Introduction

Gender bias can permeate every aspect of the recruitment and promotion lifecycle. Gendered language and imagery in job advertisements influence potential applicants, and unconscious and conscious bias and gendered stereotyping influence shortlisting, interviewing, hiring, salary and promotion decisions, as well as talent identification and performance and development discussions, programs, and opportunities.159

Gender-equitable recruitment and promotion practices are integral to achieving gender equality.160 Ensuring the recruitment, development, and promotion of a diverse workforce will ensure the organisations reporting under the Act are more representative of, and better equipped to serve, the diverse Victorian community. This will also enable the sector to model fair, flexible, and opportunity-filled career paths for people of all genders.

Key issues: Why was this measured?

Discrimination in recruitment and selection processes is pervasive

Gender-coded language and imagery in job advertisements can filter people into different occupations or industries.162

Conscious and unconscious bias in the processing of candidates’ information can lead to sub-optimal personnel decisions and discrimination among evaluators.163 Research has also shown that the CVs of women as well as minority groups are often unwarrantedly screened out in recruitment processes, particularly when these groups are underrepresented in specific industries or occupations.164

Compared to similarly qualified men, women receive fewer interview invitations, are perceived as less ‘hireable’ during recruitment and less ‘likeable’ when negotiating their salary, and are assumed to have lower levels of career motivation, therefore receiving fewer challenging work projects and development opportunities.165 As an example, research has found that women are more likely to leave STEMM careers compared to men due to the lack of mentoring and networks, as well as discrimination by managers and colleagues impacting on their career development opportunities.166

Intersectionality compounds gender discrimination

In a recent workplace survey conducted by Women of Colour Australia almost 60% of respondents reported that they had faced discrimination related to their identity as a woman of colour, including being passed over for promotion and having their ‘cultural fit’ raised as a reason they were less likely to be hired for the role.167

Similarly, women with disability report that they are not afforded the same employment and development opportunities as people without disability and are often disadvantaged by inaccessible recruitment practices and employer misconceptions about the cost of workplace modifications, equipment and concerns about additional human resources work.168

Recent research has found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are likely to be assigned or accept heavier unpaid cultural workloads (for example, by advising on Indigenous issues, initiatives, or content) than Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men.169 Mainstream research has found that additional and unpaid work assignments can be undervalued in comparison to traditional workloads and therefore form a contributing factor to slower promotion of women than men.170

Women also face growing barriers as they age, with research finding women are subject to negative age stereotypes about ‘employability’ from a younger age than men.171

Discrimination is a key driver of the gender pay gap

Discrimination in recruitment, salary negotiation, promotion and other development opportunities compounds across women’s careers and drives other forms of workplace gender inequality. For example, gender discrimination is the most significant driver of the gender pay gap172 and therefore impacts women’s economic security, as well as the overrepresentation of women in lower-level positions, as explored in the Equal pay and Workforce gender composition and segregation chapters of this report, respectively.173

Data on recruitment and promotion outcomes can reveal inequalities across the employment cycle within an organisation and help identify strategies to create more equal opportunities.

How was this indicator measured?

Organisations covered by the Act were asked to provide gender-disaggregated data on measures of recruitment and career progression over the period from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021.

The Commission used this data to calculate the proportion of men, women and gender diverse people in total recruitments, exits, promotions and career development opportunity uptake (including training, higher duties and internal secondments), disaggregated by employment basis and intersectional attributes.

In addition, employees of defined entities were invited to participate in a standardised employee experience survey. Organisations were surveyed separately, and the results were reported to the Commission as percentages of respondents. Items with fewer than 10 responses were suppressed to protect respondents’ privacy.

The Commission used this data to understand employee views about levels of support for diversity and inclusion, barriers to their success in the organisation, adequacy of learning and development opportunities, and fairness of organisational recruitment and promotion practices.

For the first time under Australian gender equality reporting legislation, organisations covered by the Act were required to provide data disaggregated not only by gender, but across a range of attributes. As outlined in the Introduction, we will publish insights from this intersectional data in our companion report on intersectionality, to be released in 2023.

Further detail about how each measure was defined can be found in the glossary at the end of this report.

What was found: Key data insights

Recruitments and exits by gender

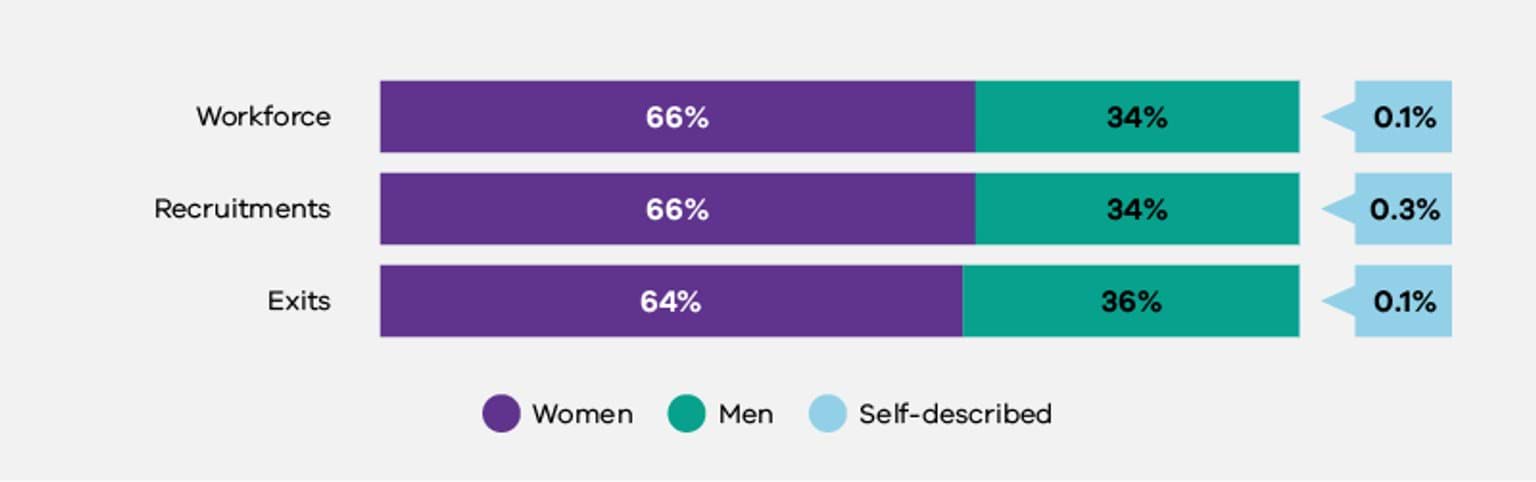

Recruitments and exits across organisations covered under the Act closely matched the gender balance of the workforce.

Between 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021, the proportion of staff that were recruited to work in, or that exited, organisations covered by the Act closely matched the gender balance of the workforce. Women made up 66% of the overall workforce and comprised 66% of recruitments and 64% of exits. People of self-described gender comprised a larger portion of recruitments (0.3%) compared to their proportion of the workforce (0.1%) and exits (0.1%).

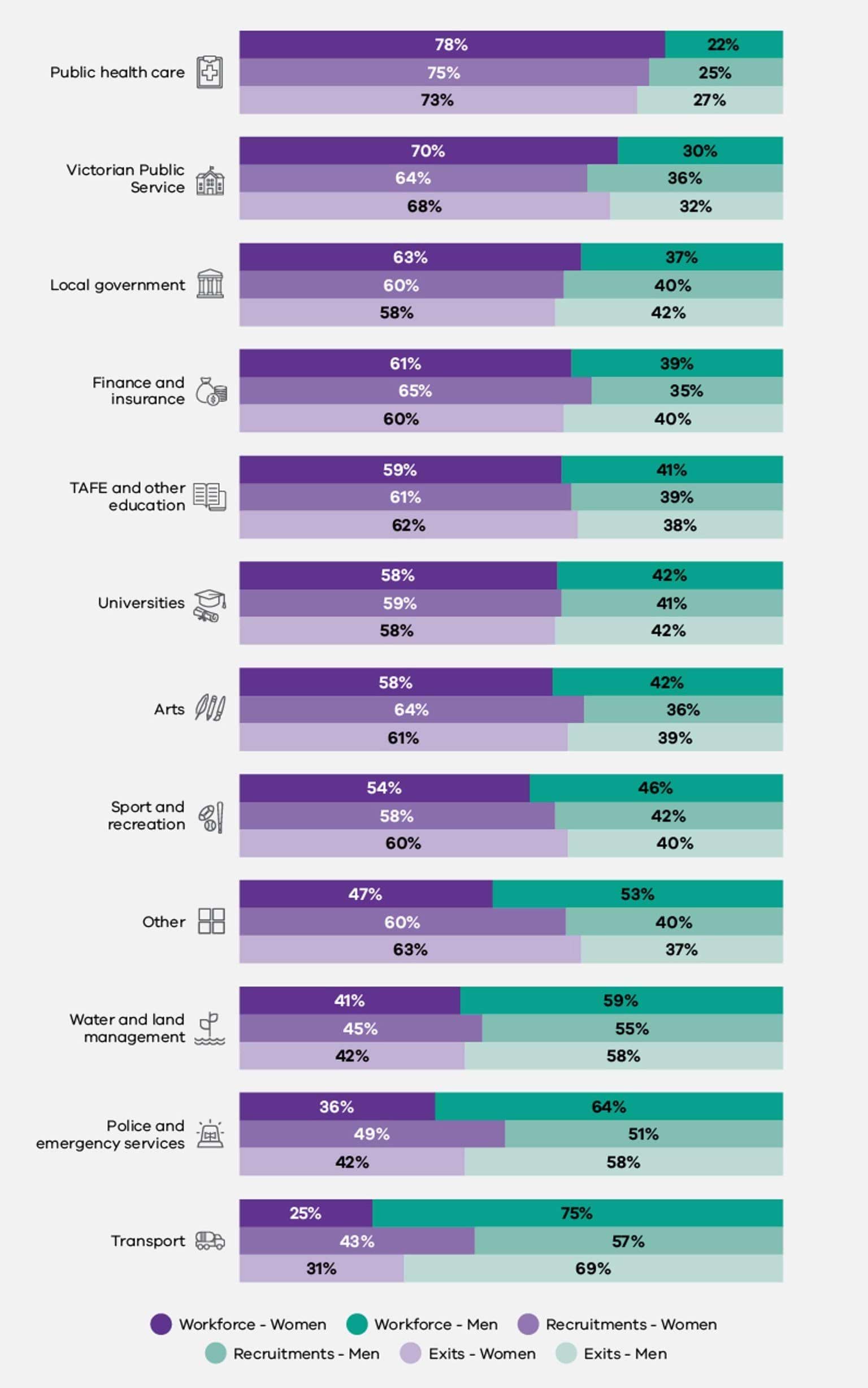

Recruitments and exits closely matched the gender balance of the workforce in most industry groups, as can be seen in Figure 4.2, below. The Transport industry group was the most significant exception, with women comprising only 25% of the workforce, but 43% of new recruits and 31% of exits.174

Some industries such as Transport, and Police and Emergency Services also experienced a higher proportion of men exiting organisations, relative to the number of men recruited over the same period. However, both the Transport and Emergency Services industries remain majority-men in composition.

Career development opportunities by gender

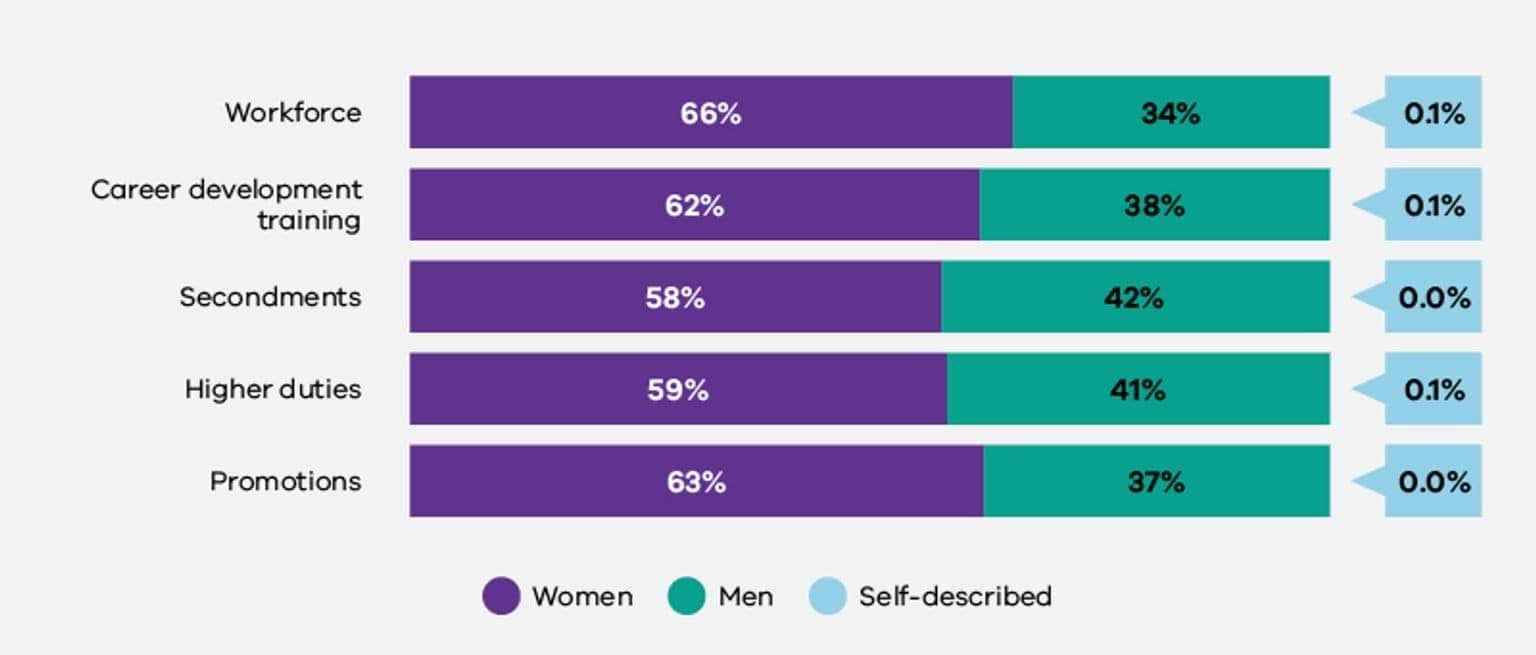

Despite making up 66% of the workforce across all defined entities, women comprised only 62% of those staff accessing career development training opportunities and only 58% of those awarded internal secondments. While men comprised 34% of the overall workforce, they made up 38% of those staff accessing career development training opportunities and 42% of those staff awarded internal secondments. People of self-described gender comprised 0.1% of people who accessed career development training and 0.1% of people who were awarded higher duties across all defined entities, which was comparable to their proportion of the total workforce.

This imbalance remained when it came to the proportion of staff awarded higher duties. Though they comprised 66% of the workforce across all defined entities, women comprised only 59% of staff awarded higher duties assignments and only 63% of those who received promotions. Whereas men comprised only 34% of the overall workforce, they were awarded 41% of higher duties awards and comprised 37% of those who received promotions.

Research from the US and the UK suggest this imbalance is not unique to the Commission’s data set. In the US, the Yale Insights 2021 study found that women are 14% less likely to be promoted each year.175 Similarly, McKinsey found that only 79 women are promoted to manager for every 100 men,176 and a UK study, found only 27.8% of women were promoted in the 3 years after childbirth, compared to 90% of new fathers.177

Views on recruitment and promotion by gender

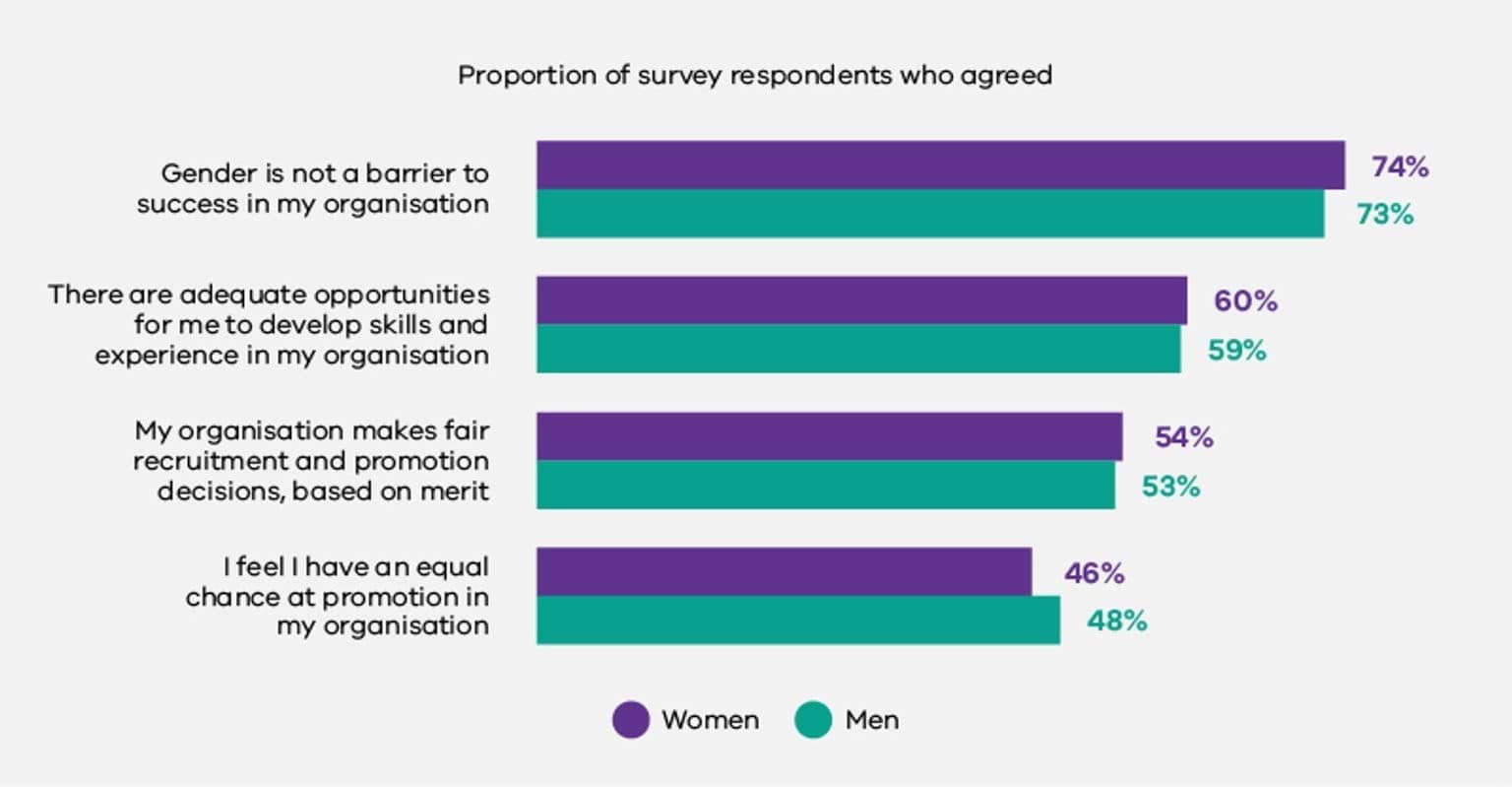

Among survey respondents, the responses from women and men in relation to recruitment and promotion practices were similar:

- nearly three-quarters of women and men felt that gender was not a barrier to success in their organisation

- more than half of women and men said there were adequate opportunities to develop skills and experience at work

- more than half of women and men agreed that their organisation makes fair recruitment and promotion decisions, based on merit

- just under half of women and men felt they had an equal chance at promotion in their organisation.

Discussion

Career progression is predicated on, among other things, ‘cumulative skill development’ and equal access to development opportunities – this means that when women are excluded from training opportunities, secondments and higher duties they experience vertical segregation in a workforce.178

The Commission’s audit data reveals that, while women were over-represented in the defined entity workforce as a whole (as explored in the Workforce gender composition and segregation chapter), they were under-represented in terms of access to career development opportunities. Further, men were disproportionately represented in higher-paying industries, occupations, and leadership classifications.

Each of these skewed distributions is influenced by inequalities in recruitment, promotion and career development processes and decision-making. For example, the Commission’s data revealed that women comprised only 45% of senior leadership roles and 38% of CEO roles across all defined entities, despite making up 66% of the workforce as a whole (see the Workforce gender composition and segregation chapter).

Women were also over-represented in Clerical and Administrative and Community and Personal Service Worker roles across defined entities. Not only did these occupations have the lowest median base salaries (aside from the Labourers occupation), but also had gender pay gaps in favour of men (see Figure 2.4 in the Equal pay chapter).

Women in defined entities were more than twice as likely than men to work in part-time roles across defined entities, while more than three‑quarters of those using flexible work arrangements were women (see Figure 1.2 in the Workforce gender composition and segregation chapter, and Figure 5.2 in the Leave and flexible work chapter).

Research shows that people in support roles (such as those in the Clerical and Administrative occupation group) tend to have decreased career enhancement, and that people working in flexible roles are more often overlooked for career development opportunities, such as training, promotion, and important meetings.179

Employee experience data analysed by the Commission demonstrated women in defined entities lacked confidence in their organisation’s recruitment and promotion processes. Only 46% of women respondents across defined entities felt like they had an equal chance of promotion in their organisation, while only 54% felt their organisation made recruitment and promotion decisions based on merit.

Merit and its attribution, however, are structured along perceived gender lines. Many organisations consider themselves to have ‘merit-based’ employment practices, whereby they employ and promote candidates based on their individual skills, traits, and qualifications, irrespective of gender or other attributes.

However, research commissioned by WGEA demonstrated that cultural assumptions and stereotypes can sway managers’ recruitment, selection, and promotion decisions.180 Research indicates that managers in organisations that explicitly claim to be meritocratic are more likely to exhibit gender biases in favour of men over equally qualified women.181

While it can be challenging for organisations to monitor the impact of a range of variables on individuals’ progression over the mid- to long-term, this information is crucial to ensuring organisations can track the impact of their interventions over time. Addressing unconscious bias and systemic discrimination in recruitment and promotion practices is key to achieving workplace gender equality.

As explained above, research indicates that employees from diverse backgrounds are more likely to experience discrimination and disadvantage at every stage of the employment cycle. This includes non-binary, gender-diverse and transgender employees and employees with intersectional attributes.182

For example, in Australia, the first national transgender mental health study in 2013 revealed that respondents had difficulty securing employment and faced discrimination in their workplace due to their transgender identity.183 In Canada, a survey of transgender individuals found that 18% of respondents had been denied a position because they were transgender and 13% had been dismissed from a role for being transgender.184

Similar results have been found in the UK and Ireland, where 35% of respondents believed they had not been hired for a position and further 19% experienced workplace harassment and discrimination at work because of their transgender identity.185 In the US, 67% of respondents to the 2015 US Transgender Survey who had applied for a position in the previous year reported not being hired, denied a promotion, or dismissed (constructively or expressly) as a result of their transgender identity.186

The Commission requested that defined entities submit a broad range of intersectional data in this first workplace gender audit cycle. This included data in relation to recruitment, retention and promotion for gender-diverse people, as well as people with a range of other intersectional attributes. Due to a number of factors – including that many defined entities currently lack system configurations that enable collection of this data – there remain significant data gaps in this area.

Workforce gender audit data reveals that 0.1% of people who accessed career development training and 0.1% of people who were awarded higher duties across all defined entities were people of self-described gender.

In future years and following release of the Commission’s findings and recommendations on intersectionality in 2023, defined entities will be able to develop their capacity to provide more complete data in relation to intersectional gender inequality in recruitment, promotion, and career development opportunities.

Recommendations

Organisations that are leading on gender equality recognise that their recruitment and selection strategies must be accompanied by regular and consistent monitoring and evaluation processes. This is important to establish the level of progress against their goals for more gender-equal recruitment and selection.187

In these leading practice organisations, monitoring and evaluation of performance on gender equality outcomes is considered throughout the recruitment, selection and onboarding processes for new employees.188 Data is then used to help inform and guide actions if inequalities are identified.189

Some organisations have also begun to extend their evaluation into career development processes, such as promotions and performance and development reviews. Metrics that support these evaluation processes include data related to development opportunities, allocation and distribution of higher duties, and approvals for professional development leave.190

Data collected as part of the 2021 workplace gender audit showed that while organisations covered under the Act provided a wide variety of formal and informal career development and training opportunities, there are inadequate systems in place to monitor access and take-up, particularly among intersectional cohorts.

This data can be collected through learning and development systems, as well as through regular anonymous pulse surveys that include an optional demographic component to capture informal opportunities.

References

- I Bohnet, What Works: Gender Equality By Design, Harvard University Press, 2016; Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), Gender equitable recruitment and promotion, 2019, accessed 25 July 2022.

- WGEA, Gender equitable recruitment and promotion.

- M Adamovic, ‘Analyzing discrimination in recruitment: A guide and best practices for resume studies’ International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 2020, 28(4), pp 445-464, doi:10.1111/ijsa.12298.

- D Gaucher, J Friesen, and AC Kay, ‘Evidence That Gendered Wording in Job Advertisements Exists and Sustains Gender Inequality’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, July 2011, 101(1):109-28, doi:10.1037/a0022530.

- A Genat, Evaluation bias and backlash: how unconscious gender bias hurts women's career progress and two interventions to improve outcomes [doctoral dissertation], The University of Melbourne, 2019, accessed 25 July 2025.

- Adamovic, ‘Analysing discrimination in recruitment’.

- WGEA, Gender ethical recruitment and promotion.

- J Hunt, ‘Why do women leave science and engineering?’, ILR Review, 2016, 69(1):199-226, doi:10.1177/0019793915594597; Professionals Australia, Women staying in the STEM workforce - an economic imperative for Australia: Professionals Australia's Women in the STEM Professions Survey Report [PDF 3.42MB], Professionals Australia, 2021, accessed 29 August 2022.

- Women of Colour Australia (WoCA), Workplace Survey Report 2021, WoCA, 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Women with Disabilities Australia (WWDA), WWDA's Submission to the National Disability Employment Strategy Consultation Paper, 2021, accessed 25 July 2022; Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC), Willing to Work: National Inquiry into Employment Discrimination Against Older Australians and Australians with Disability, 2016, accessed 25 July 2022.

- O Evans, Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): gendered insights, Jumbunna Institute of Education and Research and Diversity Council Australia, 2021, accessed 22 July 2022, p 7.

- Evans, Gari Yala.

- M McGann et al., ‘Gendered Ageism in Australia: Changing Perceptions of Age Discrimination among Older Men and Women’ Economic Papers (Economic Society of Australia), 35(4):375-388, doi:10.1111/1759-3441.12155.

- KPMG, She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap, KPMG, 2022, accessed 22 July 2022.

- WGEA, Women’s economic security in retirement, 2020, p 12, accessed 25 July 2022; KPMG, She’s Price(d)less.

- There was insufficient data in this measure to report meaningfully on the experiences of people of self-described gender.

- Chief Executive Women, Take It from the Top: Accelerating Women’s Representation in Executive Leadership [PDF 1.65 MB], 2022, p 17, accessed 25 July 2022.

- McKinsey & Company, Women in the Workplace 2021, 27 September 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- University of Bristol, Women ‘less likely to progress at work’ than their male counterparts following childbirth [press release], University of Bristol, 2 October 2019, accessed 25 July 2022.

- T Fitzsimmons et al., Employer of Choice for Gender Equality: Leading practices in strategy, policy and implementation, AIBE Centre for Gender Equality in the Workplace, 2020, p 127, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Fitzsimmons et al., Employer of Choice for Gender Equality, p 67.

- WGEA, Gender equitable recruitment and promotion.

- EJ Castilla and S Bernard, ‘The Paradox of Meritocracy in Organizations’ Administrative Science Quarterly, 2010, 55(4): 543-676.

- S Waite, ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go? Employment Discrimination and Workplace Harassment against Transgender and other Minority Employees in Canada’s Federal Public Service’, Journal of Homosexuality, 2021, 68(11):1833-1859, doi:10.1080/00918369.2020.1712140; KK Dray et al., ‘Moving beyond the gender binary: Examining workplace perceptions of nonbinary and transgender employees’, Gender, Work & Organisation, November 2020, 27(6):1181-1191, doi:10.1111/gwao.12455; LK Kleintop, ‘Deciding to be Authentic: Transgender Employees and Their Decision to Be Out at Work,” in J Marques (ed) Exploring Gender at Work, Springer, 2021), pp 139-158, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-64319-5_8.

- Z Hyde et al., The First Australian National Trans Mental Health Study: Summary of Results, Curtin University of Technology: School of Public Health, 2013, accessed 25 July 2022.

- GR Bauer and AI Scheim, Transgender people in Ontario, Canada: Statistics from the Trans PULSE project to inform human rights policy, Trans PULSE Project Team, 2015, accessed 25 July 2022.

- J McNeil et al., Trans Mental Health Study, 2012, p 96, accessed 25 July 2022.

- S James et al., The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey [PDF 2.21 MB], National Centre for Transgender Equality, 2016, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Fitzsimmons et al., Employer of Choice for Gender Equality.

- Fitzsimmons et al., Employer of Choice for Gender Equality.

- Fitzsimmons et al., Employer of Choice for Gender Equality.

- Fitzsimmons et al., Employer of Choice for Gender Equality.

Updated