Ageism is a set of beliefs (stereotypes), emotions (prejudice) and actions (discrimination) directed towards people on the basis of age (AHRC 2021b). While it is usually targeted by one age group against another, ageism can also be directed towards people in the same age group (Blackham 2022; AHRC 2021b). Ageism is also sometimes internally focused or self-directed, affecting how we perceive our own abilities in relation to prejudicial attitudes (Hausknecht et al. 2020).

Ageism does not receive as much attention as other forms of discrimination, such as sexism or racism (AHRC 2021). The former Australian Federal Age Discrimination Commissioner Dr Kay Patterson described ageism as “…the least-challenged and understood form of discrimination” (Patterson 28 July 2023) and the World Health Organisation (2021) noted that it is still largely socially accepted. Despite the existence of national and state-based legislation which makes ageism unlawful, it is prevalent across Australian society (O’Loughlin et al. 2017) with negative impacts on inclusion and wellbeing (AHRC 2021b). A recent study into ageist attitudes by the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) found 90% of participants believed ageism exists, and 63% reported they had experienced ageism in the last 5 years (AHRC 2021b).

Ageism affects Australians throughout adult life. The AHRC (2021b) categorises Australians into 3 adult life stages, each with their own commonly applied stereotypes:

- Older adults (62+ age range): Perceived as likeable, warm, more loyal, reliable, and aware, and as mere spectators of life experiencing declining skills and life roles rather than as active participants in the workplace and in wider society.

- Middle aged (40-61 age range): Viewed as being in the prime of their career but stressed due to the competing demands of raising dependents and managing workplace responsibilities.

- Young adults (18-39 age range): Seen as attractive, inexperienced, irresponsible, self-centred, prone to taking risks, and having greater career ambitions and technological and physical capabilities.

Literature on ageism often focusses on understanding impacts on older adults. However, the AHRC also found that ageism can have significant negative impacts on young adults, with further research required to better understand these (AHRC 2021).

Research and evidence suggest that ageism can impact people differently across these broad age categories, and that these experiences are shaped by gender inequality. This chapter highlights the ways that biases and discrimination on the basis of age and gender intersect, creating negative outcomes for women in the workplace across the course of their lives. As research on the ‘double jeopardy’ of ageism and gender highlights, women are never perceived to be the ‘right’ age, and their workplace experiences are always marked by this form of compounded discrimination (Harnois 2015; Blackham 2023).

There is very little data and research in relation to gender-diverse Australians in the workplace across different life stages. The Commission expects that the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act) will drive improved data collection and quality in Victoria to reflect the gender diversity that exists in our society and make gender-diverse cohorts visible. In this chapter, the Commission acknowledges this lack of data on trans and gender-diverse people has meant that issues are generally only able to be analysed and discussed for women and men.

Key workplace issues related to ageism

Although Australians are typically spending a larger portion of their lives in the labour market, age discrimination remains a significant barrier to equal participation. Young adults and older Australians are often considered “too old” or “too young” for relevant positions (O’Loughlin 2017, p. 98). In 2015, the Australian Human Rights Commission conducted a survey that revealed age discrimination was frequently experienced by older individuals seeking paid work. Nearly 58% of job-seekers aged over 50 reported discrimination based on age (AHRC 2015:9), and 27% of those aged over 50 who were currently employed reported experiencing age discrimination in the workplace in the past two years (AHRC 2015:9).

Employers’ perceptions of older workers reinforce these experiences. The same study revealed that negative attitudes toward older workers' ability to learn and upskill were a prevalent form of age-based discrimination, with 44% of managers aged 50 years or older reporting that they factor in a person’s age when making hiring decisions (AHRC 2015:9). A 2023 survey of human resources professionals found that while almost two thirds (65 per cent) of respondents said they were currently finding it difficult to recruit people into roles, only 56 per cent said that they were open to recruiting people aged between 50 and 64, and only 25 per cent were open to hiring those aged 65 and over (Australian HR Institute and AHRC 2023:11). Such ageist attitudes underpin the finding that older unemployed individuals take twice as long as younger unemployed individuals to secure employment, and some may never find work again (Patterson 2021).

Despite the significant impacts ageism has on the experiences of older Australians at work, Australians are remaining in the workforce for longer. This is due to many factors, including increasing life expectancies and costs of living (ABS 2022c; AIHW 2023b). A higher proportion of Australians now report that they expect to retire between 66 and 70 years of age (39.6% in 2021, up from 37.4% in 2018 and 31.9% 2014) (AHRC 2021a:11). Furthermore, the proportion of workers aged 55+ has more than doubled from 9% in 1991 to 19% in 2021. Unfortunately, barriers related to ageism mean many older people may spend decades of their lives without paid employment (AHRC 2015), exacerbating issues related to financial insecurity and social isolation.

Younger workers face different challenges. Labour laws often fail to protect younger workers or can even discriminate against them. This includes through unpaid internships and work placements (Blackham et al. 2022), junior rates based on age rather than skill level or work performed (YWC 2022), and employers only paying superannuation contributions to workers under 18 if they work more than 30 hours per week (YWC 2022).

Younger workers also face high levels of exploitation. Issues such as wage theft and insecure employment are prevalent. These can be exacerbated by the high uptake of casual work among younger workers, which also results in a lack of leave entitlements (YWC 2020). Some managers take advantage of young workers' lack of experience in occupational health and safety, forcing them to work in hazardous conditions to cut costs. In a recent survey, one in four young workers had been asked to perform unsafe tasks, and 55.6% of those complied (YWC 2017:12). Additionally, half of the young workers surveyed reported experiencing bullying or harassment at work. These abuses are compounded for international students, as their visa status and lack of knowledge about workplace rights make them vulnerable to exploitation and coercion (YWC 2020).

Key workplace issues related to ageism and gender

When ageism combines with sexism, it can exacerbate inequalities for women in the workforce. Women are more likely than men to receive negative and unequal treatment based on age (Blackham 2022; Handy and Davy 2007), with research long demonstrating that this can occur at various stages across a woman’s life (Duncan and Loretto 2004).

Sexist attitudes can combine with ageism to produce or increase specific forms of discrimination at different points in women’s lives. This ‘gendered ageism’ works to undermine women's leadership, reinforce rigid gender roles, limit women's personal autonomy, and normalise discrimination against them (Blackham 2022; Handy and Davy 2007).

Younger women

Younger workers – regardless of gender – can face particular forms of exploitation and discrimination, as well as biases and negative attitudes. For young women, these challenges can be compounded by gender-based discrimination. Barriers to workplace equality or forms of negative treatment that young women are more likely to experience include (Duncan and Loretto 2004; YWC 2020):

- Lower access to paid employment

- Larger early career wage gaps

- Discriminatory attitudes and assumptions about capability

- Bias in recruitment

- A lack of access to progression and promotion opportunities

- Appearance-based discrimination or harassment

- Increased risk of sexual harassment by bosses, managers, colleagues, and customers.

Australian and international evidence also shows that, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, young women experienced greater job losses, mental ill-health, and increased care responsibilities that impacted access to paid employment (ILO 2021; Loxton et al. 2021).

Older women

Ageism affects older women differently to older men. According to the Australian Human Rights Commission, older women (51%) are more likely than older men (38%) to be perceived by their peers as having outdated skills, being slow to learn new things, or doing an unsatisfactory job (AHRC 2015). Older women are more likely to be discriminated against based on their appearance as they grow older, which can negatively impact their sense of self-worth (AHRC 2016; Handy and Davy 2007; McGann et al. 2016). Their workforce participation can also be affected by a lack of workforce accommodations related to menopause. Workers’ menopause symptoms can be exacerbated by restricted access to toilets, inability to control ventilation and air conditioning, restrictive workwear, and uncomfortable workstations (Circle In 2021). A 2021 survey found that 83% of women who experienced menopause reported that it negatively affected their work life, with one in two women considering retirement or extended leave as a result (Circle In 2021:4)

Middle-aged women

Women in their middle years can begin to experience the compounding impacts of lifetime gender inequality, and face challenges related to an increased care burden when compared to men. Women tend to have more caring responsibilities across all stages of life, with 72% of primary carers in Australia being women (ABS 2019). Caring responsibilities can impact women’s workforce participation as they may need greater access to leave, part-time employment or flexible working opportunities to be able to provide care (Dangar et al. 2023). In their middle years, this care burden can increase, with young children and older parents often requiring care at the same time (Vlachantoni et al. 2020). Care is more commonly performed by historically marginalised communities, such as First Nations peoples, people of colour, queer-identifying, religious minorities, youth, and those with disabilities (Dangar et al., 2023). This means that mid-life caring challenges may be further compounded for those experiencing intersecting forms of disadvantage.

Ageism related to parenting

Although unlawful, mothers are especially disadvantaged by workplace discrimination. Biases related to motherhood are often extended to people who are perceived as women and of child-bearing age (Peterson Gloor et al. 2021; Thomas 2020). As such, these attitudes often disproportionately affect women, or people perceived as women, in their mid-20s to late-30s. Women without children are more likely to experience expectations about parenthood than those who are already parents (Peterson Gloor et al. 2021). Discrimination against people in this demographic often arises from managers’ uncertainty about future childbearing intentions. Pregnancy and caring are viewed as future organisational risks where leave or other workplace rights may result in productivity losses or increased costs (Peterson Gloor et al. 2021).

The Australian Human Rights Commission asserts that these systemic issues of employers discriminating against women for pregnancy-related reasons are widespread throughout Australia. These biases and prejudice towards potential or actual caring responsibilities create barriers which can prevent women from fully participating in Australian workforces (AHRC n.d.).

Commissioned research

In 2022-23, the Commission engaged Associate Professor Alysia Blackham, Professor Leah Ruppanner, Professor Beth Gaze, Professor Susan Ainsworth, Dr Brendan Churchill, Kate Dangar, Mira Gunawansa, Lía Acosta Rueda, and Cameron Patrick to examine the impact of pregnancy, parenting and caregiving on workplace gender equality in the Victorian public sector. While the research project did not explicitly examine the experience of people of different ages, this chapter highlights the links between age-based gender inequalities and gendered caring expectations. For this reason, the Commission has included a summary of this research project here.

The researchers undertook 74 interviews with Victorian public sector workers in relation to work and care responsibilities. Of the 74 public sector workers interviewed, 86.5% were women, 10.8% were men, 1.4% were non-binary, and 1.4% preferred not to disclose their gender.

They also conducted an online survey, with a total of 349 respondents who worked in VPS departments, agencies and organisations across metro, regional and rural Victoria. Of these, 88.2% of respondents were women, 9.8% were men, 0.8% were non-binary or gender-diverse, and 0.8% preferred not to disclose their gender.

Further details of the research method can be found in the research project Caring and Workplace Gender Equality in the Public Sector in Victoria.

Key findings

Flexible work arrangements

More women and non-binary people reported being caregivers, and invested much more time in caregiving activities, compared to men. Encouragingly, participants identified workplace flexibility as a notable strength of the Victorian public sector. The research also found that how leave entitlements and flexible work arrangements were accessed depended highly on individual managers. Most respondents in the research reported not being informed of their rights as caregivers in the workplace. Additionally, a significant portion of respondents found that the amount of leave entitlements wasn’t enough and challenging to access.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted discussions around allowing caregivers to work flexibly as the norm. Nevertheless, respondents said there was a push to return to pre-pandemic norms in the workplace. This created uncertainty among caregivers, who feared that the level of flexibility they had may not be sustained in the future.

Career progression opportunities

Caregivers participating in the research, particularly working mothers and mature-aged women (50+ years) were notably less likely to report being offered opportunities for career progression. Most respondents believed that having caregiving responsibilities can be a barrier to career success in the Victorian public sector. This contrasted with the results of the People matter survey (PMS), where 59% of women and 62% of men agreed or strongly agreed that caregiving responsibilities did not impede career success. Furthermore, only 40% of non-binary respondents to the People matter survey agreed that caregiving responsibilities were not a barrier to career success. The researchers note that these findings highlight that it is important to consider gender differences beyond the binary in experiences of caregiving.

Discrimination against carers

Respondents described how discrimination against caregivers in the workforce endured without being properly addressed. People of diverse backgrounds experienced additional barriers and discrimination in the workplace due to their caregiver status. However, despite higher levels of caregiving among First Nations peoples, people of colour, queer-identifying, religious minorities, people with disabilities and youth, the research team notes that these groups were underrepresented in the study. Further research is required to better understand how these historically marginalised groups experience care at work. The study found that individuals taking leave for traumatic reasons (such as for miscarriage or domestic violence) were less likely to receive sufficient or well-informed support. Finally, caregivers in the study reported that insecure employment further compounded challenges they faced and deterred some from using their leave and flexible work entitlements.

Recognising diverse types of caring

The research team emphasised the importance of recognising that experiences of caregiving can be extremely varied. This includes differences in who a person cares for, as well as how they practice that care and therefore the types of accommodations they may require from their employer. As such, understanding how different organisational policies related to flexible working arrangements and leave entitlements impact employees with different caregiving responsibilities is key to ensuring that carers, primarily women, can participate equally at work. Additionally, participants with non-normative experiences of caregiving – such as caregiving outside of an immediate heterosexual family, men with caring responsibilities, or practices of community care – reported facing a lack of empathy and support at higher rates than those in heterosexual relationships who were caring for their children.

CGEPS audit data: Key insights

This section reports on insights from the Commission’s 2021 workplace gender audit workforce data and the 2021 People matter survey (PMS). Workforce data is data drawn from organisations’ human resources and payroll systems. The People matter survey is an anonymous survey completed by approximately 90% of organisations with reporting obligations under the Act.

In the People matter survey, respondents were able to select one of the following response options to the question ‘What is your age range?’:

- 15-24 years

- 25-34 years

- 35-44 years

- 45-54 years

- 55-64 years

- 65+ years

- Prefer not to say

The majority of the analysis below uses the People matter survey data, and therefore uses these age brackets (or combinations of them) in reporting.

In the companion to this report, the Baseline report, the Commission reported on pay gaps disaggregated by both age and gender. The Commission has not re-created pay analyses again here, but instead has summarised the findings reported in the Baseline.

It is important to note that while age is the largest and most well-reported demographic variable examined in this report (aside from gender), this means that the age categories discussed below mask significant amounts of diversity in Aboriginality, ability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion and sexual orientation. Given that the average public sector employee is white, straight, cis-gendered, able-bodied and is not a First Nations person (VPSC 2022a), the average experiences across age demographics here are likely to reflect this dominant group most closely. This is one of the limitations of analysing gender plus one other demographic variable, and the Commission acknowledges that there is more to do to understand experiences across the life-course of people facing intersecting inequalities.

Employees of different age groups in the 2021 workplace gender audit

Organisations participating in the 2021 workplace gender audit supplied comprehensive data about the ages of their employees. Age was the most consistently reported attribute aside from gender. Age-range information was provided for 93% of all employees included in the workforce data reporting (data drawn from organisations’ human resource management systems).

The comprehensive age data supplied by organisations participating in the 2021 workplace gender audit means that it is possible to produce meaningful analysis related to age from the workforce data collected under the Act. However, this chapter focusses primarily on the People matter survey data in order to provide comparable data across all of the chapters in this report.

Gender composition at all levels of the workforce

Women were less likely than men to hold managerial positions across all age groups.

As illustrated in Table 2.1 below, men were more likely to report holding senior manager positions (overseeing lower-level managers) and supervisor roles (managing employees who are not managers themselves) in every age bracket. Women’s representation in senior manager (10%) and supervisor (18%) roles peaked in their middle years (45-54 years). Although men’s representation peaked in the same age range, they reported holding senior manager roles at almost twice the rate of women. At ages 55+ men were more than twice as likely to hold senior management positions.

Gender

| Age group | PMS Respondents reporting senior manager roles | PMS Respondents reporting supervisor roles |

| Woman | 15-24 years | 0% | 1% |

| Man | 15-24 years | 0% | 2% |

| Woman | 25-34 years | 3% | 10% |

| Man | 25-34 years | 4% | 12% |

| Woman | 35-44 years | 8% | 18% |

| Man | 35-44 years | 13% | 22% |

| Woman | 45-54 years | 10% | 18% |

| Man | 45-54 years | 19% | 23% |

| Woman | 55-64 years | 7% | 16% |

| Man | 55-64 years | 15% | 21% |

| Woman | 65+ years | 4% | 12% |

| Man | 65+ years | 9% | 16% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

The gaps between the proportion of women and the proportion of men reporting managerial roles grew in each age bracket after 25-34 years.

Gender pay equity

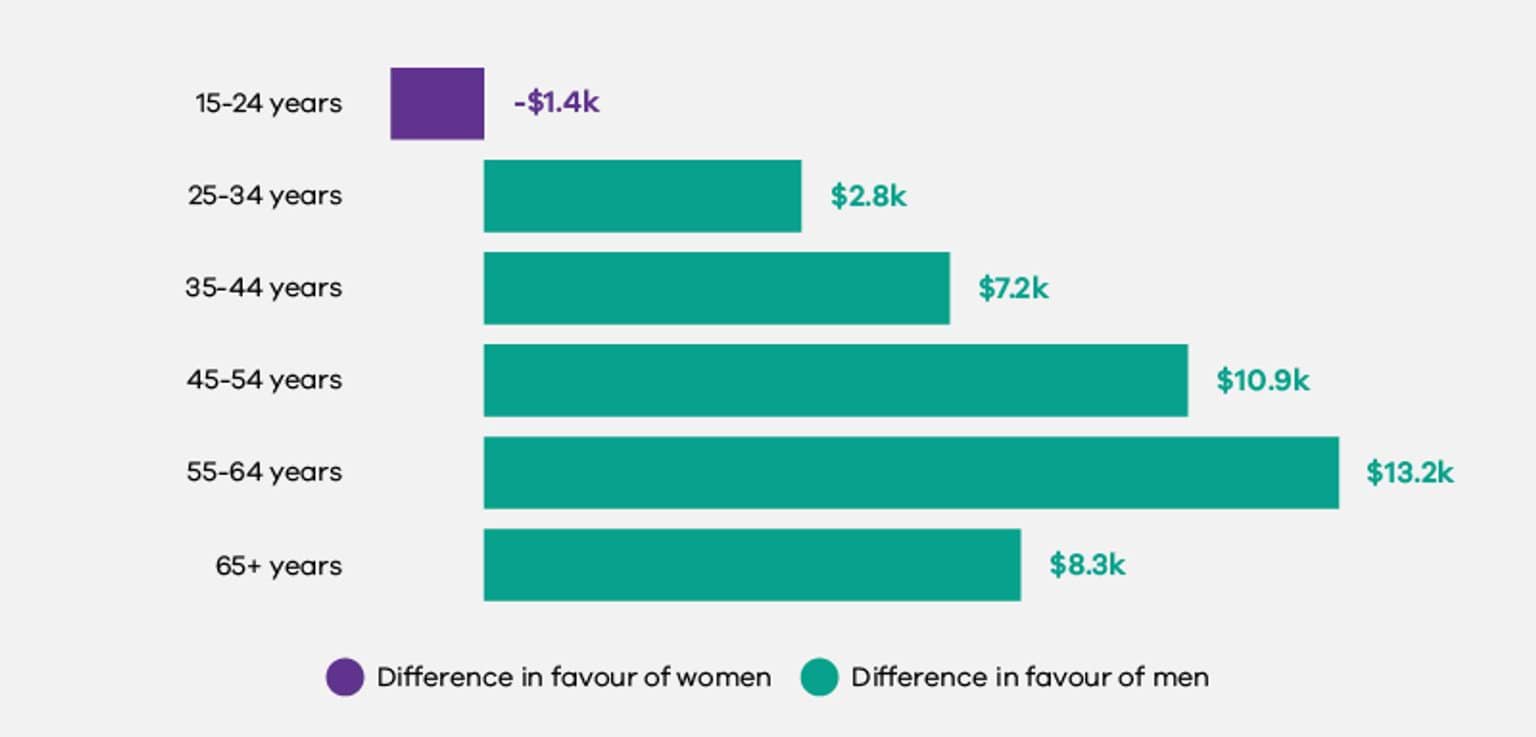

Gender pay gaps in favour of men increased in all age brackets from 25-34 years until 65+.

The companion to this report that was published by the Commission in 2022, the Baseline report, used workforce data from the 2021 workplace gender audit to calculate pay gaps across each age bracket. These pay gaps were calculated using median base salaries – meaning a person’s salary before any bonuses, superannuation, overtime, salary-packaging or other extra payments are included – as reported from organisations’ payroll systems. This approach is more precise than the estimated pay gaps used in other chapters of this report (see the Introduction for more information on this approach).

The pay gap analysis reported in the Baseline report showed that the gender pay gap favouring men is smallest for employees aged between 25 and 34 years, with women in this age bracket earning a median base salary 3.3% lower than men in the same age group. This gap begins to widen significantly for women in the 35 to 44 years age bracket (7.2%) and continues to widen for women in the next age bracket, 45 to 54 years (10.8%). The gender pay gap increases to its highest point (13.7%) for women aged 55 to 64 years. Women in this age bracket have median base salaries $13,200 lower than their male counterparts. Figure 2.2 is replicated from the Baseline report and illustrates the widening pay gaps between women and men until age 65+.

See the Commission’s Baseline report for further information and discussion.

Workplace sexual harassment and discrimination

Younger women reported experiencing sexual harassment at the highest levels compared to any other age group.

Women of all ages reported experiencing sexual harassment at a higher rate than men in the same age bracket, except people aged 55+. Table 2.2 sets out the percentage of respondents to the People matter survey who reported experiencing sexual harassment in the previous 12 months.

| Age | Gender | PMS Respondents reporting sexual harassment |

| 15-24 years | Women | 14% |

| 15-24 years | Men | 4% |

| 25-34 years | Women | 11% |

| 25-34 years | Men | 5% |

| 35-44 years | Women | 6% |

| 35-44 years | Men | 4% |

| 45-54 years | Women | 5% |

| 45-54 years | Men | 3% |

| 55-64 years | Women | 3% |

| 55-64 years | Men | 3% |

| 65+ years | Women | 2% |

| 65+ years | Men | 2% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Younger women, aged 15-24, reported experiencing the highest levels of sexual harassment of any age group at 14%. This is almost four times the 4% rate reported by men in the same age group. The second highest prevalence of the experience of sexual harassment was for women aged 25-34 years at 11%. This was more than double the rate reported by men in the same age category.

The two most common types of sexual harassment reported, regardless of gender or age, were ‘Intrusive questions about my private life or comments about my physical appearance’ and ‘Sexually suggestive comments or jokes that made me feel offended’.

The People matter survey 2021 was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was when many people were working from home (except for essential workers, such as healthcare workers). This means that there might have been a potential decrease in certain types of sexual harassment between workers. However, it remains unclear how much the COVID-19 pandemic impacted these numbers.

Regardless of age or gender, respondents reported experiencing discrimination at similar rates.

As shown in Table 2.3, women at each age bracket were similarly likely to report having experienced discrimination in the previous 12 months compared to men. While women reported experiencing discrimination at marginally higher rates in most age brackets, the exceptions to this include at ages 25-34 and 55-64 where the rate was even across the two genders, and 45-54, where men reported 1% higher rates of discrimination.

| Age | Gender | PMS Respondents reporting discrimination |

| 15-24 years | Woman | 4% |

| 15-24 years | Man | 3% |

| 25-34 years | Woman | 5% |

| 25-34 years | Man | 5% |

| 35-44 years | Woman | 6% |

| 35-44 years | Man | 5% |

| 45-54 years | Woman | 5% |

| 45-54 years | Man | 6% |

| 55-64 years | Woman | 5% |

| 55-64 years | Man | 5% |

| 65+ years | Woman | 5% |

| 65+ years | Man | 4% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Being denied opportunities for promotion was the most common type of discrimination reported among all age groups and genders, aside from 15–24-year-old women. Women in this age group were more likely to report being denied opportunities for training or professional development, while being denied opportunities for promotion was the second most common form of discrimination selected by this cohort.

Recruitment and promotion practices

Younger people were more likely to agree that recruitment and promotion decisions in their organisations were fair.

As Table 2.4 shows, women and men were roughly equally likely to agree with the statement ‘My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit’, however levels of agreement were higher among young people. People aged 15-24 were most likely to agree, at 70% for women and 69% for men. Men aged 45-54 showed the lowest levels of faith in recruitment and promotion decisions, with only 49% agreeing that they were fair and 35% disagreeing.

| Age | Gender | My organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit | |

| Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | ||

| 15-24 years | Women | 70% | 8% |

| 15-24 years | Men | 69% | 11% |

| 25-34 years | Women | 58% | 17% |

| 25-34 years | Men | 56% | 22% |

| 35-44 years | Women | 56% | 18% |

| 35-44 years | Men | 55% | 22% |

| 45-54 years | Women | 53% | 18% |

| 45-54 years | Men | 49% | 25% |

| 55-64 years | Women | 50% | 16% |

| 55-64 years | Men | 50% | 22% |

| 65+ years | Women | 56% | 11% |

| 65+ years | Men | 55% | 13% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

Older people were less likely to feel they had an equal chance at promotion in their organisations.

As Table 2.5 shows, although men were usually slightly more likely than women in the same age group to agree with the statement ‘I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation’, these differences were small. Both women and men in older age brackets were less likely to agree that they had equal chance at promotion, with only 40% of women 55+ and 40% of men 55+ agreeing with the statement. By contrast, 53% of women and 60% of men aged 15-24 agreed.

| Age | Gender | I feel I have an equal chance at promotion in my organisation | |

| Strongly agree or agree | Strongly disagree or disagree | ||

| 15-24 years | Women | 53% | 16% |

| 15-24 years | Men | 60% | 14% |

| 25-34 years | Women | 50% | 25% |

| 25-34 years | Men | 53% | 24% |

| 35-44 years | Women | 47% | 26% |

| 35-44 years | Men | 50% | 27% |

| 45-54 years | Women | 45% | 25% |

| 45-54 years | Men | 43% | 30% |

| 55-64 years | Women | 40% | 24% |

| 55-64 years | Men | 42% | 27% |

| 65+ years | Women | 40% | 17% |

| 65+ years | Men | 42% | 18% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents. ‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

‘Neither agree nor disagree’ and ‘Don’t know’ response options are not included in the table.

Flexible work practices

In all age groups, women were less likely to report working flexibly work than men.

As Table 2.6 shows, men were more likely to report flexible work arrangements than women in all age brackets. The largest discrepancy between genders can be seen in the 35-44 years and 45-54 years cohorts, where men reported flexible work arrangements 11 per cent higher than women in both brackets. Employees aged 25-54 were also more likely to report flexible work arrangements than employees in both older and younger age brackets.

| Age | Gender | PMS Respondents reporting flexible work |

| 15-24 years | Women | 19% |

| 15-24 years | Men | 20% |

| 25-34 years | Women | 23% |

| 25-34 years | Men | 30% |

| 35-44 years | Women | 27% |

| 35-44 years | Men | 38% |

| 45-54 years | Women | 22% |

| 45-54 years | Men | 31% |

| 55-64 years | Women | 19% |

| 55-64 years | Men | 25% |

| 65+ years | Women | 17% |

| 65+ years | Men | 22% |

Source: 2021 workplace gender audit data (People matter survey data) Notes: Total sample of 106,069 respondents.

Men selected ‘Flexible start and finish times’ as their most common type of flexible arrangement reported, regardless of age. Younger women (15-24 years) and older women (65+ years) were also most likely to choose this option, whereas women of all other ages (25-64) most often chose ‘Part-time’.

Discussion and conclusion

This chapter highlights the importance of considering the varied experiences and circumstances of women in the workplace at different ages. The 2021 workplace gender audit data analysed above shows that, consistent with previous research, gender is compounded with age in ways that negatively impact women’s safety and wellbeing at work, their career progression and to increase the gender pay gap.

For younger women, significantly higher rates of sexual harassment as compared to men in the same age brackets demonstrates how gender and age combine to increase the risk of harassment for younger women in the Victorian public sector. Fourteen per cent of women aged 15-24 reported the experience of sexual harassment and 11% of women aged 25-34 also did so. This compares to 4% and 5% respectively of men in the same age groups. The experience of sexual harassment for women in older age groups declined from 6% at age 35-44 years to 2% at 65+ years. For men, the experience declined from 4% at age 35-44 years to 2% at 65+ years. While the elimination of experiences of sexual harassment for everyone is very important, addressing this is a particularly urgent concern for women aged 15-34.

The Commission’s data also illustrates widening gaps between women and men over the life course in the areas of leadership and pay. A higher percentage of men report being in senior management and supervisory roles after 25 years of age, and this gap increases until age 55+. Evidence shows that gender- and age-based expectations contribute to the lack of women’s representation in leadership roles, with rigid and outdated expectations regarding women as primary carers for children and other family members restricting their career progression (Jones 2019; KPMG 2021).

Gender disparity in leadership opportunities is a contributing factor to the growing gender pay gap observed in older age brackets. Consistent with previous research (e.g. KPMG 2022), the Commission’s findings reveal the largest median base salary gender pay gap of any age group (13.2%, favouring men) occurs in the 55-64 age bracket. The gender pay gap favouring men increases in every age bracket from 25-34 to 55-64, before tapering off for employees 65 and over. The ramifications of these barriers faced by women in the progression of their careers, and in turn, their income, restrict their financial security and independence throughout their adult lives. They also contribute to the superannuation gender gap at retirement age. Australian women aged 60-64 have an average of 28% less super than men of the same age (KPMG 2021:14).

Overall, the compounding of age and gender inequality creates a range of challenges for women in the Victorian public sector, from pay and employment to caregiving responsibilities and ageism. Addressing these barriers will require a multifaceted approach that recognises the unique experiences and needs of women across their lifespan. Better childcare support, better workplace flexibility for all types of caring responsibilities, better designed jobs and valuing work-life balance, supporting workers through technological change through training and professional development, proactive workplace strategies to support workers with chronic health conditions to access paid employment, and addressing bias and discrimination in the workplace are all areas that require attention to ensure women can participate can access equal opportunities and outcomes throughout their lives (Chomik and Khan 2021; COTA 2022; Dangar et al. 2023; WGEA 2022).

Updated