Reflecting the Commission’s commitment to using the preferred terminology of groups who experience discrimination, this chapter uses the term ‘culturally and racially marginalised’ (CARM) to refer to people who are not white or who are outside the dominant Australian culture. The term CARM encompasses ‘Black, Brown, Asian, or any other non-white group’ (DCA, 2023:5), and it directly acknowledges that people may experience marginalisation because of their culture, race, or religion1. Previous terms such as CALD (culturally and linguistically diverse) and NESB (non-English speaking background) often mask the structures of race and racism that shape the experiences of CARM people (DCA 2023), including in the workplace. In choosing to adopt the term CARM in this report, the Commission acknowledges that language and terminology are evolving in this area, and these conversations remain ongoing. Although the lives of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples are also shaped by structures of race and racism, the Commission does not directly discuss their unique experiences here. Instead, Chapter 1 specifically reports on the workplace experiences of First Nations Australians.

Australia is a culturally diverse nation, built on the contributions of established migrant communities who have built their lives in Australia over many generations, as well as more recent, first-generation migrants. In 2021, 1 in 2 Australians were either born overseas or had parents who were born overseas (FECCA 2022a:17)2. In addition to our cultural diversity, Australia is also increasingly religiously diverse. Over the last 50 years, the number of Australians who describe themselves as Christian has declined. On the other hand, those reporting no religious affiliation, or an affiliation with ‘Other religions’ (an ABS category which includes Hinduism, Islam, Judaism and more) has risen consistently over the last 20 years to 10% of the population (ABS 2022d).

Diversity alone, however, does not translate to equality. Racial inequality in Australia is shaped by the legacy of colonialism (discussed in more detail in Chapter 1, as well as the relationship between the Australian state and non-white immigrants (Elias et al. 2021). The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 (also known as a the ‘White Australia policy’) was one of the first Commonwealth laws passed after Federation. It sought to limit non-white (particularly Asian and Pacific) immigration to Australia (NAA n.d.). Two other key parts of the White Australia policy were pieces of legislation designed to ensure that non-white immigrants could not access work – namely the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 which restricted the entry of Pacific Islanders into Australia, and the Post and Telegraph Act 1901, which required that ships carrying Australian mail employ only white-skinned people (NAA n.d.). The Immigration Restriction Act ended in 1958. Other parts of the White Australia policy, such as the registration of non-British migrants as ‘aliens’, continued into the early 1970s (NAA n.d.).

In the post-war context, international pressure, as well as the need for an increased labour force, saw Australian governments move away from assimilationist policies that required migrant groups to conform to the dominant Australian culture (Elias et al. 2021). However, the legacy of these exclusionary policies continues to impact the experiences of CARM people across multiple facets of their lives, including in the workplace. From 1973, a policy of multiculturalism formally promoted acceptance of diverse cultural communities and a more inclusive migration program (Elias et al. 2021) and the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 made it illegal to discriminate against people based on their race.

Despite the rhetoric of multiculturalism in Australia, CARM groups continue to have unequal access to institutional power and leadership positions as discrimination based on race, cultural background, language or religion persists (Mansouri 29 March 2022; Armillei and Mascitelli 2017). The Scanlon Foundation’s 2021 Mapping Social Cohesion research found that 16% of Australians experienced discrimination because of their skin colour, ethnicity, or religion in the previous 12 months (Scanlon Foundation 2021:30). This figure rose to 34% for people born in a non-English speaking country (Scanlon Foundation 2021:13). CARM people face unique and persistent barriers to health (AIHW 2022b), housing (Blackford et al. 2023), education (Lenette et al. 2019) and personal and communal safety (Afrouz and Robinson 2023; Segrave et al. 2021). CARM people also experience various forms of workplace disadvantage and discrimination, from highly skilled CARM people who are denied appropriate career opportunities, to refugees and asylum seeker populations who experience barriers to accessing entry-level or low-skilled positions (Carangio et al. 2021; Oppare-Addo and Bertone 2020).3

There is very little workforce data and research in relation to gender-diverse Australians who are culturally and racially marginalised. The Commission expects that the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) will drive improved data collection and quality in Victoria to reflect the gender diversity that exists in our society and make gender-diverse cohorts visible. In this chapter, the Commission acknowledges this lack of data on trans and gender-diverse people has meant that issues are generally only able to be analysed and discussed for women and men.

Key workplace issues for CARM people

CARM people face intersecting and systemic barriers to employment, which limit their economic participation, career development, pay and overall job security. According to the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia (FECCA) (2022b:15) some of the systemic workplace inequalities faced by some CARM migrants, depending on their country of origin, may include:

- Lack of recognition of overseas qualifications, skills, and work experience

- Lack of knowledge about Australian workplaces, industries, job application processes and culture

- Pre-migration life experiences, particularly trauma and torture

- Lack of access to upskilling opportunities

- Cost barriers to accessing qualifications and job requirements, such as driving licences

- Caring responsibilities and unaffordable paid care.

These challenges often result in CARM migrants having to take low-paid and low-skilled positions that do not reflect their previous experience and qualifications.

This inequality is not limited to migrant groups, however. Second or third generation CARM people who have grown up in Australia, have Australian qualifications and work experience, and a knowledge of Australian workplace norms, still experience racism across hiring, promotion and career development systems and processes (Leigh 2023). Second and third generation CARM people also still experience interpersonal racism within the workplace, due to racist attitudes and behaviours (Mansouri 2022). Research points to how the limited avenues for reporting racism and racist behaviour in the workplace continue to negatively impact upon CARM people’s inclusion and safety (Annese 2022).

According to the Australian Human Rights Commission (2022b) systemic racism results ‘when cultural norms, laws, ideologies, policies and practices result in the unfair treatment of some groups compared to others’. Interpersonal racism, on the other hand, is racism that occurs between people, at the individual level (DCA 2023). Between 2020 and 2021, almost 40% of all race discrimination complaints received by the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC) were work-related (VEOHRC n.d.). Common examples included racial discrimination in hiring or promotion practices, as well as racist abuse.

Key workplace issues for CARM women

Discrimination is a barrier to participation and progression

CARM women have a lower rate of workforce participation than CARM men (47.3% compared to 69.5%) (WGEA 2023).

CARM women face a range of barriers to employment and career progression based on racist attitudes and assumptions. These include:

- Being denied training and other career advancement opportunities such as guidance and mentoring (DCA 2023; Gyimah et. al. 2022)

- Being overlooked for promotion, despite receiving good feedback (Gyimah et al. 2022)

- Being subjected to a higher bar, underestimated, and negatively singled out compared to non-CARM women colleagues (Diversity Council of Australia 2023)

- Working in culturally unsafe workplaces where practices of racism, sexism, tokensim, and implicit and explicit bias are unaddressed (Pillay 2021)

- Limited recognition of overseas education, work experience, and qualifications (Carangio et al. 2021) and a higher likelihood of working in unstable and casual roles within lower paid industries and sectors as a result (for example, in 2019, 90% of employed male recent migrants were employed full-time compared with 63% of females, (ABS 2020).

Experiences of sexual harassment and gendered violence

International research highlights how gender-based violence is shaped by systemic racism in ways which can increase the risk of violence for CARM women, make them more likely to experience victim-blaming, and limit their access to formal justice (Montoya 2019).

Recent Australian studies reveal inconsistencies in reported rates of sexual harassment and gendered violence towards CARM women. While some studies suggest that CARM and non-CARM women experience sexual harassment at similar rates (AHRC 2018), others suggest that CARM women are twice as likely as to experience sexual harassment as non-CARM women (Baird et al. 2018:92). For migrant CARM women, this disparity may be due to the increased barriers faced in relation to reporting sexual harassment and assault. Navigating difficult visa systems and high rates of insecure employment can make migrant women more vulnerable to exploitation, and less likely to want to challenge and report negative behaviours for fear of legal and economic repercussions (Respect@Work n.d.).

CARM women may also bring a different lens to understanding and identifying instances of sexual harassment. This means that the type of questions asked in surveys, such as whether, for example, a legal or more behavioural definition of sexual harassment is used, can greatly impact upon the types of responses given by CARM women (Respect@Work n.d.). Cultural norms such as gender roles and attitudes to authorities also impact upon CARM women’s recognition and reporting of sexual harassment in the workplace (Welsh et al. 2006; Villegas 2019). Further research is needed to better understand how CARM women experience gendered violence in Australian workplaces.

Workplace and community cultures disadvantage CARM women

CARM women are often required to do additional mental and behavioural work to try to fit into the dominant Australian culture. At the same time, they face workplace discrimination because they do not fit the ideal worker and leadership prototype, which is more masculine and Western (DCA 2023). As a result, CARM women often ‘code-switch’ or enact practices of ‘white-adjusting’ to fit in and try to get ahead by reflecting white workplace cultures (Khadem 2023). This is particularly challenging for women from minority religious backgrounds, who report being unable to freely express and practice their cultural and religious beliefs, such as not shaking hands with men or avoiding situations where alcohol is served (Murray and Ali 2017).

Community cultures can also create challenges to employment for some CARM women. For example:

- Some CARM women face higher cultural expectations relating to domestic and caring work, including cultural expectations that CARM women prioritise immediate and extended family caring needs over paid work responsibilities (FECCA 2022b);

- Some CARM women are pressured by families and communities to work in feminised sectors that are perceived as culturally acceptable. However, these often have higher rates of precarious work and lower salaries (Harmony Alliance 2019); and

- CARM women entering the workforce can threaten traditional male ‘breadwinner’ models of the family in some communities, increasing their vulnerability to domestic and sexual violence (Harmony Alliance 2019).

It should be noted that these assumptions about gender roles cross many cultures and are not confined to CARM populations.

These barriers from the dominant Australian culture, workplace cultures, as well as family and community expectations, present compounding challenges to CARM women’s equal workplace participation.

Commissioned research

In 2022-23, the Commission engaged Dr Ellen Cho and Professor Marie Segrave to undertake research into the experiences of migrant and refugee women employees in 6 Victorian local councils. The focus on migrant and refugee women was designed to complement a broader study funded under the Commission’s 2021 Research Grants Round, which looked at how to achieve workplace equality for culturally diverse women in the Victorian public sector (Pillay et al. 2022). Cho and Segrave undertook 25 online, semi-structured focus group discussions and 4 interviews (by request) with a total of 81 participants. The participants included migrant and refugee women working in the 6 councils, as well as members of each organisation’s executive management teams. The research team investigated how the women experienced gender equality initiatives within their workplaces. They also asked the executive management teams what they thought was needed to support migrant and refugee women to thrive in the workplace. Further details of the research methodology can be found at Victorian local councils and gender equality: Examining commitments to diversity and the experiences of women from migrant and refugee backgrounds.

Key findings

Recruitment

Participants identified discrimination and barriers to participation in the recruitment processes of the councils where they worked. They reported experiences such as having their English proficiency misjudged or having to adopt an English-sounding name to be noticed.

Retention

Retention of migrant and refugee women, and other diverse cohorts, in the local government sector was seen as lacking. Participants reported that their organisations failed to work to retain women from diverse cultural backgrounds. Participants often felt that their employers did not trust their abilities, observed that men were promoted faster than women and believed their access to flexible work options was restricted.

Promotion

Participants identified barriers to promotion. These included assumptions based on traditional gender roles and expectations, such as the false belief that women cannot balance work and childcare. While many people were seen to rely on personal connections to advance their careers, migrant and refugee women were not able to draw on these. Inflexible work arrangements in leadership roles and a lack of migrant or refugee role models in leadership positions were also seen as barriers.

Cultural and language barriers, and a lack of representation in decision-making bodies, were seen as further barriers to career progression. Examples raised by participants included superficial diversity and inclusion policies and practices, as well as poor representation of migrant and refugee women in diversity working groups and in decision-making groups.

Leadership

The leadership styles of women from migrant and refugee backgrounds are often undervalued in local councils. Women participants challenged the narrow understandings of ‘leadership’ within their organisations and reported that their leadership styles were not valued. Some women also felt that their organisations did not see them as reliable or competent, and as a result, that they were constantly having to prove themselves – regardless of their abilities, training or skills.

Reporting sexual harassment and racism

Executive participants expressed concern about the underreporting of sexual harassment in their workplaces. Feelings of a lack of safety on the part of complainants, a lack of trust in the organisation, and a belief that no positive change would come from reporting sexual harassment or other forms of mistreatment were identified as the drivers of low numbers of formal sexual harassment reports. Some executive participants also suggested that a lack of diversity in leadership was a contributing factor to this lack of trust in reporting processes. However, the researchers noted that direct discussions about power inequalities, racism and the drivers of harassment were lacking in these conversations.

CGEPS audit data: Key insights

This section reports on insights from the Commission’s 2021 workplace gender audit workforce data and the 2021 People matter survey (PMS). Workforce data is data drawn from organisations’ human resources and payroll systems. The People matter survey is an anonymous survey completed by approximately 90% of organisations with reporting obligations under the Act.

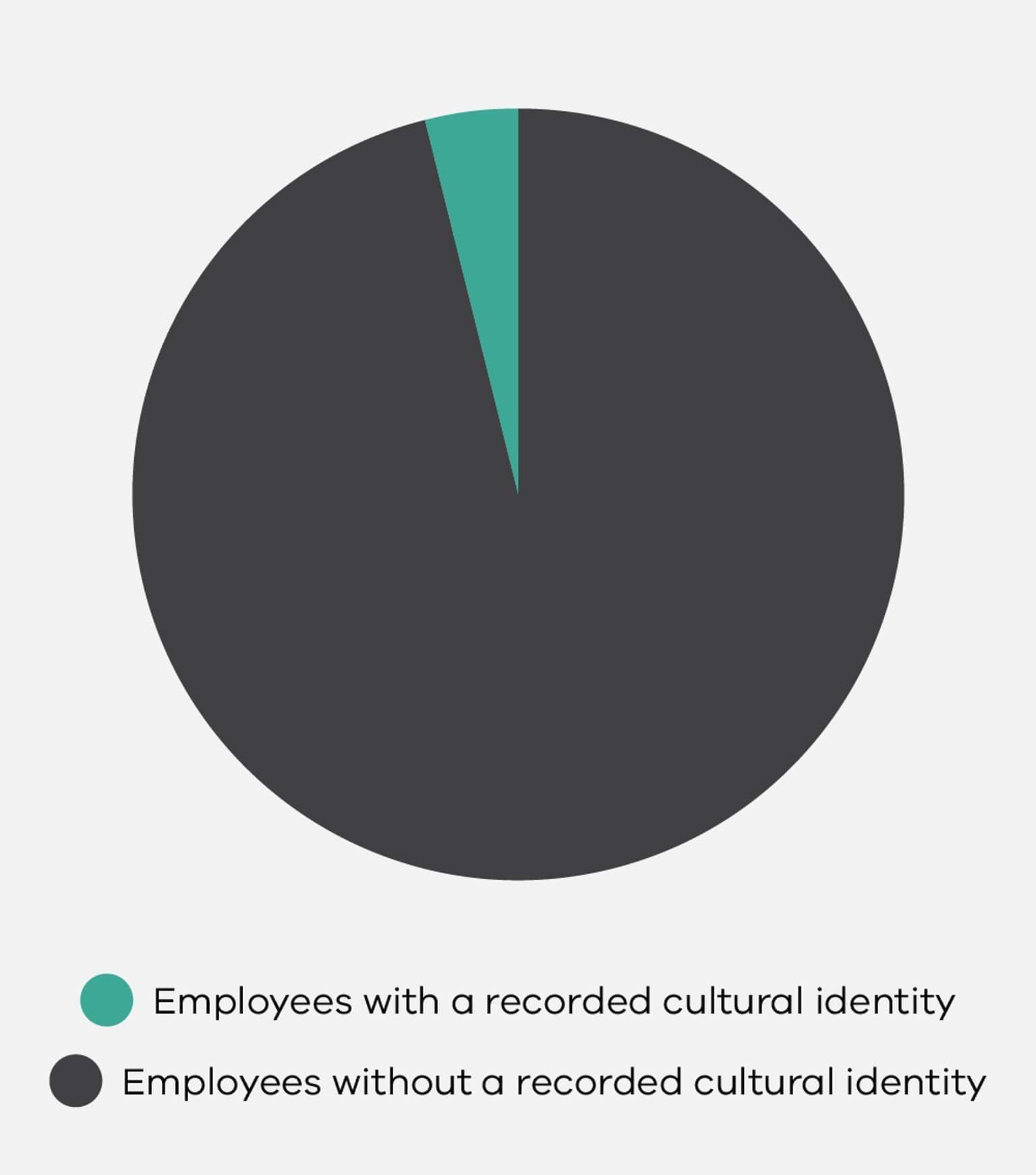

Culturally and racially marginalised employees in the 2021 workplace gender audit

Only 72 organisations (24%) were able to provide any workforce data regarding the cultural identities of their employees, and this data was generally far from comprehensive. Across all organisations with reporting obligations in the 2021 workplace gender audit, only 4% of employees had their cultural identity recorded. The remaining 96% of employees covered by the 2021 workforce data either had no cultural identity recorded or worked for organisations that did not collect and store information about cultural identity through their workforce systems at all.

Having such a small amount of workforce data means it would be impossible to draw any reliable and generalisable conclusions from it. As a result, the data presented in the remainder of this section is derived from the 2021 People matter survey.

Counting CARM women in this report

Considerable challenges exist when organisations and governments attempt to ‘count culture’ in a meaningful way (Allen 2021; DCA 2021). The lack of a standardised approach to measuring cultural diversity and ethnicity in the Australian context means that organisations may rely, for example, only on information from country of birth survey fields, an approach that is likely to exclude some CARM people from the analysis (FECCA 2020). The key tension in data standardisation debates is between approaches that enable simpler conversations around measuring and tracking progress in relation to cultural diversity, versus a more detailed and nuanced approach which better accounts for differences between specific subsets of the CARM population (DCA 2021).

As defined above, this report uses the acronym CARM as a catch-all term for culturally and racially marginalised populations. Ideally, the Commission would be able to usefully tease out some of the distinctions between diverse experiences of discrimination and disadvantage in the workplace on the basis of culture or ethnicity, also taking into account diversities in religious identification and languages spoken. However, given that the available data does not allow for this level of disaggregation the Commission is unable to do so here.

To identify people who should be included in an analysis of the experiences of CARM people in the workplace, it was necessary to construct a proxy measure of this group. This was developed by drawing on responses to the following fields from the People matter survey 2021:

- How would you describe your cultural identity?

- Do you speak a language other than English with your family or community?

- In which country were you born?

In the People matter survey, respondents are asked to select from cultural identity fields. They may select more than one, and some employees elect to use the ‘other’ field and enter free text.

In the analysis of CARM people within this dataset, the Commission included those who selected at least one of the following identities:

- African (including Central, West, Southern and East African);

- Central Asian;

- Central and/or South American;

- East and/or South-East Asian;

- Maori;

- Middle Eastern and/or North African;

- Pacific Islander; or

- South Asian.

The Commission’s decision not to include the categories of North American, New Zealander, and English, Irish, Scottish and/or Welsh poses limitations. For example, this approach does not include people who are both African and North American, but only selected the latter category. In these cases, the Commission cross-checked with the ‘Country of Birth’ field and the ‘Language’ field. When a respondent indicated a country of birth falling within the selections highlighted in the paragraph above, or that they spoke a language other than English with their family or community, the Commission also analysed them as part of the CARM group.

Although the lives of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples are also shaped by structures of race and racism, this chapter does not directly discuss their experiences. Instead, Chapter 1 specifically reports on and analyses the workplace experiences of First Nations Australians.

Taken alone, any of these measures are imperfect for capturing cultural diversity status. The Commission’s approach here, which considers an employee’s identification with a cultural background, language, and country of birth, enables us to build a more complete picture of the cultural diversity that exists within the Commission’s dataset. This approach also reflects the Diversity Council of Australia’s recommended core measures for counting cultural diversity (DCA 2021).

CARM respondents to the People matter survey

Respondents to the People matter survey who identified as coming from backgrounds the Commission categorised as CARM made up 7% of respondents. In terms of gender, 9% of men and 7% of women identified as belonging to these groups. The majority of survey respondents identified as Australian (72%), with a large proportion also identifying as British, Irish or European. A further 11% preferred not to share their cultural identity.

| Cultural Identities | PMS Respondents | Percentage |

| Australian | 75,956 | 71.6% |

| Prefer not to say | 11,223 | 10.6% |

| English, Irish, Scottish and/or Welsh | 8,961 | 8.4% |

| European (including Western, Eastern and South-Eastern European, and Scandinavian) | 7,792 | 7.3% |

| East and/or South-East Asian | 4,732 | 4.5% |

| South Asian | 2,239 | 2.1% |

| Other (please specify) | 2,222 | 2.1% |

| New Zealander | 1,694 | 1.6% |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 1,004 | 0.9% |

| Central Asian | 833 | 0.8% |

| Middle Eastern and/or North African | 734 | 0.7% |

| African (including Central, West, Southern and East African) | 695 | 0.7% |

| North American | 468 | 0.4% |

| Central and/or South American | 372 | 0.4% |

| Maori | 243 | 0.3% |

| Pacific Islander | 291 | 0.2% |

| Total respondents | 106,069 |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. Respondents to the people matter survey are able to select more than one cultural identity. As such, percentages do not add to 100%.

Although data yielded from the People matter survey was greater than the amount received from workforce systems, the relatively small number of respondents identifying as belonging to culturally and racially marginalised groups meant that there was not enough data to generate reliable results in some analyses, such as at the industry level.

Gender composition at all levels of the workforce

Both CARM women and men were underrepresented in managerial roles, but the underrepresentation was greater for CARM women.

As Table 4.2 demonstrates, non-CARM men were far more likely to hold positions as senior managers (overseeing lower-level managers) and supervisors (managing employees who are not managers themselves) than CARM men, and women regardless of CARM status.

| CARM status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting senior manager roles | PMS Respondents reporting supervisor roles |

| CARM women | 3% | 9% |

| Non-CARM women | 7% | 15% |

| CARM Men | 6% | 13% |

| Non-CARM Men | 14% | 21% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Non-CARM men reported holding senior manager roles at almost five times the rate of CARM women, more than two times the rate of CARM men, and exactly twice the rate of non-CARM women. While the disparity in supervisor roles was less stark, non-CARM men were still disproportionately likely to hold supervisor roles.

CARM women were slightly less likely to work part time than non-CARM women.

As seen in Table 4.3 below, 36% of CARM women reported working part time, compared to non-CARM women at 45%. 14% of CARM men reported working part time, whereas the percentage was lower, at 12%, for non-CARM men.

| CARM status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting part-time work |

| CARM women | 36% |

| Non-CARM women | 45% |

| CARM Men | 14% |

| Non-CARM Men | 12% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Gender pay equity

CARM women were overrepresented in lower income brackets and underrepresented in higher income brackets.

60% of CARM women reported earning under $95,000 as their full-time base salary, compared to only 37% of non-CARM men. Respondents to the People matter survey 2021, from which this data is drawn, were able to select their yearly income from salary brackets increasing in $10,000 increments. These ranged from ‘Less than $45,000’, followed by ‘$45,000-$54,999’, through to ‘$175,000-$184,999’ and finally ‘$185,000 or more’. Respondents were also given the option to select ‘Prefer not to say’. Table 4.4 shows these salary options rolled up into $30,000 groupings.

The average annual full-time salary in Australia, based on the ABS full-time weekly earnings in November 2021, was approximately $91,000 (ABS 2022b). While the options provided to respondents in the People matter survey do not allow analysis of salaries above or below $91,000 specifically, Table 4.4 demonstrates that CARM women were more likely than men (CARM and non-CARM) and non-CARM women to report a full-time equivalent salary of less than $95,000.

| Salary Range | CARM women | Non-CARM women | CARM men | Non-CARM men |

| Less than $65,000 | 23% | 23% | 13% | 10% |

| $65,00 – 94,999 | 37% | 32% | 35% | 27% |

| $95,000 –$124,000 | 21% | 23% | 26% | 29% |

| $125,000 –$154,999 | 4% | 5% | 8% | 12% |

| $155,000 –$184,999 | 1% | 2% | 4% | 5% |

| Over $185,000 | 1% | 2% | 4% | 6% |

| Prefer not to say | 6% | 10% | 5% | 9% |

| Unanswered | 7% | 4% | 5% | 3% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Income disparity at the upper end of the pay scale shows the compounding impact of inequality on the basis of race and gender. CARM men reported lower incomes than non-CARM men, but still earnt more than women of all cultural backgrounds. Non-CARM men were almost 4 times as likely to report incomes over $125,000 when compared to CARM women.

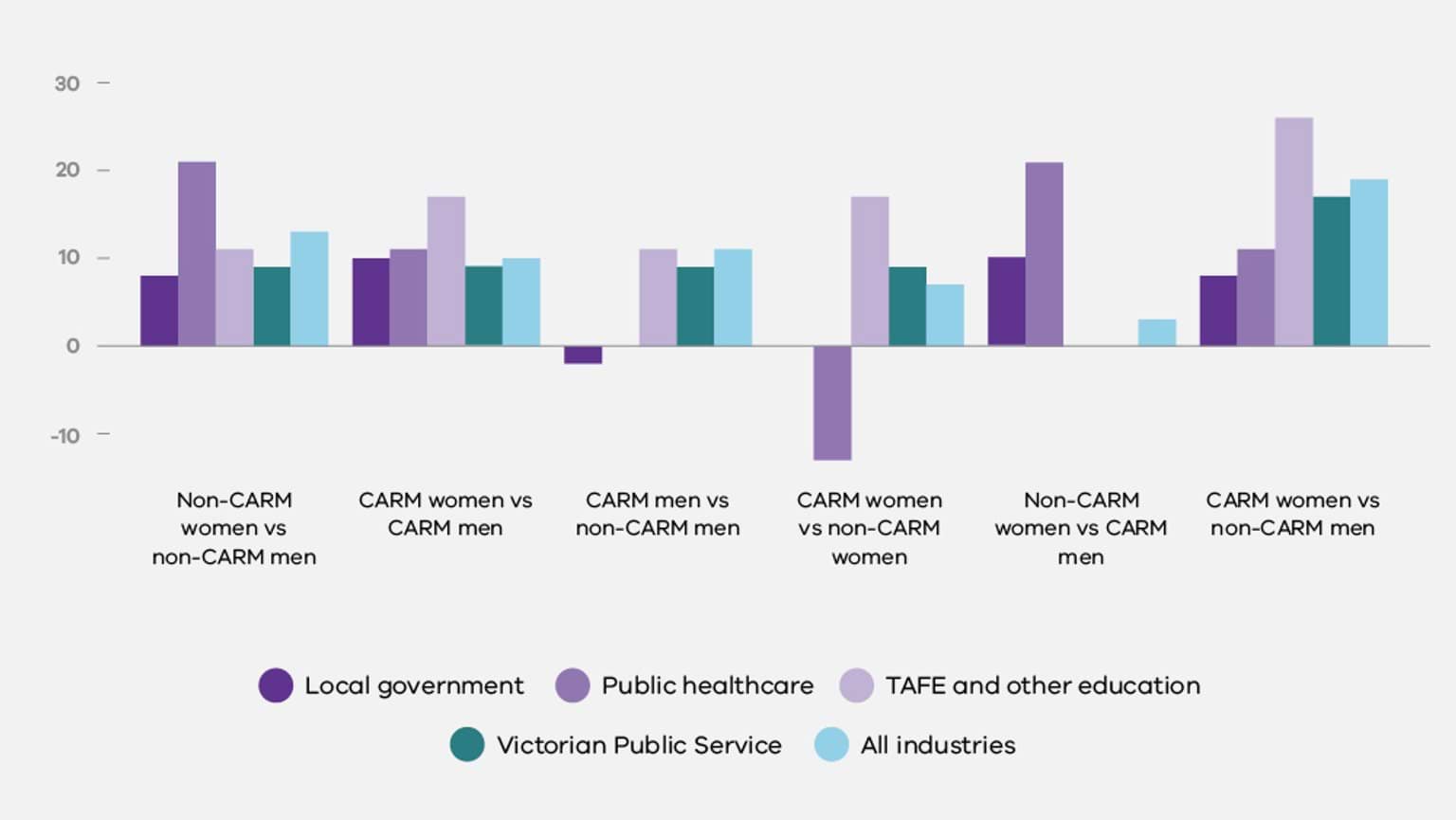

Estimated pay gaps were generally largest between CARM women and non-CARM men.

As set out in Table 4.5, across 3 of the 4 industry groups with sufficient data and at the all-industries level, estimated pay gaps were largest between CARM women and non-CARM men. At the all-industry level, the pay gap between these two groups was 19%.

In the TAFE and other education sector, the gap between CARM women and non-CARM men was largest at 26%. The Local government industry had the smallest gap between these groups, at 8%. Notably, CARM women had a pay gap in their favour in the public healthcare industry, when compared to non-CARM women.

The pay gaps presented here are estimates. They were produced using a combination of salary bracket data from the People matter survey, outlined above, and the Commission’s workforce remuneration data. This is because the workforce data is not comprehensive enough to produce reliable pay gap calculations based on actual salaries. Please see the Introduction to this report for further detail on the approach taken.

| Industry | Local government | Public healthcare | TAFE and other education | Victorian Public Service | All industries |

| Non-CARM women vs non-CARM men | 8% | 21% | 11% | 9% | 13% |

| CARM women vs CARM men | 10% | 11% | 17% | 9% | 10% |

| CARM men vs non-CARM men | -2% | 0% | 11% | 9% | 11% |

| CARM women vs non-CARM women | 0% | -13% | 17% | 9% | 7% |

| Non-CARM women vs CARM men | 10% | 21% | 0% | 0% | 3% |

| CARM women vs non-CARM men | 8% | 11% | 26% | 17% | 19% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Workplace sexual harassment and discrimination

Both CARM women and men reported experiencing lower rates of sexual harassment compared to their non-CARM colleagues of the same gender.

As set out in Table 4.6 below, 7% of non-CARM women reported experiencing sexual harassment in the last 12 months, compared to 4% of CARM women and 4% of non-CARM men. CARM men were least likely to report the experience of sexual harassment (2%).

The People matter survey 2021 was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was when many people were working from home (except for essential workers, such as healthcare workers). This means that there might have been a potential decrease in certain types of sexual harassment between workers. However, it remains unclear how much the COVID-19 pandemic impacted these numbers.

| CARM status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting sexual harassment |

| CARM women | 4% |

| Non-CARM women | 7% |

| CARM Men | 2% |

| Non-CARM Men | 4% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Regardless of gender and CARM status, the two most common types of sexual harassment reported were ‘Intrusive questions about my private life or comments about my physical appearance’ and ‘Sexually suggestive comments or jokes that made me feel offended’.

Reported rates of the experience of workplace discrimination were similar across CARM and non-CARM groups and genders.

CARM women were most likely to report experiencing discrimination in the last 12 months and non-CARM men were least likely to report experiencing discrimination. However, these differences were small. Table 4.7 shows these marginally different rates across the four groups.

| CARM status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting discrimination |

| CARM women | 6% |

| Non-CARM women | 5% |

| CARM Men | 5% |

| Non-CARM Men | 4% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The most common type of discrimination reported by all four groups was being denied opportunities for promotion.

Recruitment and promotion practices

CARM people, regardless of gender, were more likely to agree that recruitment and promotion decisions in their organisations were fair.

As Table 4.8 shows, CARM men and women were more likely than non-CARM people to agree with the statement ‘My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit’. CARM men had the highest level of agreement, at 68%.

| CARM status and gender | My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit | |

| Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| CARM women | 67% | 10% |

| Non-CARM women | 54% | 17% |

| CARM Men | 68% | 10% |

| Non-CARM Men | 51% | 23% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

CARM people reported feeling they had an equal chance at promotion at higher rates than their non-CARM colleagues.

As Table 4.9 shows, CARM women and men were more likely than their non-CARM peers to agree with the statement ‘I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation’. CARM men had the highest level of agreement, at 54%.

| CARM status and gender | I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation | |

| Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | |

| CARM women | 51% | 18% |

| Non-CARM women | 46% | 25% |

| CARM Men | 54% | 18% |

| Non-CARM Men | 46% | 27% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

Flexible work practices

Women were more likely than men to report flexible work, regardless of CARM status.

Both CARM women and non-CARM women reported flexible work arrangements at the same rate, which was higher than that of both CARM men and non-CARM men. Table 4.10 highlights the proportion of respondents in each group who reported accessing flexible work opportunities.

| CARM status and gender | PMS Respondents reporting flexible work |

| CARM women | 31% |

| Non-CARM women | 31% |

| CARM men | 23% |

| Non-CARM men | 23% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Women, regardless of CARM status, most often reported using flexible start and finish times. CARM men also reported using flexible start and finish times most often, while non-CARM men most often reported working part-time.

Discussion and conclusion

This chapter demonstrates how gender and race-based inequalities combine to create systemic challenges for culturally and racially marginalised women in public sector workplaces. Much research has found that CARM women face a range of systemic barriers to career progression. These findings are consistent with the Commission’s data analysis which shows that CARM women are less likely to report holding management roles and are more likely to indicate lower salaries – this is despite the finding that both CARM women and men reported higher agreement compared to their non-CARM colleagues that recruitment and promotion in their organisations is fair and that they have an equal chance at promotion in their organisations.

The Commission’s workplace gender audit data and its funded research project by Cho and Segrave demonstrate the importance of improved data collection about people of different genders from CARM backgrounds. Data is required to better understand how discrimination on the basis of cultural background and gender combine to produce unique barriers to workplace equality for particular groups. The lack of workforce data on cultural identity, and thus the need to rely on survey data that is not linked to employee records, meant that this analysis was unable to explore the access to training and other professional development and promotional opportunities, as well as occupational and industrial segregation of CARM people in Victorian public sector organisations. The Commission also had to estimate pay gaps rather than being able to rely on precise salary data.

Discrimination in recruitment and retention processes is a particular area requiring focussed attention from organisations (Cho and Segrave 2023). Cho and Segrave report that migrant and refugee women found that their proficiency in English was often misjudged, and they were frequently overlooked unless they used an English-sounding name (Cho and Segrave 2023). These findings reflect existing evidence that in order to progress their careers, CARM women feel pressure to assimilate to dominant workplace cultures that reflect a Western ideal, minimising their own experiences and identity (DCA 2023; Khadem 2023). Biases around recruitment can also flow through to retention, with CARM women experiencing a lack of trust in their professional abilities from managers and organisations (Cho and Segrave 2023; Gyimah et al. 2022).

Moving towards more meaningful diversity and inclusion practices that centre the voices of CARM women and address conscious and unconscious cultural and racial biases can support organisations to improve equality for CARM women. These goals can begin to be achieved through focussing on redressing inequalities in access to training and development opportunities, and paying attention to the role of managers in supporting career progression and ensuring promotion pathways are transparent (Cho and Segrave 2023; Gyimah et al. 2022. Ensuring that CARM women are able to meaningfully participate in diversity and inclusion initiatives, for example as members of relevant committees, can help tackle the root causes that hinder CARM women’s equal participation in the workplace (Cho and Segrave 2023). Involving CARM women, and other diverse people, in these processes can also help ensure that impacted groups have faith in equality programs and do not see them as a tick-box exercise (Cho and Segrave 2023).

Ensuring increased representation of CARM women in leadership will also foster a more inclusive environment – one where CARM women feel more comfortable voicing their concerns. Research has found that reduced feelings of trust and safety in their organisations, particularly where this representation was absent, contributed to CARM women feeling too uncomfortable to report experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace (Cho and Segrave 2023; Respect@Work n.d.).

Research funded by the Commission in its Inaugural Research Grants Round in 2021 identified key whole-of-organisation approaches to achieving gender equality for culturally diverse women. Importantly, the researchers found that organisations must take a holistic approach to change across multiple scales, including systemic, organisational and individual change (Pillay et al. 2022). To ensure accountability for progress, organisations should set metrics and targets, ensuring leaders are responsible for achieving these goals (Pillay et al. 2022). Reviewing policies to ensure they are free from discrimination is vital to remove systemic forms of discrimination embedded in processes and established ways of doing things (Pillay et al. 2022). Lastly, visible leaders who lead change through active advocacy and sponsorship for CARM women are central to ensuring an inclusive workplace is established from the top (Pillay et al. 2022).

Further research is needed to continue to unpack the ways in which specific aspects of disadvantage and discrimination against CARM people intersect with gender-based discrimination to produce unique experiences of inequality. Importantly, there is also more data and research needed to better understand how people of self-described gender from CARM backgrounds experience public sector workplaces.

- The background material in this chapter addresses race, culture, and religion together. This is because racist attitudes and structures use characteristics such as culture, religion, language, and nationality to perpetuate discrimination against CARM people (Ben et. al. 2022, p. 2). The Commission acknowledges the huge amount of diversity both between and within these categories which cannot be covered appropriately here. The Commission is unable to report on religion in this chapter due to challenges related to analysing the small amount of data available.

- It is important to note that this figure includes white, Western and privileged migrants, such as many of those coming from the United Kingdom (Carangio et al. 2021), and does not account for the huge wealth of cultural diversity within Australia in established families and communities who may have been here for more than two generations.

- Research and data about workplace discrimination against CARM people, particularly in public sector contexts, has a strong focus on the experiences of migrants and people who speak a language other than English with their family or community (e.g. Oppare-Addo & Bertone 2020; VPSC 2023c). This is partly based on the data available, which often relies on information about country of birth and languages spoken, and partly because migrant people frequently face acute forms of disadvantage and discrimination. This report takes a broader definition of CARM to encompass cultural diversity beyond migrant and refugee people, but the Commission acknowledges that there remains a strong focus on migrant experiences in this chapter, which may not be the dominant experience for CARM people within the Victorian public sector.

Updated