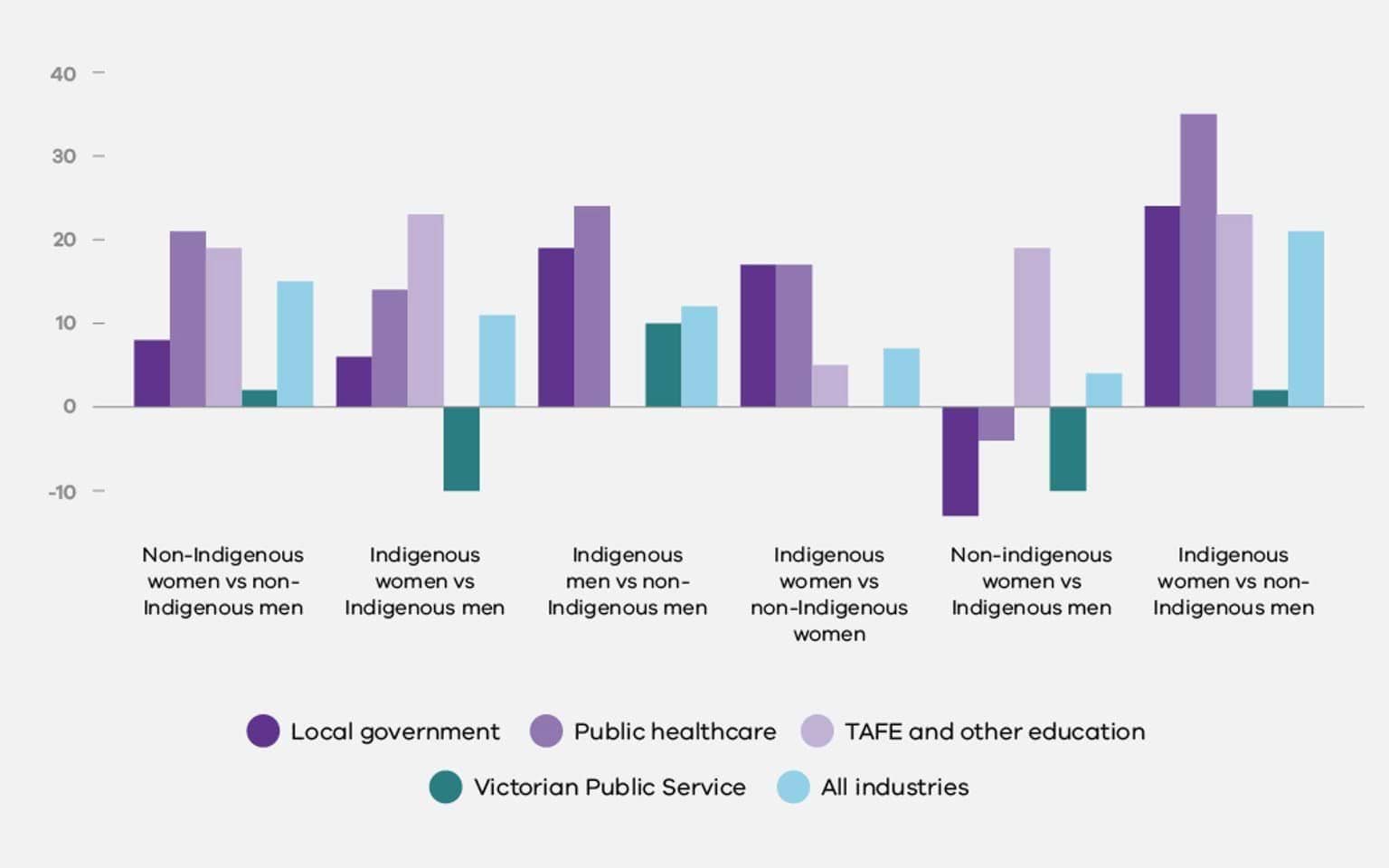

Estimated industry pay gaps were generally largest between First Nations women and non-Indigenous men.

As set out in Table 1.4, across 3 of the 4 industry groups with sufficient data and at the all-industries level, estimated pay gaps were largest between First Nations women and non-Indigenous men. At the all-industries level, the pay gap between these two groups was 21%.

In the Public healthcare industry, the pay gap between First Nations women and non-Indigenous men was the greatest at 35%. The Victorian Public Service industry bucked this trend, with the smallest gap between these groups, at 2%. Notably, First Nations men experienced a significantly larger pay gap than First Nations women when compared to non-Indigenous men in this industry group, and the pay gap between Indigenous women and men was 10% in favour of women.

| Industry | Local government | Public healthcare | TAFE and other education | Victorian Public Service | All industries |

| Non-Indigenous women vs non-Indigenous men | 8% | 21% | 19% | 2% | 15% |

| Indigenous women vs Indigenous men | 6% | 14% | 23% | -10% | 11% |

| Indigenous men vs non-Indigenous men | 19% | 24% | 0% | 10% | 12% |

| Indigenous women vs non-Indigenous women | 17% | 17% | 5% | 0% | 7% |

| Non-indigenous women vs Indigenous men | -13% | -4% | 19% | -10% | 4% |

| Indigenous women vs non-Indigenous men | 24% | 35% | 23% | 2% | 21% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The pay gaps presented here are estimates, produced using a combination of salary bracket data from the People matter survey, outlined above, and the Commission’s workforce remuneration data. This is because the workforce data is not comprehensive enough to produce reliable pay gap calculations based on actual salaries. Please see the Introduction to this report for further detail on the approach taken.

Workplace sexual harassment and discrimination

First Nations women reported experiencing sexual harassment at similar rates to non-Indigenous women.

As Table 1.5 shows, 6.5% of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women reported having experienced sexual harassment at work in the previous 12 months. First Nations men were more likely than their non-Indigenous counterparts to report having experienced sexual harassment.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting sexual harassment |

| Indigenous women | 6.5% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 6.5% |

| Indigenous men | 5.4% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 3.5% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous women were more likely to report experiences of sexual harassment than men, while Indigenous men were more likely than non-Indigenous men to report experiences of sexual harassment.

The two most common types of sexual harassment reported, regardless of gender or Indigenous status, were ‘Intrusive questions about my private life or comments about my physical appearance’ and ‘Sexually suggestive comments or jokes that made me feel offended’.

Please note that the People matter survey 2021 was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was when many people were working from home (except for essential workers, such as healthcare workers). This means that there might have been a potential decrease in certain types of sexual harassment between workers. However, it remains unclear how much the COVID-19 pandemic impacted these numbers.

First Nations people reported experiencing discrimination at higher rates than their non-Indigenous colleagues.

Regardless of gender, First Nations peoples were approximately twice as likely to say they had experienced discrimination in the preceding 12 months as non-Indigenous respondents. Table 1.6 shows these differences in experiences of discrimination.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting discrimination |

| Indigenous women | 10% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 5% |

| Indigenous men | 11% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 5% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The most common type of discrimination reported by First Nations men was being denied opportunities for training and professional development. The most common type of discrimination reported by all three other groups in the table above was being denied opportunities for promotion.

However, First Nations women were more likely than any of the other three groups to select ‘Other’ as the reason for the discrimination, indicating that their experience of discrimination was not listed in the available options. As there was no free text option associated with this question, the type of discrimination the women experienced is unknown. Further research is required to understand First Nations women’s experiences of discrimination in public sector organisations.

Recruitment and promotion practices

First Nations peoples and non-Indigenous women and men were roughly equally likely to agree that recruitment and promotion decisions in their organisations were fair.

As Table 1.7 shows, both First Nations and non-Indigenous people, regardless of gender, were about as likely to agree with the statement ‘My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit’. First Nations women had the highest level of agreement, at 56%.

Indigenous status and gender | My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit | |

Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| Indigenous women | 56% | 19% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 55% | 17% |

| Indigenous men | 53% | 23% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 53% | 22% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

Women and men, regardless of whether they were First Nations Peoples or not, reported feeling they had an equal chance at promotion similar levels.

As Table 1.8 shows, there were only small variations in levels of agreement or disagreement with the statement ‘I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation’ across the four groups. First Nations men had the highest level of agreement, at 49%.

Indigenous status and gender | I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation | |

Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| Indigenous women | 47% | 25% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 46% | 25% |

| Indigenous men | 49% | 26% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 46% | 27% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

Flexible work practices

Women reported higher levels of working flexibly, regardless of whether they were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples or non-Indigenous people.

Both First Nations women and non-Indigenous women were equally likely to report using flexible work arrangements at 31%. Indigenous and non-Indigenous men also reported working flexibly in similar proportions at 22% and 21% respectively. Table 1.9 shows the proportion of respondents in each group who reported using flexible work.

Indigenous status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting flexible work |

| Indigenous women | 31% |

| Non-Indigenous women | 31% |

| Indigenous men | 21% |

| Non-Indigenous men | 22% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Women, regardless of Indigenous status, as well as First Nations men, most often reported using flexible start and finish times. Non-Indigenous men most often reported working part time.

Discussion and conclusions

This chapter aligns with previous research that shows First Nations women face significant barriers to equal participation and outcomes in the workplace. Data from the 2021 workplace gender audit illustrates that First Nations women in Victorian public sector organisations report low rates of occupation of management roles and often much lower salaries than both Indigenous men and non-Indigenous people. In industries with sufficient data, estimated pay gaps showed up to a 35% difference in reported gross salary between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous men.

While reported rates of the experience of sexual harassment and discrimination in the People matter survey 2021 are similar for First Nations women and non-Indigenous women, First Nations men reported experiencing sexual harassment at a higher rate than their non-Indigenous counterparts. As the People matter survey data from 2021 was collected during a period of significant lockdowns in Victoria, it is unclear how working from home conditions may have impacted experiences of sexual harassment.

The Commission’s funded research project found that sexual harassment is a notable concern for First Nations women in the Victorian public sector and indicated that fear of backlash and a lack of faith in systems to address the issue contribute to a lack of formal complaint-making (Bargallie et al. 2023). Fear of lateral violence and abuse, as well as not wanting to detract attention away from other pressing issues for First Nations peoples, provide additional explanations for why Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women might self-censor when reporting their gendered workplace experiences (see Davis 2009).

Crucially, there is a need for identification of the First Nations status of employees in public sector workplaces in Victoria. This data is required to better understand how disadvantage and discrimination on the basis of First Nations status and gender compound to exacerbate experiences of inequality for First Nations women. Better workforce data will help us to calculate pay gaps more accurately, more reliably track harassment and discrimination, explore access to training and other professional development and promotional opportunities, investigate occupational and industrial segregation, as well as to understand the nuances of survey responses. Improved quantitative data, supported by qualitative data from people with lived experience, can help us better address these experiences of inequality.

Despite the data limitations, this chapter reinforces the value of identifying and naming forms of inequality. For First Nations women in the Victorian public sector, Bargallie and colleagues’ research (2023) demonstrates the importance of naming and acknowledging challenges such as the unpaid labour they are expected to do to support reconciliation and education about First Nations peoples in the workplace. The research also points to the need to prioritise the recruitment and retention of First Nations women in the Victorian public sector, including through creating better access to employment outside of metropolitan centres (Bargallie et al. 2023). Access to stable employment is key to ensure First Nations women can grow their careers within the public sector, while effective responses to discrimination and complaints processes are vital to ensure they can safely remain within organisations (Bargallie et al. 2023).

This chapter has focussed on the intersection of discrimination against First Nations peoples and women in the workplace. There is a notable lack of data and information in relation to First Nations peoples of self-described gender. Bargallie and her colleagues’ research emphasised the challenges experienced by LGBTIQ+ Indigenous peoples (2023). These findings demonstrate the urgent need for further research and data collection about this group.

Updated