- Date:

- 5 Sep 2022

This Baseline report provides an overview of the current state and nature of gender inequality across the span of organisations reporting for the first time under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (Act).

It will assist the Commission, defined entities, and the Victorian community to understand:

- where the challenges and gaps are to progressing gender equality

- where to focus efforts to improve.

It will provide a starting point from which to:

- track change against each indicator

- determine if reasonable and material progress is being made

- identify areas where the development of targets and/or quotas under the Act could drive greater progress.

Acknowledgement of Country

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector acknowledges and pays respect to the Traditional Owners of the lands on which we are proud to be located. Our office is based on the lands of the Wurundjeri people – the lands on which many of our team members also live and work from home. Other team members live and work on Bunurong land and Dja Dja Wurrung land.

We also acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of Country throughout Victoria and pay our respects to them, their cultures, and their Elders past and present. We recognise the deep and enduring connection of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples to Country and their continuing custodianship of the land, waterways and seas.

We proudly recognise the First Nations peoples as having the world’s oldest living cultures, and acknowledge that the heritage, traditions and customs of Aboriginal communities throughout Victoria are vibrant, rich and diverse. We value this knowledge and consider it a source of strength and opportunity.

We respect that Elders and other leaders of Aboriginal communities in Victoria are critical to redressing inequality and disadvantage and improving outcomes for Victorian women. Their leadership includes First Nations women, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, non-binary, sistergirls, brotherboys, intersex and queer folk who drive gender equality across Victoria. We thank them and honour their important work.

As we reflect on the continuing impact of government policies and practices, we recognise our responsibility to collaborate and work together with First Nations peoples, families and communities towards improved economic, social and cultural outcomes.

Message from the Commissioner

Message from the Commissioner

As Victoria’s inaugural Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner, I am pleased to be delivering this report analysing the Commission’s workplace gender equality data. Data was collected for the first time in late 2021 from almost 300 organisations covered by the Gender Equality Act 2020. This Baseline report provides a sector-wide overview of the state and nature of workplace gender inequality and will serve as the starting point against which to measure future progress.

I want to commend the hard work of all the staff who supported their organisations to meet their obligations under the Act, as well as my own small (but mighty) team at the Commission. The collection and analysis of this data represents a significant milestone in gender equality reporting in Australia; one that was achieved while also contending with the challenges and uncertainty brought about by COVID-19. The pandemic disrupted the implementation of the Act in many ways. At the same time, it widened the national gender pay gap and reversed or stalled progress made towards gender equality on several fronts. Therefore, it is more important than ever that we keep driving action to promote gender equality.

As in any new process, there is significant learning to be incorporated into future workplace audit reporting rounds to improve clarity, efficiency, and impact. In particular, there is work to be done to better understand and address how other forms of disadvantage and discrimination intersect with gender inequality. My team and I are committed to building this evidence base and capability. To support this, we will release a separate report in early 2023, which will present intersectional insights from the audit data, along with insights and recommendations from the intersectional research we have commissioned this year.

There are also improvements to be made in terms of resourcing the work required to meet the obligations under the Act. A study we commissioned in 2021 found that many entities had delegated the audit and planning work to women at lower levels of their organisations who were employed on a temporary basis, with little consideration of ongoing resources to support implementation. I acknowledge that many organisations were operating in a challenging environment and that there are always lessons learnt the first time such ambitious work is undertaken. However, the Act requires that organisations ensure adequate resourcing is set aside to implement the obligations, including to demonstrate the ‘reasonable and material’ progress that is required every 2 years.

We’re at a critical juncture for gender equality in Australia. Yet, there is a lot to be optimistic about. This baseline report shows that organisations covered by the Act are performing well in comparison to the private sector across many gender equality outcomes, and while there is still much progress to be made, it is very clear that there is a real appetite for change. In this first cycle of reporting, defined entities have repeatedly demonstrated their commitment to progressing gender equality, with many engaging passionately with me and my team to ensure they achieve the best gender equality outcomes possible.

I want to acknowledge all the work that has been done to get us to the point where we now have this nation-leading baseline data. I am confident that Victoria will continue to lead by example in addressing the systemic drivers of gender inequality within the workforce, and in inspiring other jurisdictions on the road towards gender equality in their organisations and communities.

I look forward to continuing to work with organisations to assist them in driving meaningful progress toward workplace gender equality.

Dr Niki Vincent

Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner

Executive summary

A summary of the key findings from the analysis of audit data collected under the Gender Equality Act 2020 in 2021.

Driving gender equality through the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic)

Under the Gender Equality Act 2020 (Vic) (the Act), organisations covered by the Act – known as defined entities – are subject to a number of obligations that require them to take positive and transparent action towards achieving gender equality in their workplaces and in their public policies, programs and services.

The elements of the Act that embed this transparency and progress towards gender equality are part of what makes this legislation nation-leading.1 While comparable legislative frameworks nationally or around the globe may require the submission of gender equality data, most do not require organisations to publish their data, develop action plans to address any inequalities revealed in the data, or make reasonable and material progress to promote gender equality in every 2-year period.2

The Commission is committed to supporting defined entities to meet their obligations under the Act through improved training, education, and guidance resources. This baseline report of workplace gender audit data and the Commission’s upcoming in-depth analysis of each organisation’s Gender Equality Action Plan (GEAP) and companion baseline report on intersectional analyses, will help the Commission understand how to tailor its support in future years. It will also help defined entities understand what actions they need to take to embed systems and processes that support full and effective compliance with the Act.

The Commission acknowledges the effort and dedication of the people in defined entities across the state who have undertaken this important work, many for the first time. We recognise the powerful contribution this will make towards achieving gender equality in defined entities and the broader Victorian community.

Establishing the baseline for ongoing progress

This Baseline Report covers the key findings from the inaugural workplace gender audit data collected under the Act in 2021.

Establishing how defined entities are tracking towards workplace gender equality is crucial to ensuring we can build on the gains we have already made in the public sector. Synthesising these results is also vital to support the sector to address persistent blockers of, and accelerate progress towards, gender equality.

It is important to recognise that this is the first time that defined entities have been required to conduct a workplace gender audit. As such, the audit has revealed areas of limited data availability and poor data quality (particularly in relation to intersectional data).3 Where existing processes did not allow for the collection of sufficient data, or did not yet exist, organisations were asked to specify how they would rectify this as part of their GEAPs. Similarly, the Commission will work to improve its systems and support entities to improve their systems, in order to improve data quality over time. A process evaluation will be undertaken to identify areas for improvement and ensure greater efficiency and quality in future reporting rounds. Specific recommendations for actions to improve data quality are included throughout this report.

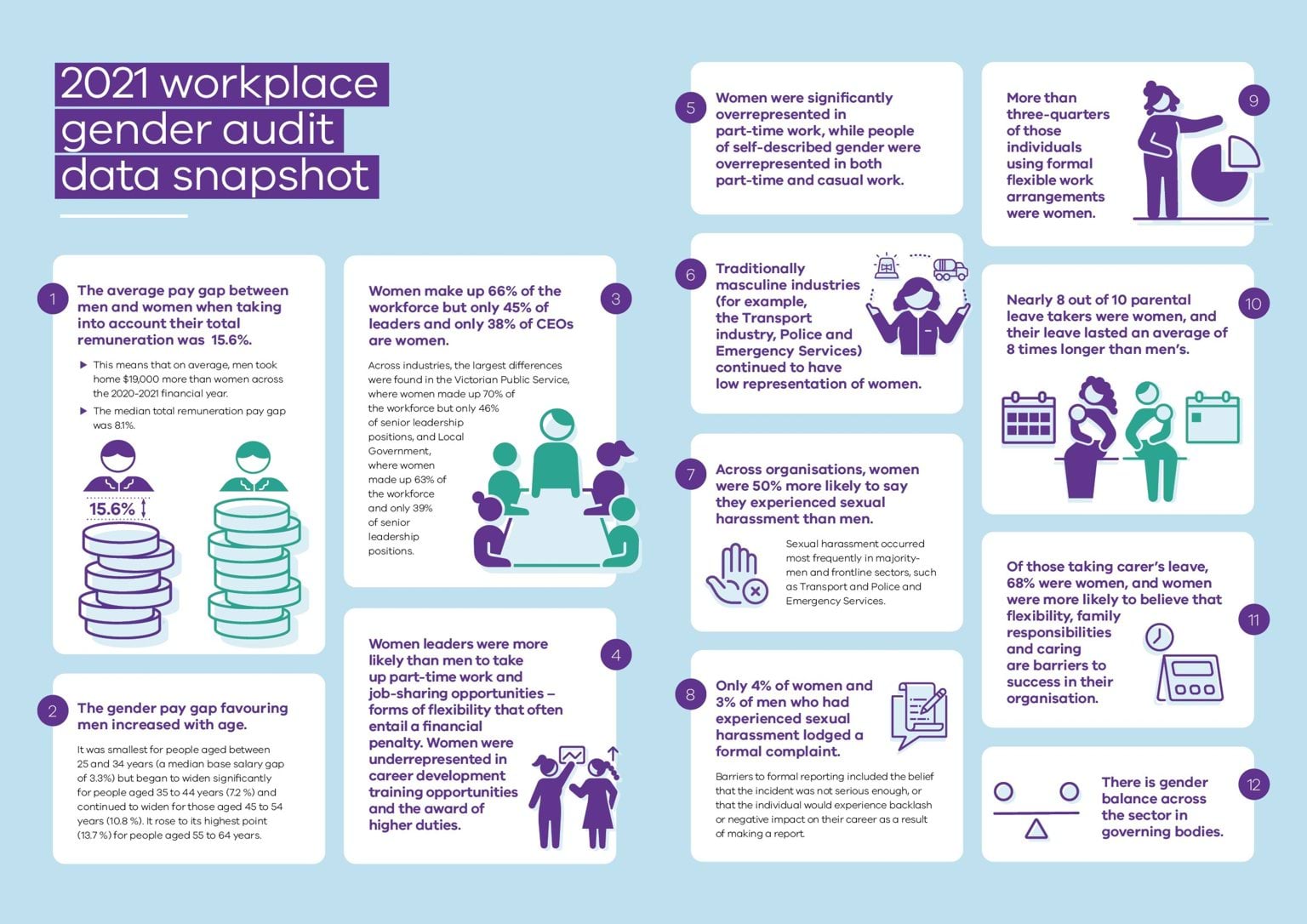

The gender pay gap

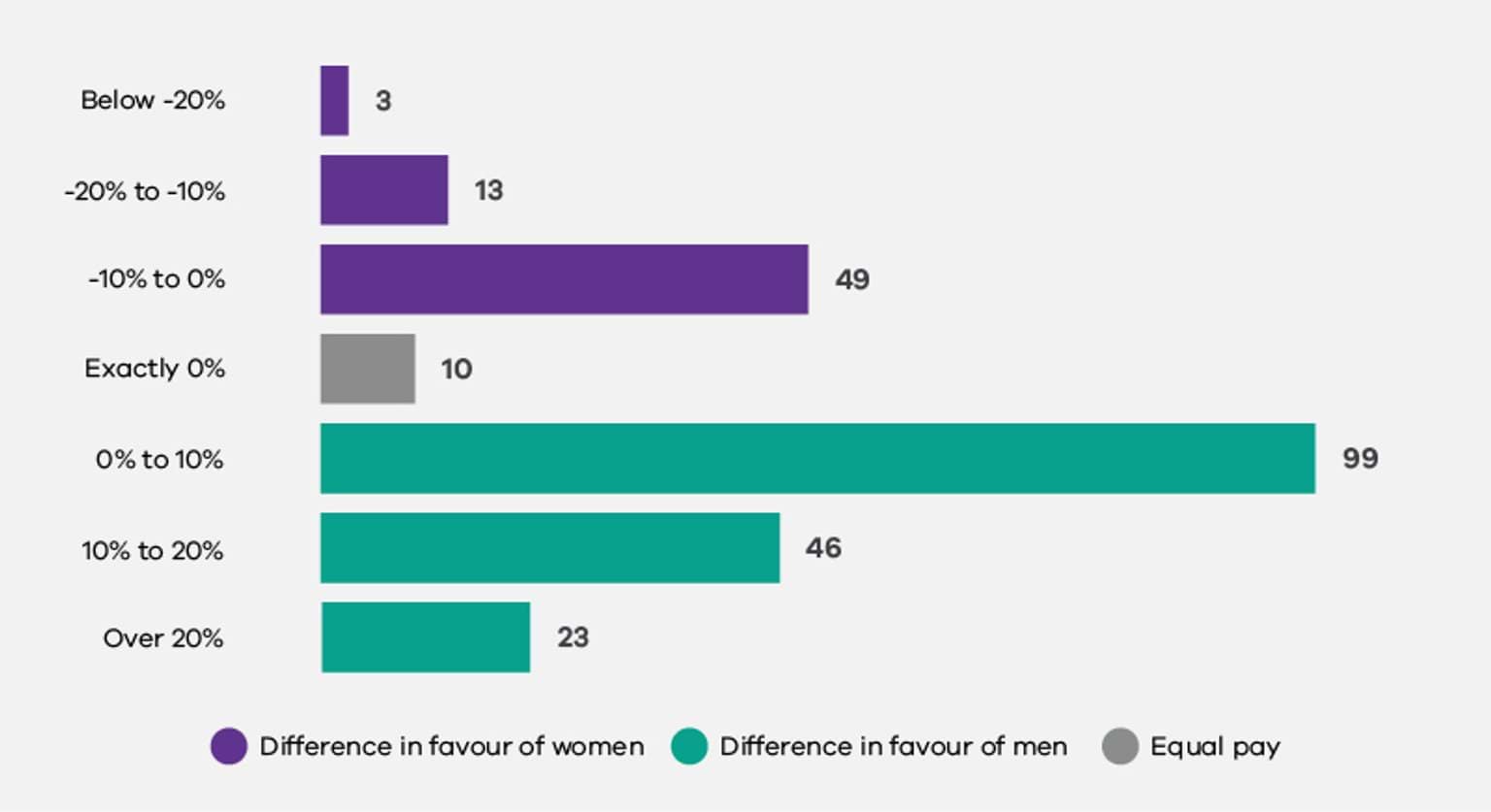

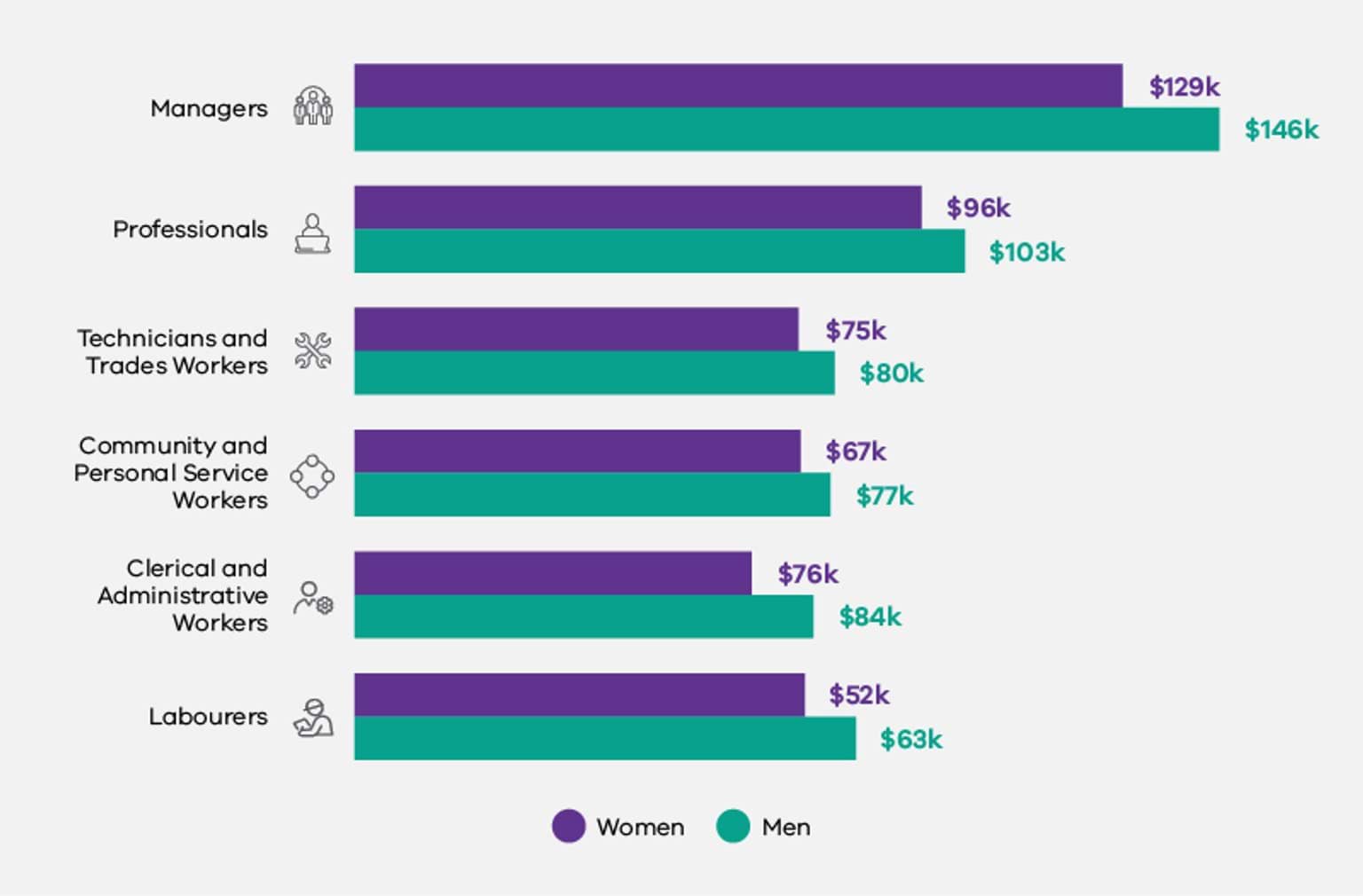

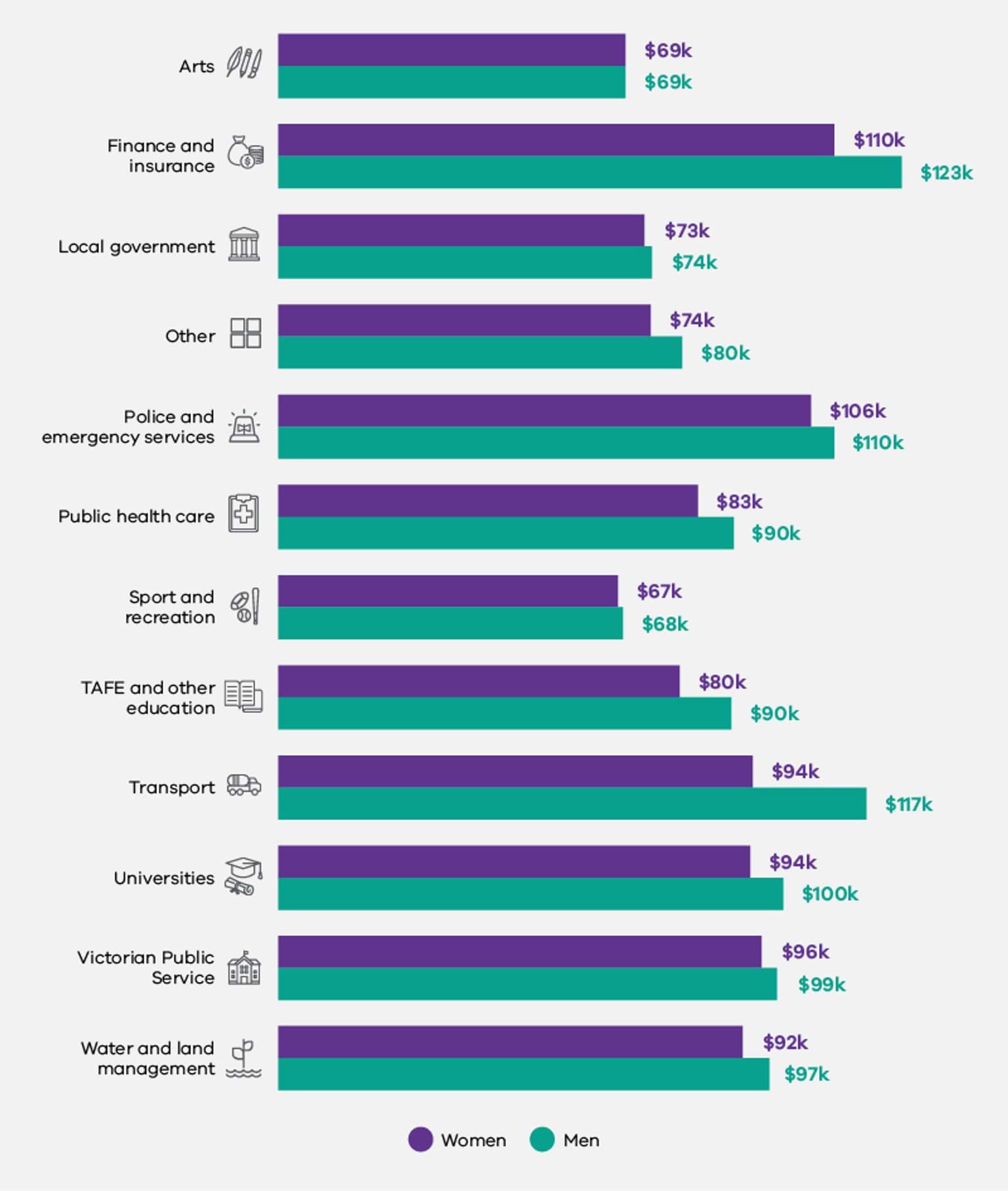

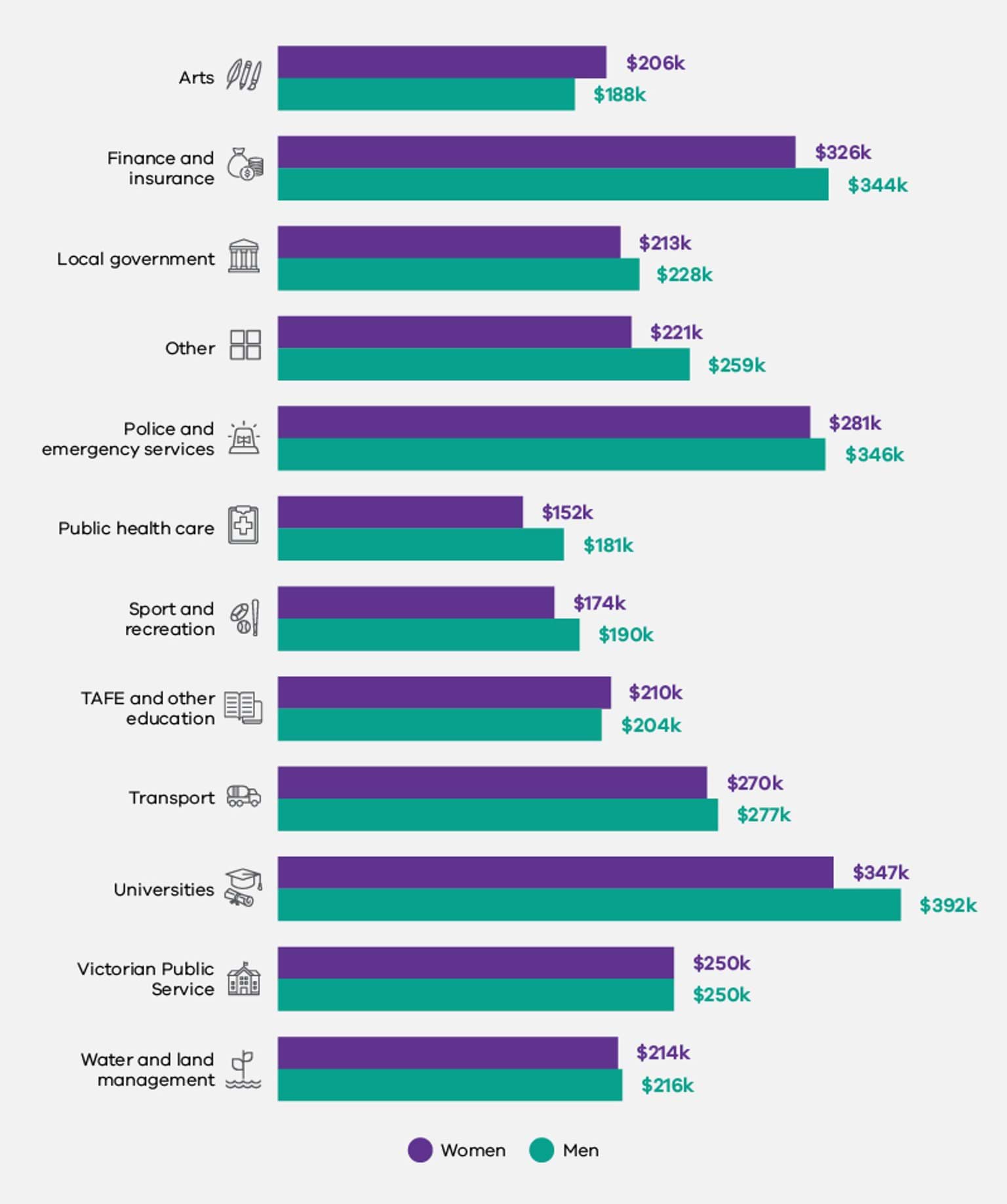

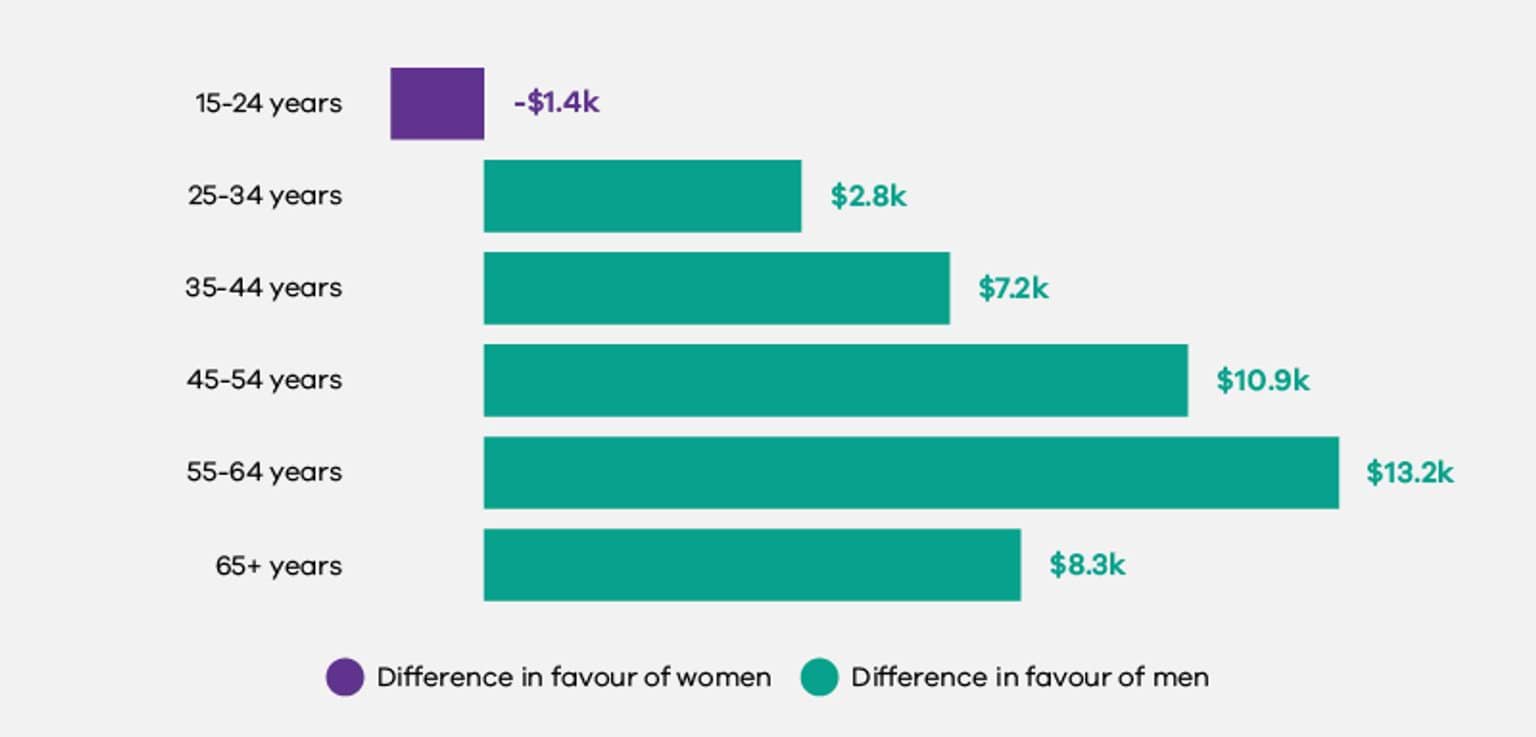

Across all the organisations covered by the Act, the average pay gap between men and women when taking into account their total remuneration was 15.6%. This means that on average, men took home $19,000 more than women across the 2020–2021 financial year. The median total remuneration pay gap was 8.1%.

In comparison, in the private sector, Australia’s national total remuneration gender pay gap was 22.8% or $25,792, as calculated by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

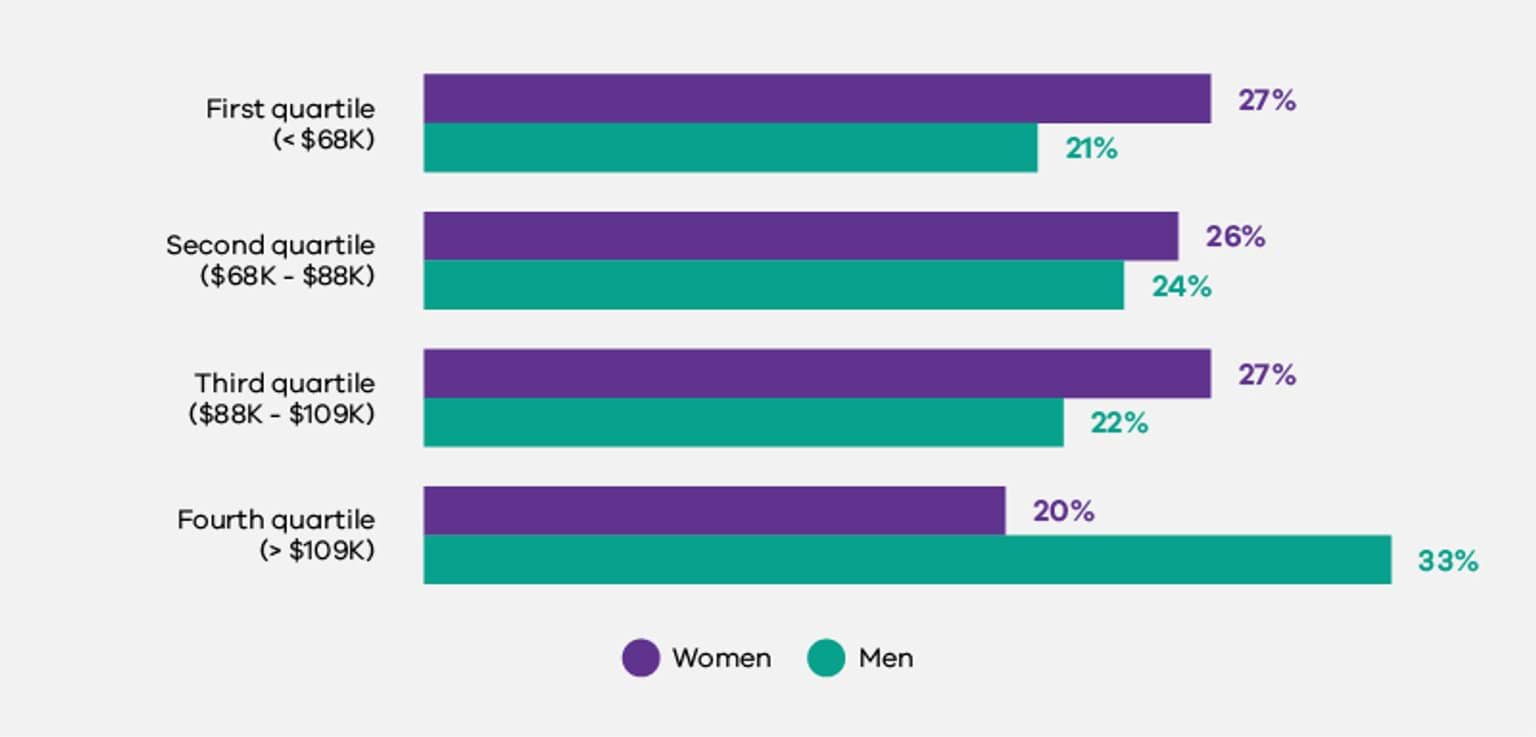

While it is encouraging to see organisations reporting under the Act doing better than the private sector when it comes to equal remuneration, there is still a very significant gap to close. Pay gaps existed in favour of men across all occupational groups (except at the CEO level) among defined entities. This supports existing research that the constellation of gender inequalities and biases that combine to create the gender pay gap operate across different jobs and is not a result of stereotypically ‘masculine’ occupations alone.

Part-time work

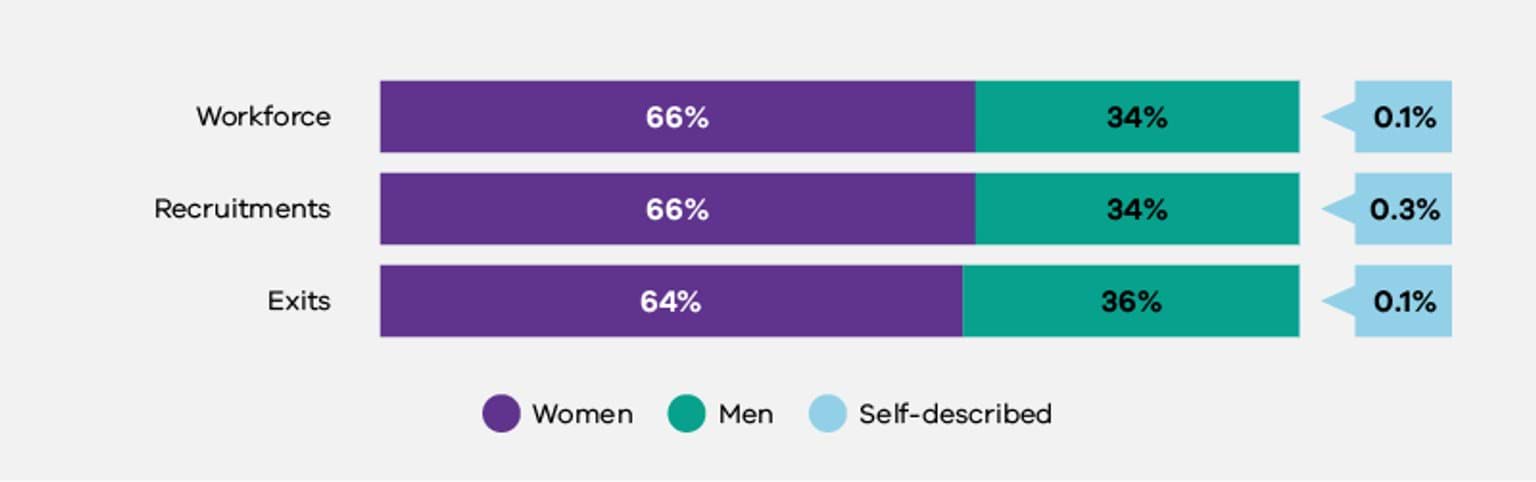

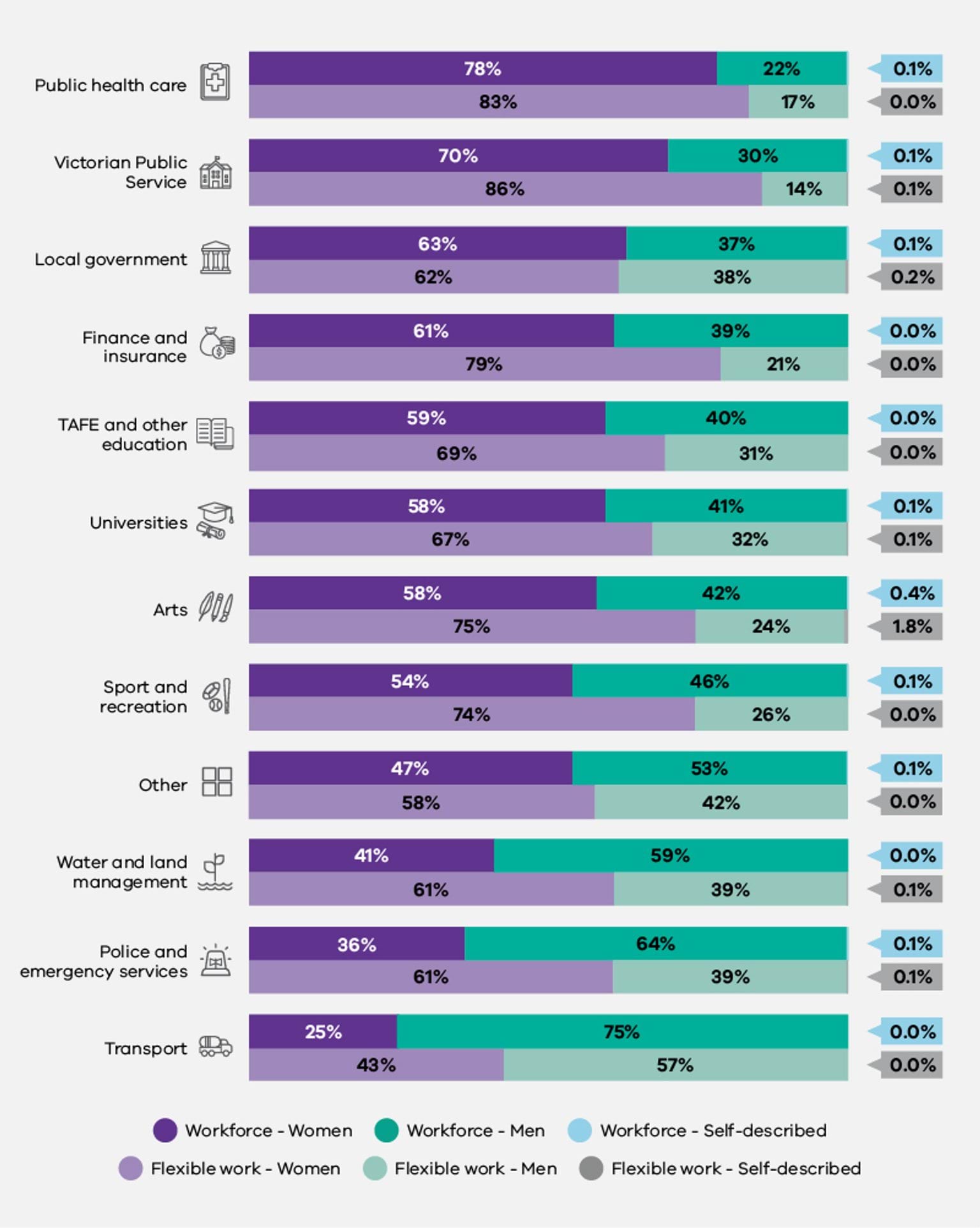

Women experienced strong representation across organisations covered by the Act, comprising 66% of all employees. However, this representation masks persistent inequalities. Most notably, when we drilled down into employment type, significant imbalances emerged. Women were significantly overrepresented in part-time work, while people of self-described gender were overrepresented in both part-time and casual work. Traditionally masculine industries (for example, the Transport industry, Police and Emergency Services) continued to have low representation of women.

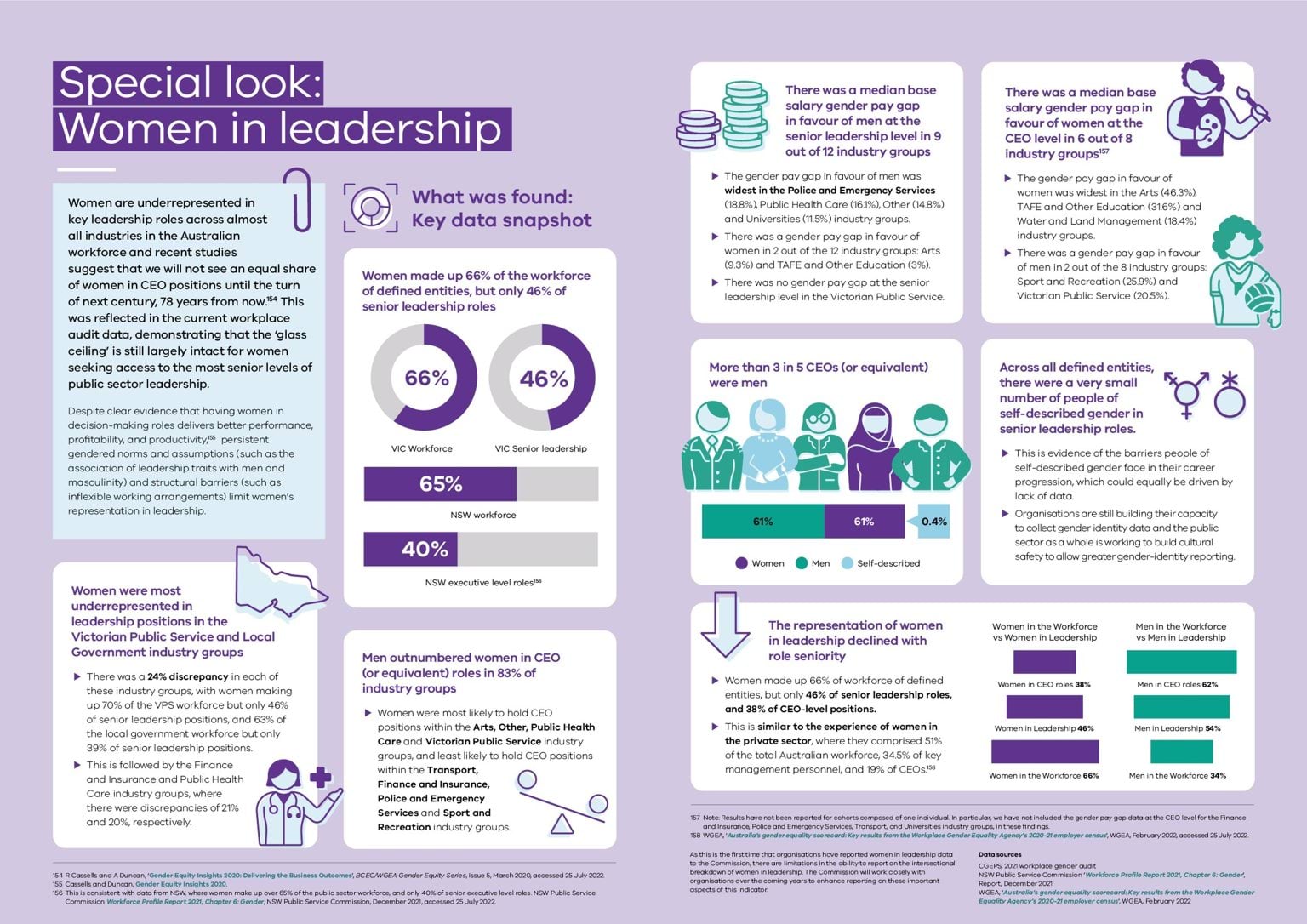

Leadership

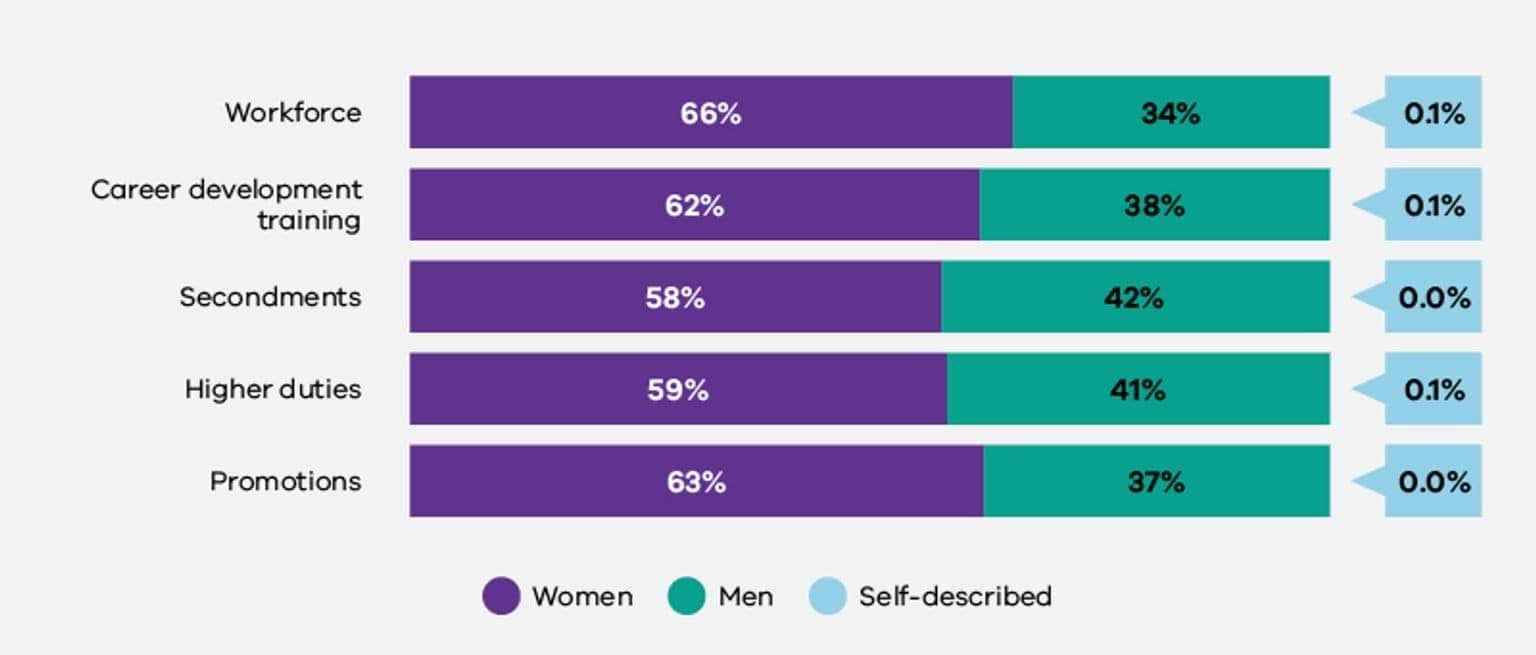

While women comprised 66% of the total workforce, only 45% of those in senior leadership roles were women and more than 3 in 5 CEOs were men. Women were also underrepresented in career development opportunities, training, and the award of higher duties.

Encouragingly, there was a gender balance between men and women on the boards of defined entities, which has been supported through Victorian Government targets introduced in 2015.

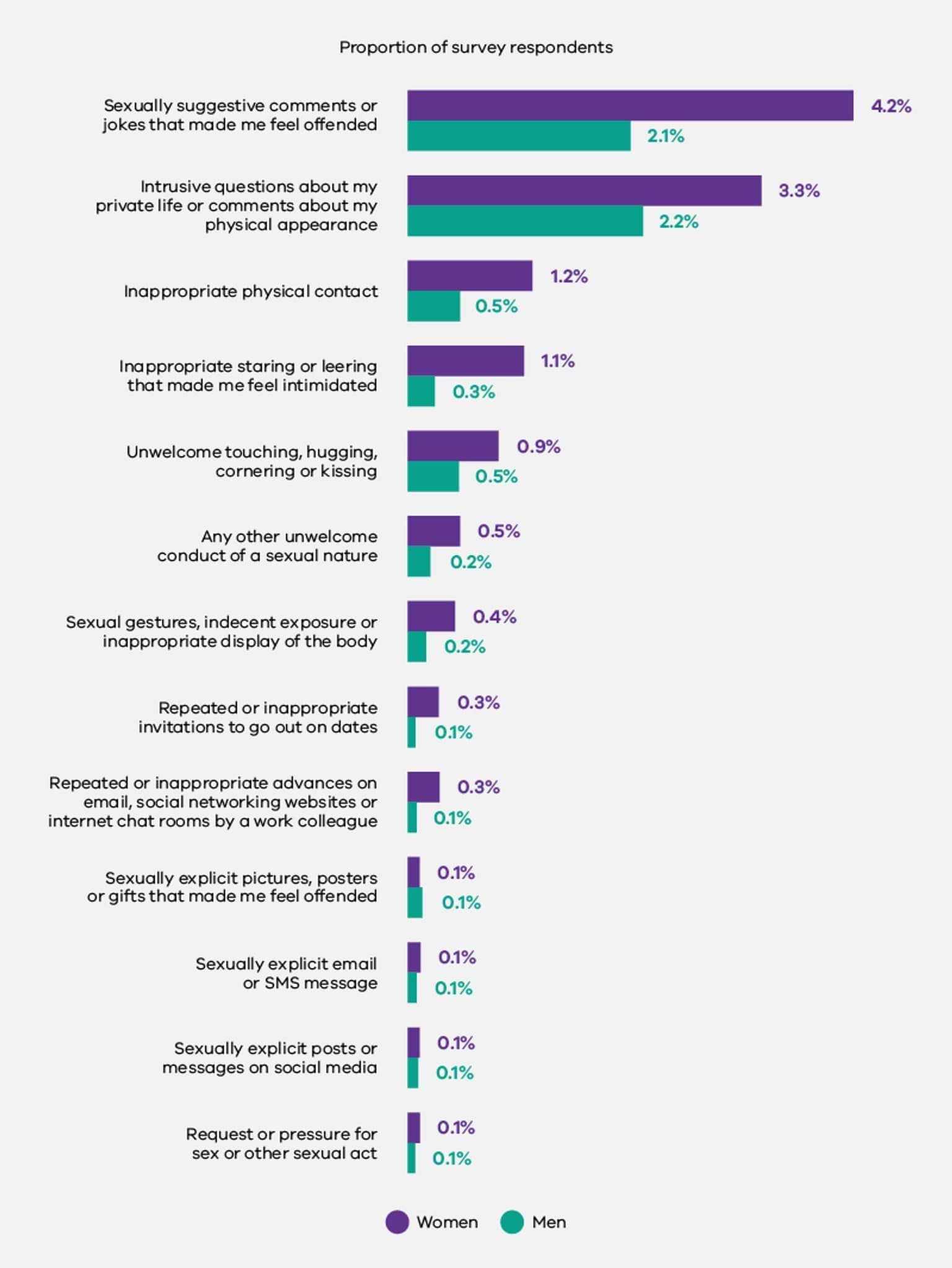

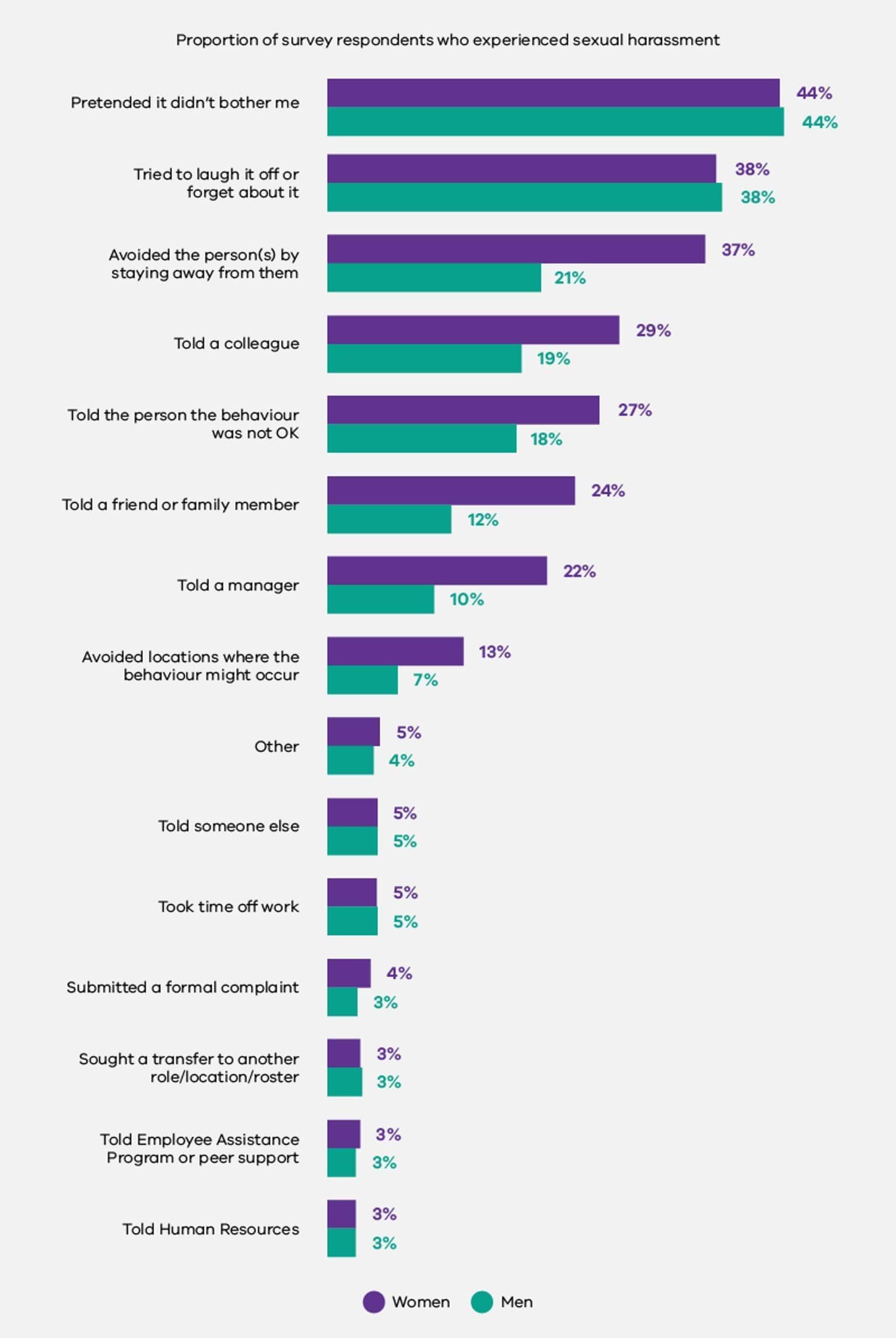

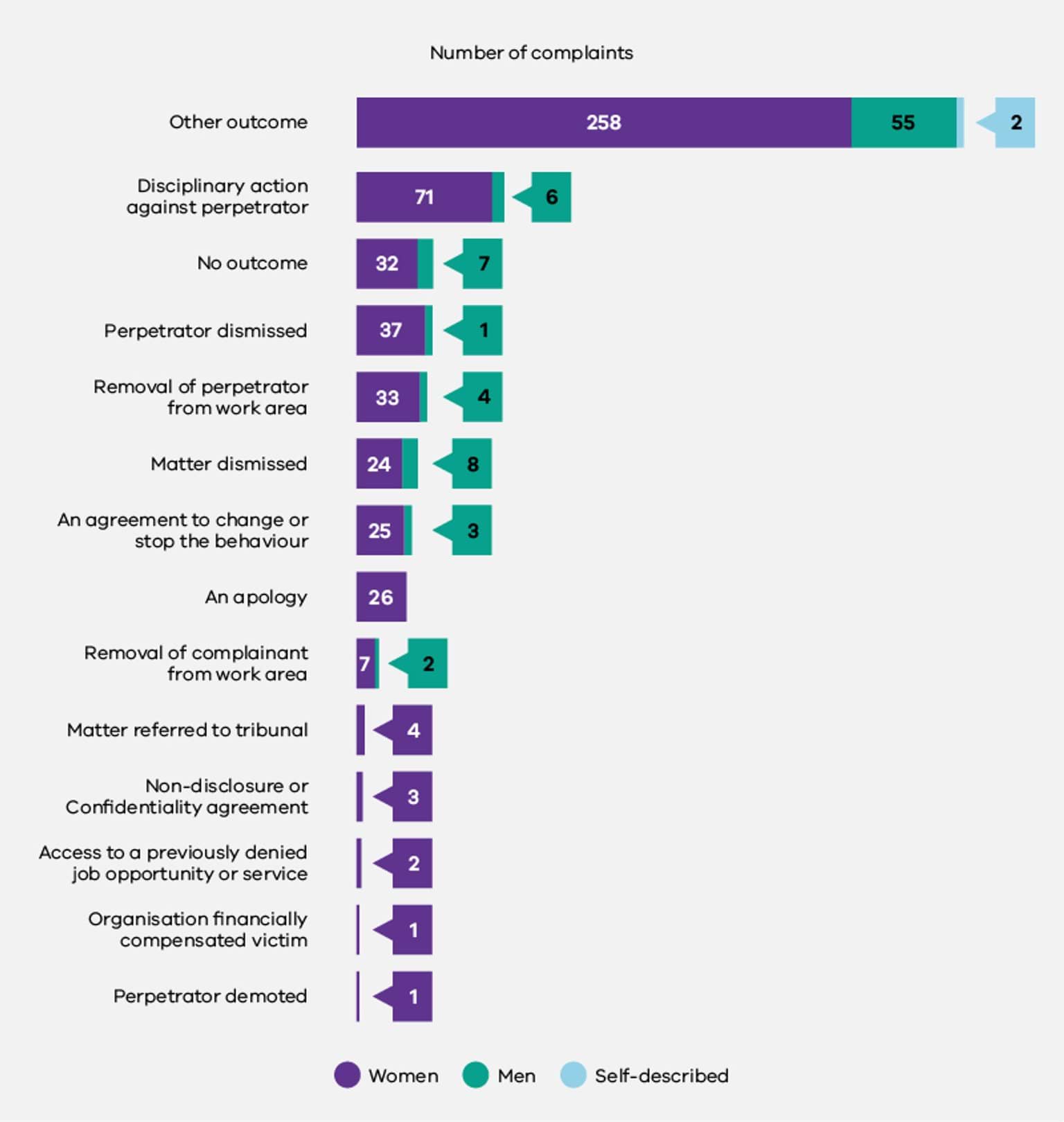

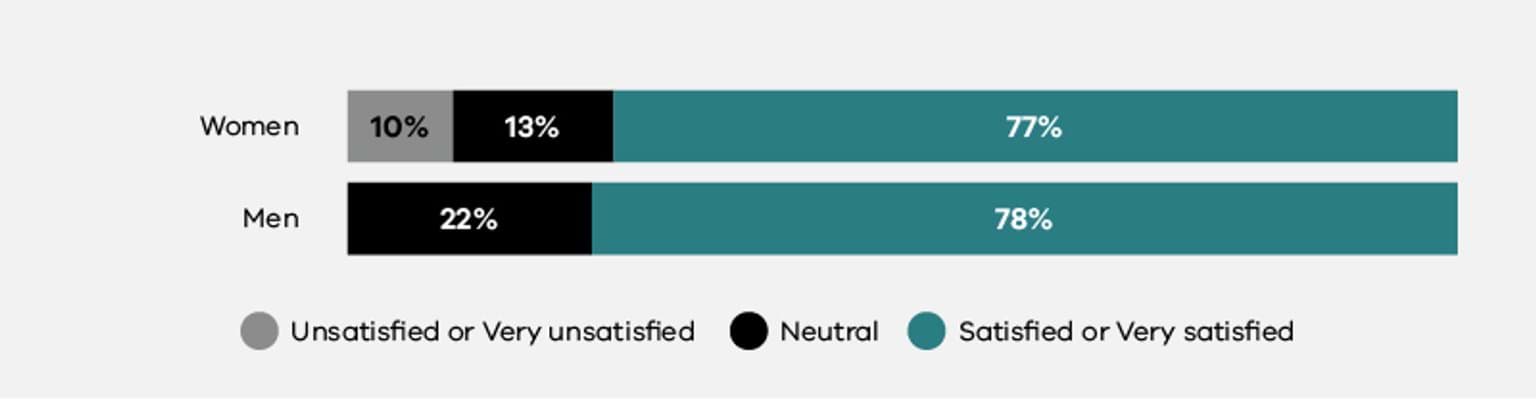

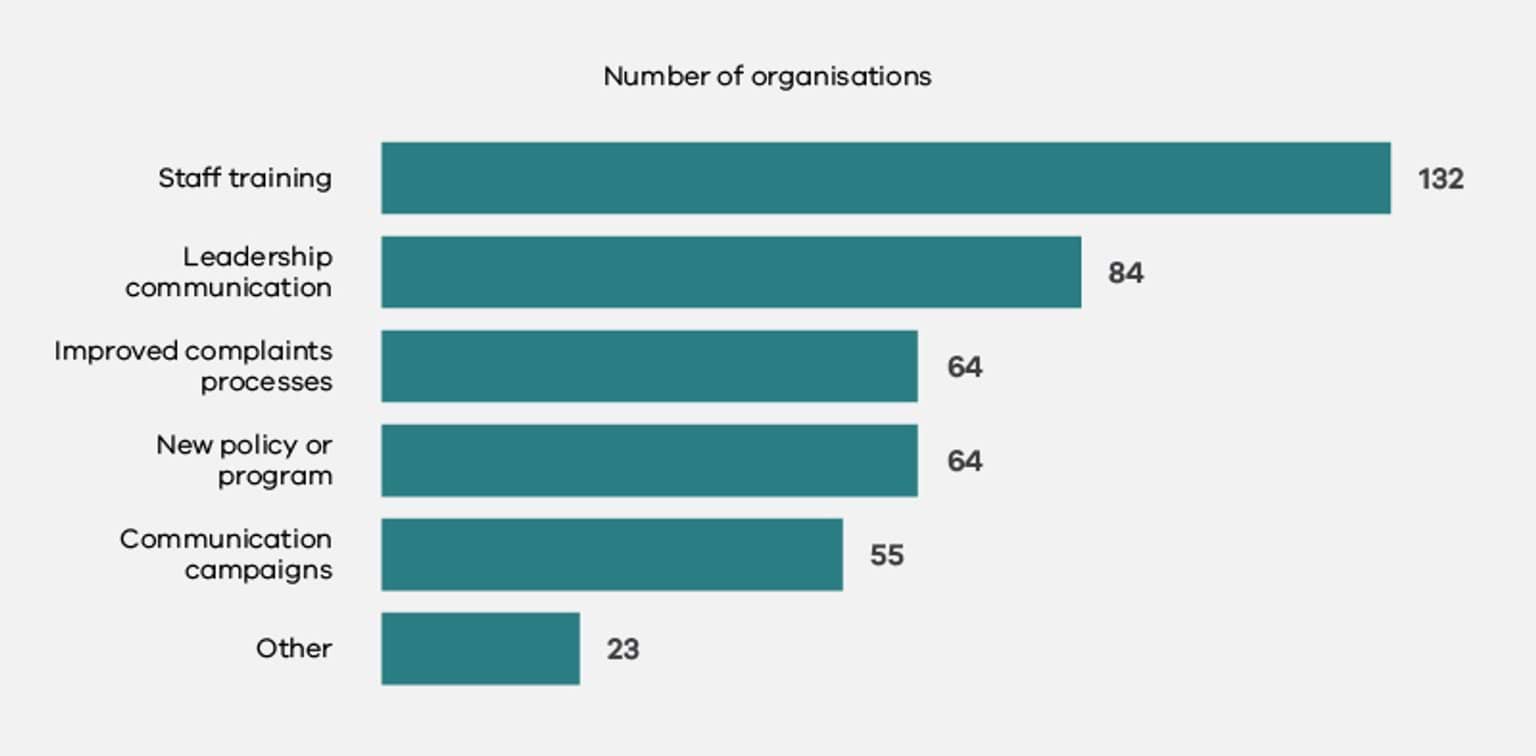

Sexual harassment

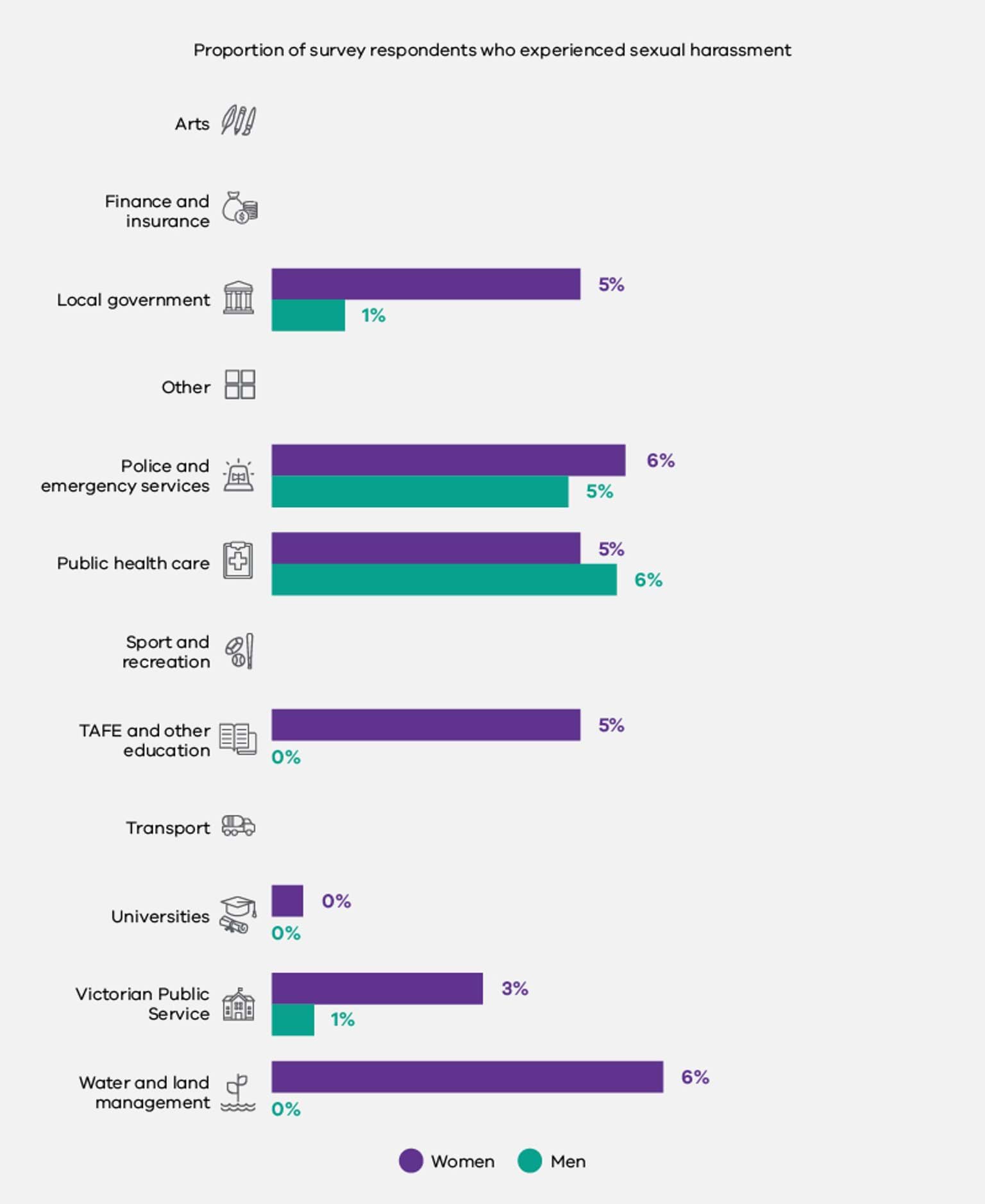

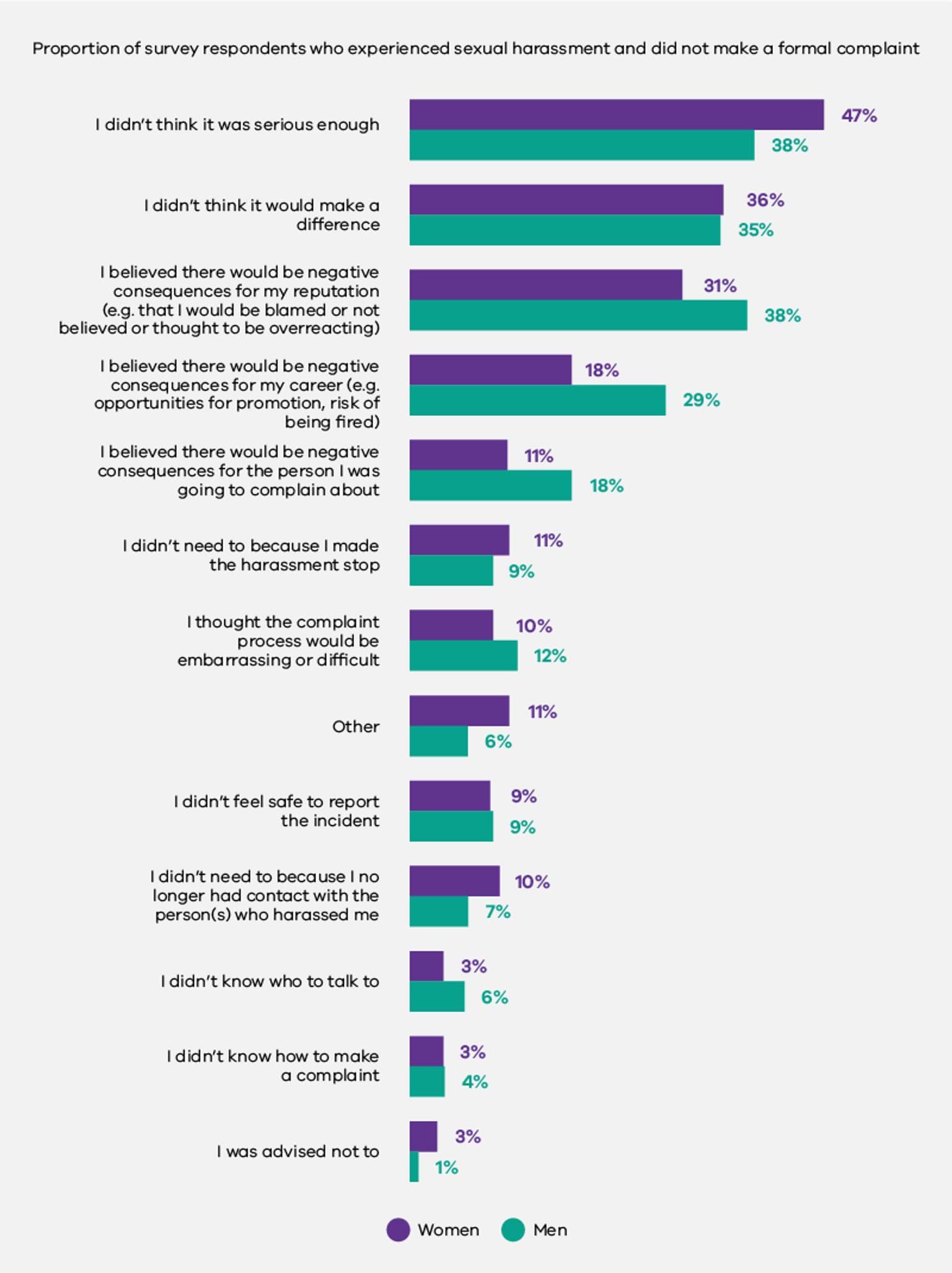

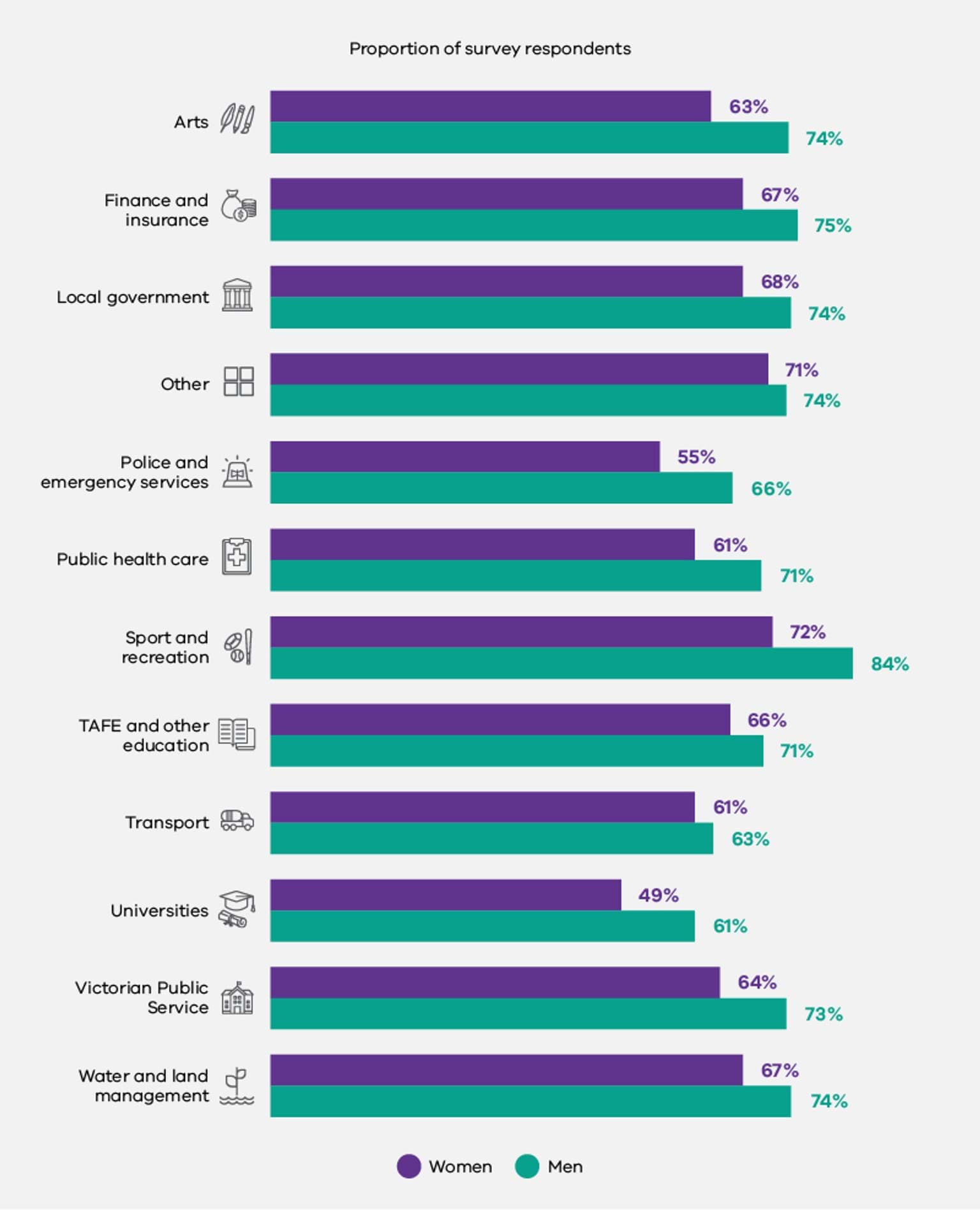

Across defined entities, women were 50% more likely to say they experienced sexual harassment than men. Sexual harassment occurred most frequently in majority-men and frontline sectors, such as Transport and Police and Emergency Services. Lack of formal reporting is a significant issue, with only 4% of women and 3% of men who had experienced sexual harassment lodging a formal complaint.

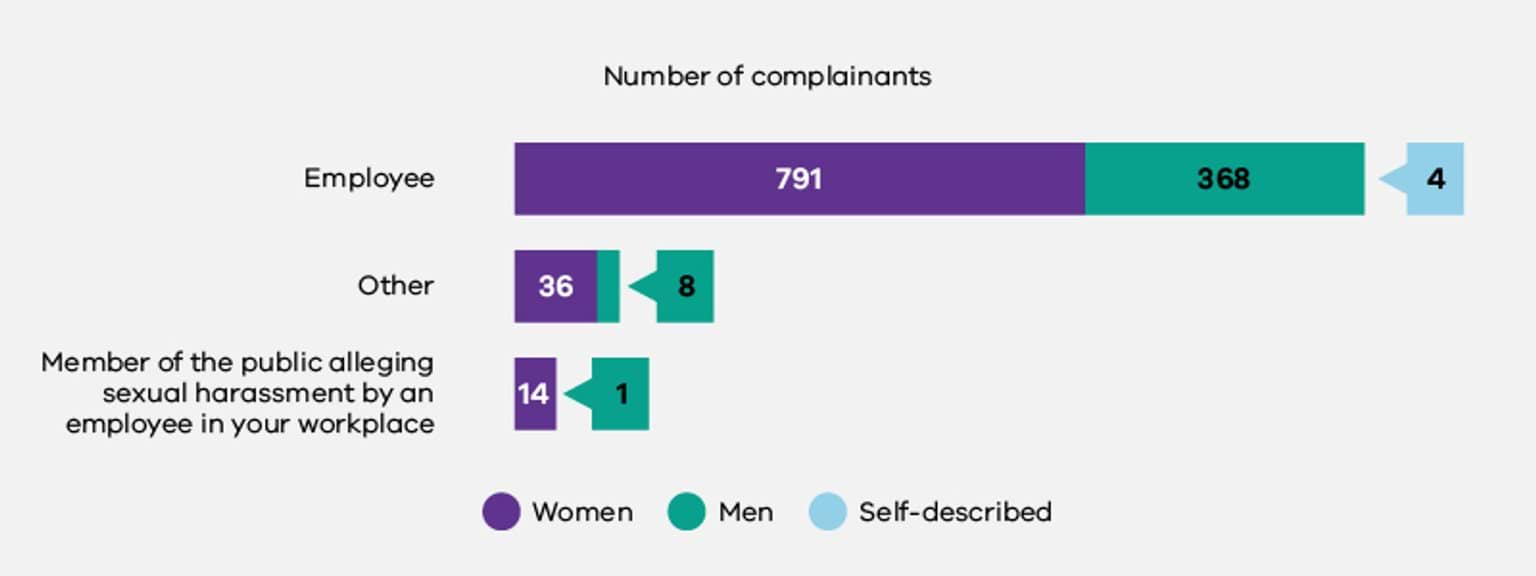

The Commission received data relating to formal sexual harassment complaints from less than two-thirds of organisations covered under the Act. Among those organisations that submitted information on formal reports of sexual harassment, there remained significant data gaps. These included a lack of data about the complainant’s relationship to the organisation, the outcomes of complaints, and complainants’ satisfaction with those outcomes. This is concerning, as comprehensive reporting and data collection systems are central to addressing workplace sexual harassment.

Flexible work and caring arrangements

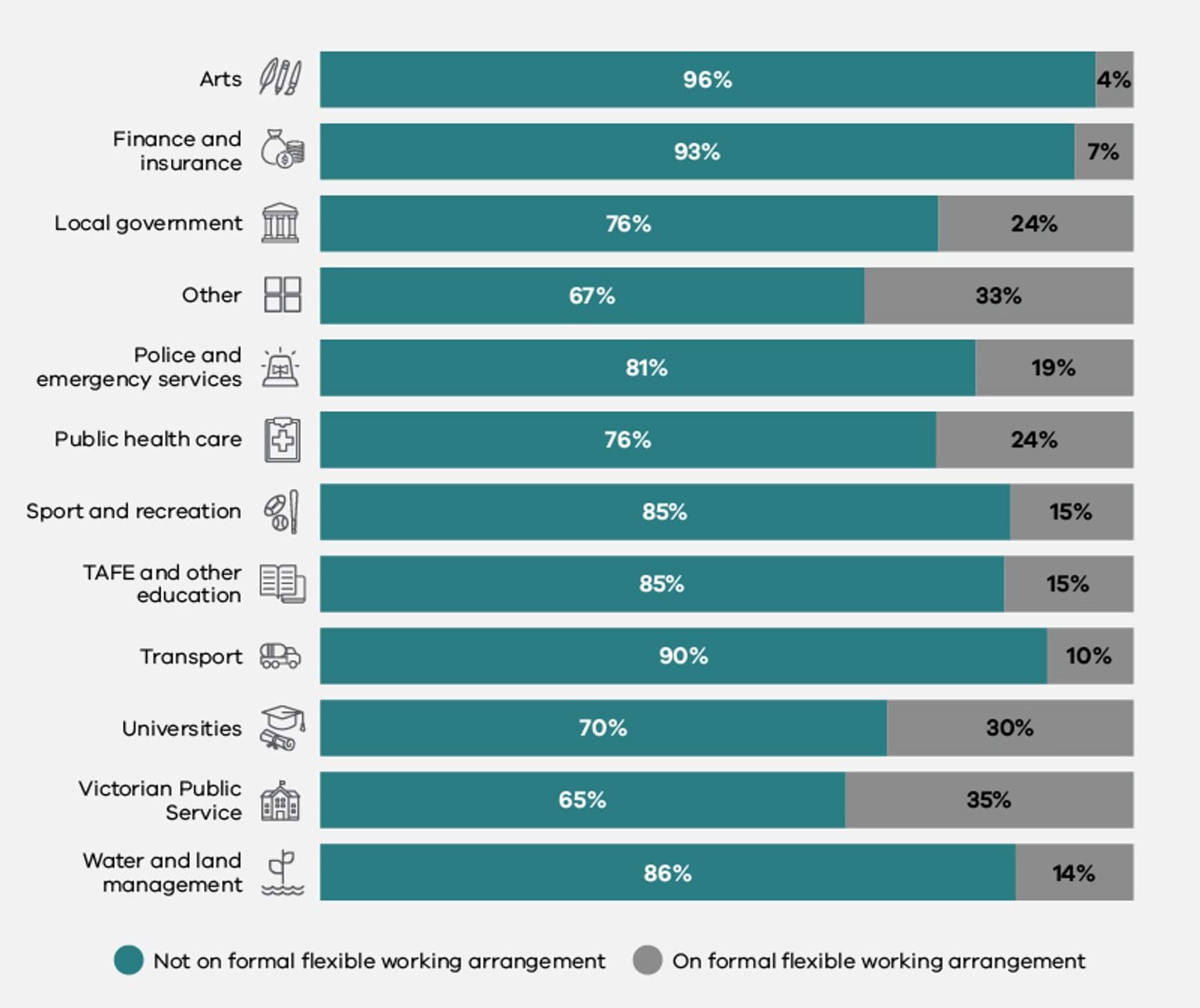

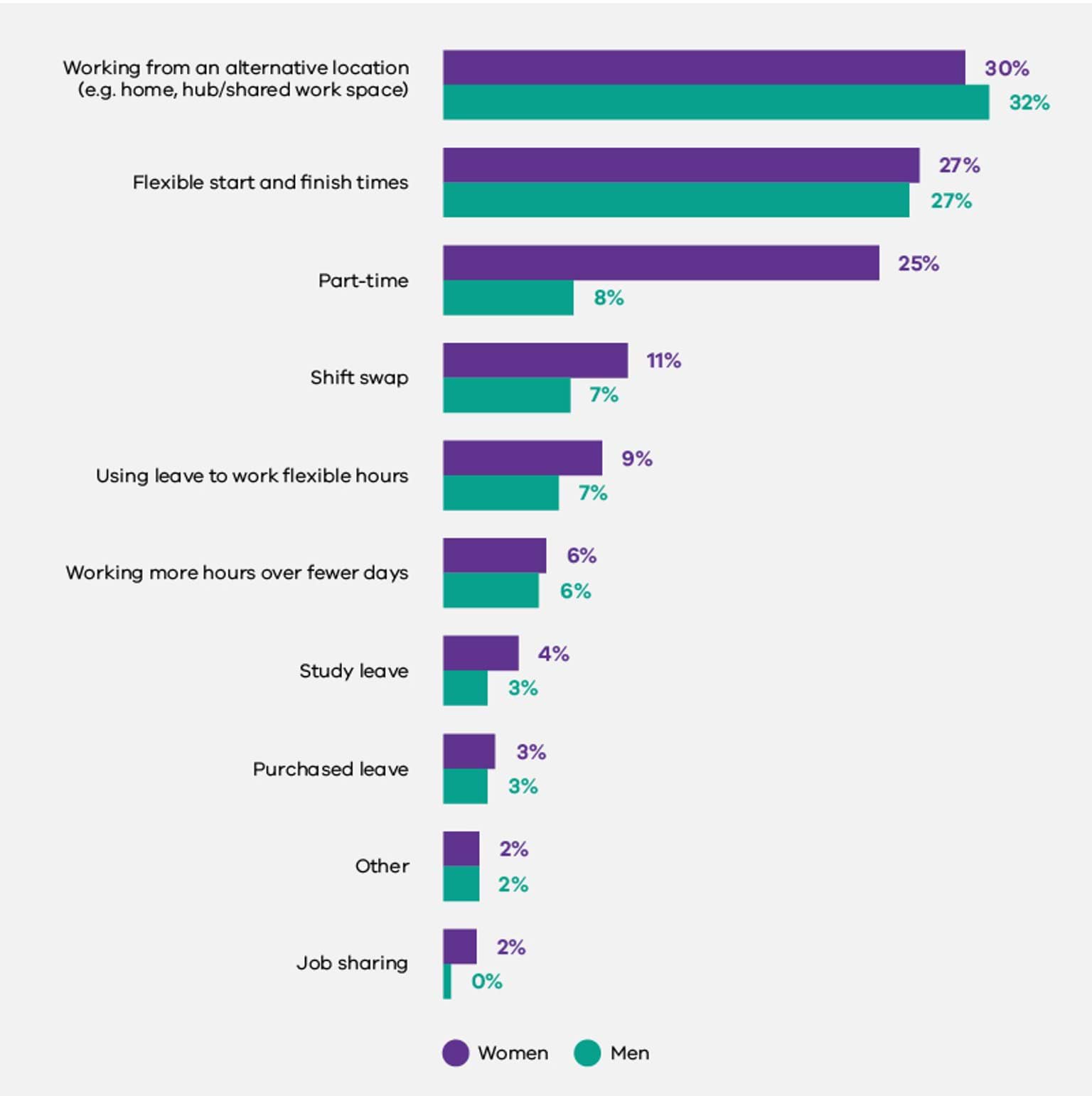

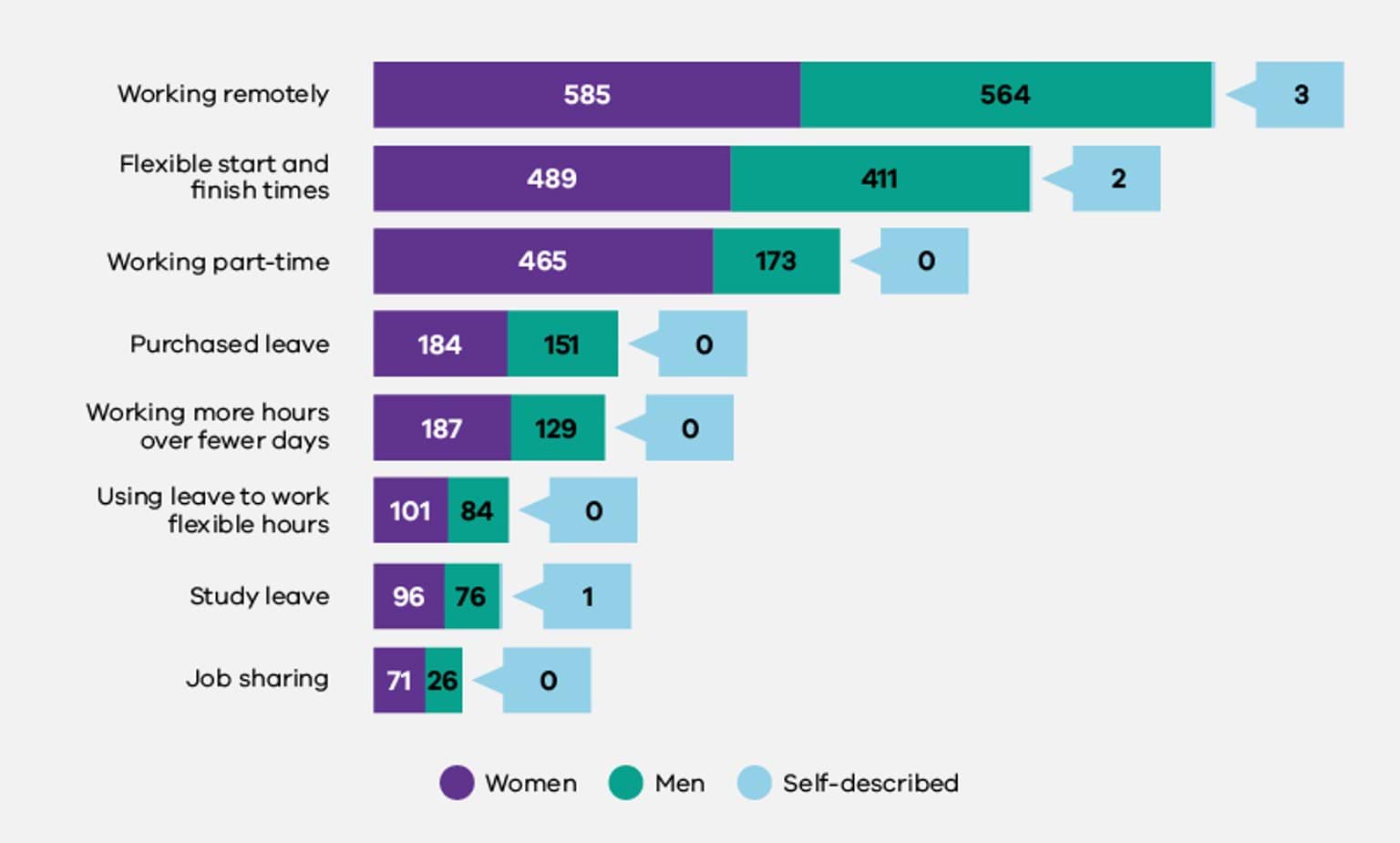

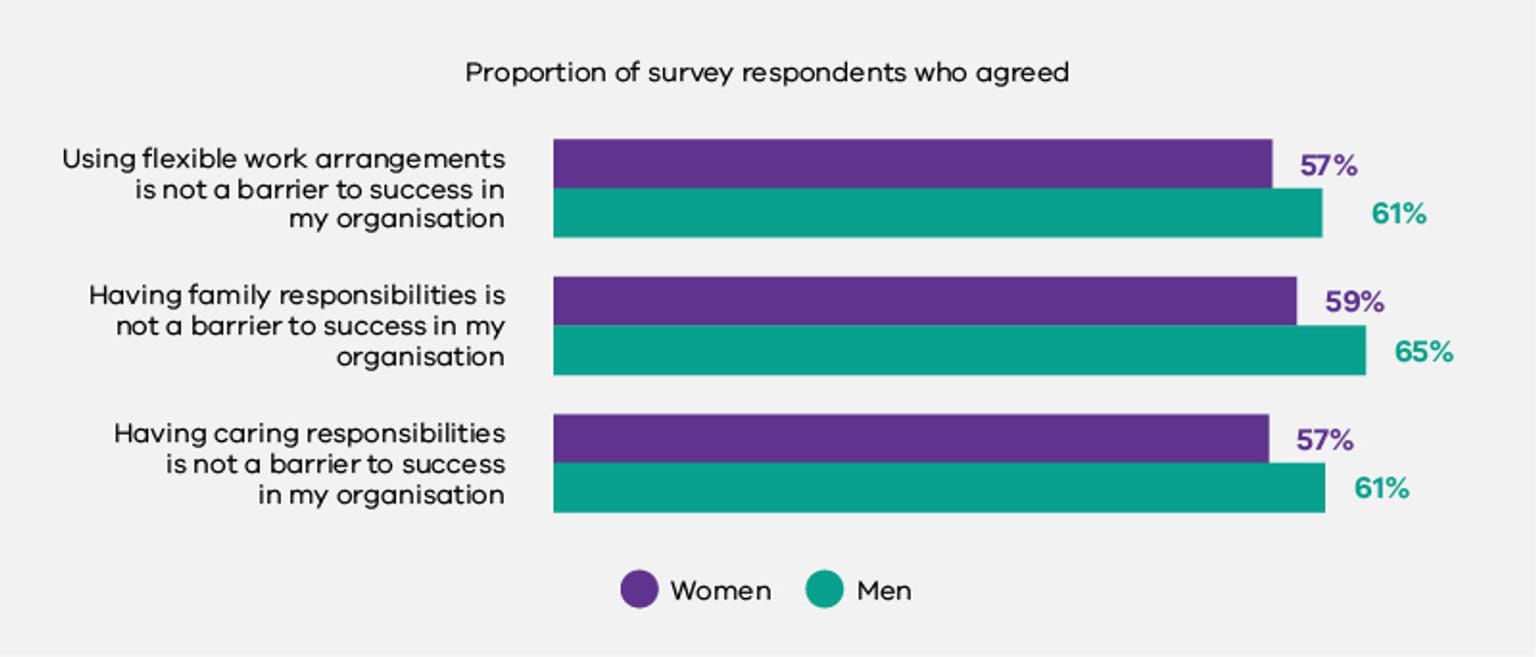

More than three-quarters of those individuals using formal flexible work arrangements were women. Women leaders were also more likely than men to take up part-time work and job-sharing opportunities – forms of flexibility that often entail a financial penalty.

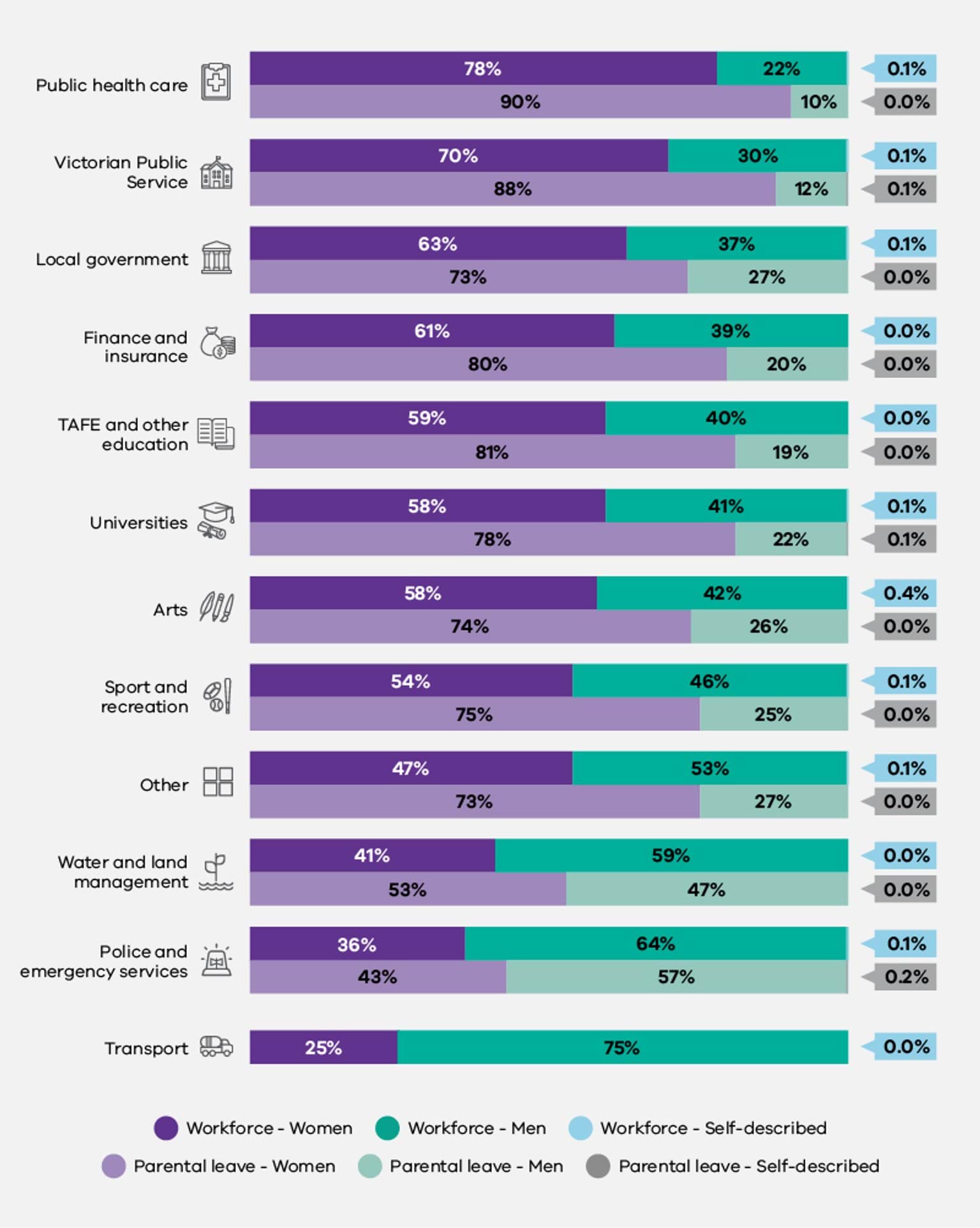

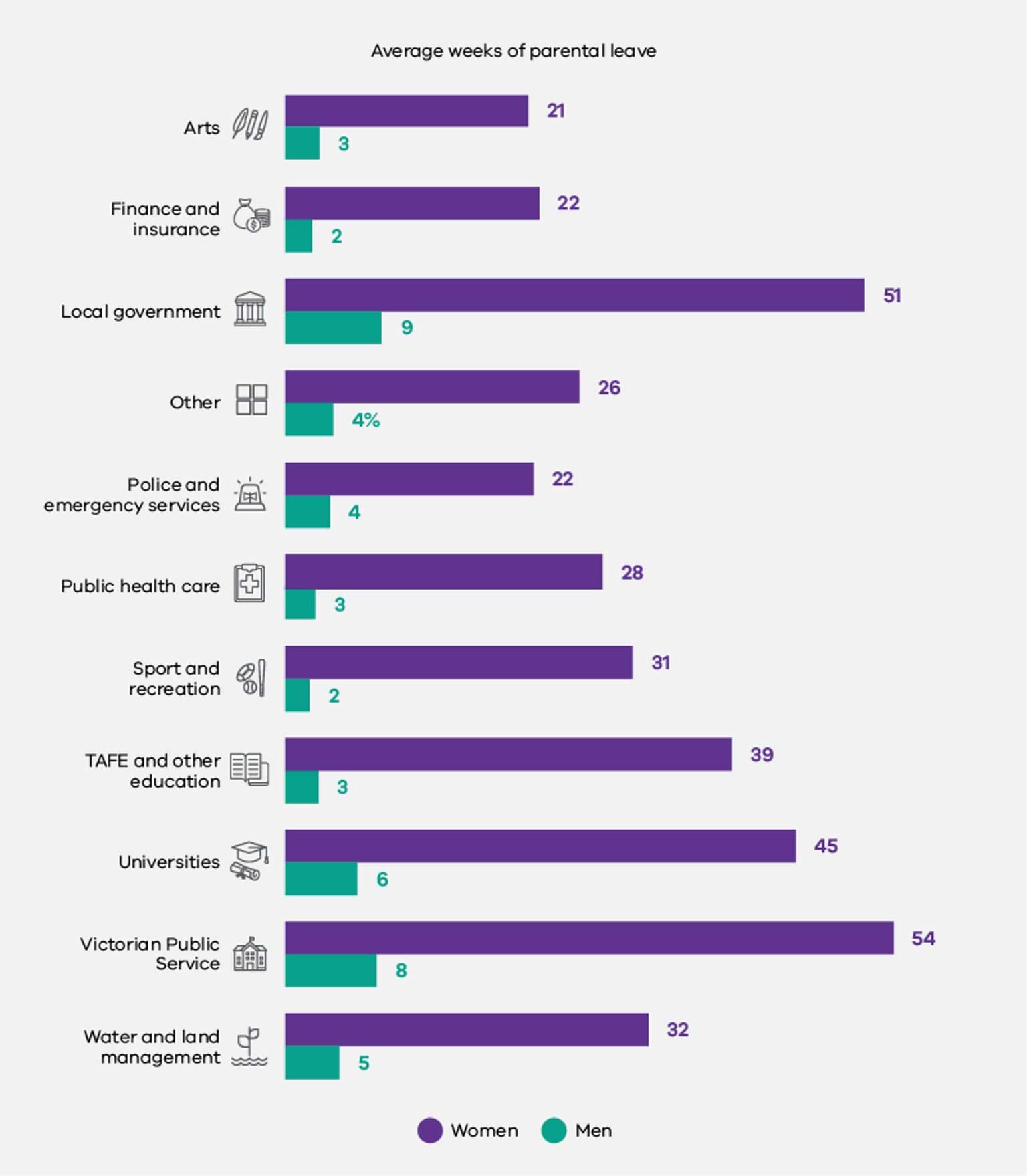

Nearly 8 out of 10 parental leave takers were women, and their leave lasted an average of 8 times longer than men’s.

Of those taking carer’s leave, 68% were women, and women were more likely to believe that flexibility, family responsibilities and caring are barriers to success in their organisation.

Taken together, these findings suggest that increasing men’s uptake of flexible working options and leave to care for children or others will have a significant positive impact on gender equality at work and in the home, and on women’s ability to participate equally in paid employment.

Summary of recommendations

|

Chapter |

Recommendation |

|

Chapter 1: Workforce gender composition and segregation |

Recommendation 1.1: Regular collection, analysis and reporting of accurate gender-disaggregated trend data on workforce composition is essential to improve workplace gender equality |

|

Recommendation 1.2: Build capability to effectively and safely collect intersectional workforce composition data |

|

|

Recommendation 1.3: Collect further data to help your organisation understand how forms of workplace discrimination might impact on workforce composition, occupational segregation and leadership opportunities |

|

|

Chapter 2: Equal pay |

Recommendation 2.1: Undertake organisation-wide, by-level and like-for-like pay gap analyses at least annually |

|

Recommendation 2.2: Assess all the factors identified as legitimate causes of pay variation for potential bias |

|

|

Recommendation 2.3: Invest in the development of workforce and system capability to create links between pay auditing and pay-related practices and decisions |

|

|

Recommendation 2.4: Invest in data collection systems that allow for more granular intersectional gender pay gaps to be measured and addressed |

|

|

Chapter 3: Workplace sexual harassment |

Recommendation 3.1: Collect and monitor both data that provides insight into the number of formal sexual harassment allegations and their characteristics, as well as anonymous survey data in relation to unreported experiences of sexual harassment |

|

Recommendation 3.2: Collect data on informal, as well as formal, workplace sexual harassment complaints |

|

|

Recommendation 3.3: Collect data about the experiences of people with intersectional attributes who report sexual harassment in the workplace |

|

|

Recommendation 3.4: Collect data on efforts to prevent sexual harassment in the workplace |

|

|

Chapter 4: Recruitment and promotion practices |

Recommendation 4.1: Embed gender equality data collection across recruitment, selection and onboarding processes |

|

Recommendation 4.2: Improve data collection about formal and informal career development and training opportunities, particularly for intersectional cohorts |

|

|

Chapter 5: Leave and flexible work |

Recommendation 5.1: Monitor both formal and informal flexible work arrangements, as well as feedback about how to improve uptake from employees, managers and executives |

References

- L Ryan et al., Laying the Foundation for Gender Equality in the Public Sector in Victoria: Final Project Report, University of Melbourne, 2022.

- M Cowper-Coles et al., Bridging the Gap? An analysis of gender pay gap reporting in six countries, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- For the first time under Australian gender equality reporting legislation, organisations covered by the Act were required to provide data disaggregated not only by gender, but across a range of attributes. As outlined in the Introduction, the Commission will publish insights from this intersectional data in a companion report on intersectionality, to be released in 2023.

Introduction

An introduction to the Gender Equality Act 2020 and this baseline report, including methodology and structure of the report.

The Gender Equality Act 2020

History of the Act

In 2016, Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence found that Victoria must address gender inequality in order to reduce family violence and all forms of violence against women. In response, Victoria’s first gender equality strategy, Safe and Strong, was released in December 2016, which committed to legislative change to promote gender equality.

In 2018, an exposure draft of the Gender Equality Bill was released for extensive community engagement and public consultation, including a Citizen’s Jury of Victorians. The feedback from consultation was overwhelmingly positive, with stakeholders recognising the Bill as a once-in-a-generation opportunity to influence gender equality policy, culture and attitudes across Victoria.

The Gender Equality Act 2020 (Act) passed the Victorian Parliament in February 2020 and came into force on 31 March 2021. The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector (Commission) was established to support the implementation of the Act.

Dr Niki Vincent commenced her appointment as Victoria’s inaugural Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner (Commissioner) in October 2020. Dr Vincent is supported in her role by the Commission. As Commissioner, Dr Vincent is responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Act and plays a key leadership role in promoting gender equality in Victorian workplaces and communities.

Scope of the Act

The Act is the first of its kind in Australia and is recognised globally as leading gender equality legislation. The Act applies to over 300 Victorian public sector organisations (known as defined entities) that have 50 or more employees, including universities and local councils (a total of approximately 450,000 workers or 12% of Victoria’s workforce). A list of defined entities and their industry groupings is provided at Annexure 1 of this report.

The Act requires defined entities to:

- develop, publish and implement a Gender Equality Action Plan (GEAP) every 4 years based on the results of a workplace gender audit

- make reasonable and material progress in relation to the Act’s workplace gender equality indicators, and publicly report on this progress every 2 years

- undertake gender impact assessments on all new policies, programs and services that impact the public and publicly report this activity every 2 years

- take into account that gender inequality may be compounded by other forms of disadvantage or discrimination, and have regard to this when developing strategies for improvement

The Act is unique and innovative in equality legislation. World-leading features include a positive duty on defined entities to consider and promote gender equality, the integration of consultation as a core feature of its procedural requirements, and a range of increasingly rigorous compliance and enforcement powers for the Commissioner.

The Act is the first formal integration of the concept of compounded discrimination (intersectionality) into Australian equality law. This means that defined entities must consider the disadvantage or discrimination that a person may experience on the basis of Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion and/or sexual orientation in addition to gender inequality across the majority of their obligations. This includes as part of their duty to conduct workplace gender audits, promote gender equality, develop their GEAPs, and undertake gender impact assessments.

The Act also includes powers for the Commissioner to conduct dispute resolution for systemic gender equality issues that adversely affect a group or class of employees within a defined entity, where an enterprise agreement or workplace determination has a relevant gender equality clause allowing for the Commissioner’s involvement.

Over time, the Act will:

- increase women's economic security – by addressing the gender pay gap and gendered segregation in the workforce, ensuring gender equitable recruitment and promotion practices to strengthen retention, and addressing structural inequalities preventing women from accessing leadership positions.

- increase workforce participation rates – by reducing discrimination experienced by carers and parents, increasing men’s access to and uptake of flexible work arrangements and non-traditional caring roles, and increasing flexible work arrangements for all.

- improve health and wellbeing outcomes – by reducing rates of sexual harassment in the workplace, increasing/providing access to and uptake of flexible working arrangements, appropriate return to work arrangements and family violence leave, reduced impact of poverty and stress through increased economic security.

In 2025, a review will be conducted of the first 4 years of the Act’s operation to understand if it is on track to achieving these long-term goals. This review is a requirement under the Act and will be tabled in the Victorian Parliament by the Minister for Women.

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector

The Commission supports the Commissioner to oversee implementation of the Act. It provides support to defined entities by helping to build their capacity to understand and meet their obligations under the Act and make meaningful progress towards gender equality in their organisations. The Commission is responsible for functions under the Act including data reporting and tracking of progress, research and evaluation, education and training, and dispute resolution.

The Commission sits within the Fairer Victoria division of the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing and comprised 16 FTE (including the Commissioner) on 30 June 2022.

First year of the Act’s implementation

The Commission was allocated $13.4 million over four years as part of the 2020/2021 Victorian State Budget to support implementation of the Act. Initial funding supported the provision of assistance to defined entities to meet their obligations and development of a reporting platform and public data interface.

Educating and supporting defined entities about the Act

The early stages of the Act’s implementation were largely focused on educating and supporting defined entities to understand the Act and meet their new obligations. This included:

- developing a range of comprehensive guidance materials, including for undertaking workplace gender audits and analysing audit data, developing GEAPs, conducting gender impact assessments, and dispute resolution

- sector-specific advice and leading practice resources, published on the Commission’s website

- conducting a series of educational roadshows for defined entities, heads of organisations, peak bodies and relevant unions, led by the Commissioner

- establishing an expert Panel of Providers to provide specialist and technical advice to the Commission and defined entities

- delivering tailored sector-wide workshops and training sessions for workplace gender audits, GEAPs and gender impact assessments.

In the 2021 calendar year, Dr Vincent undertook 254 stakeholder engagements, including speeches, panel events and meetings, and engaged in 25 media interviews and op ed articles.

Reporting platform

In 2021, the Commission developed the Act’s reporting platform, which defined entities use to submit and view their obligations including workplace gender audits, GEAPs and progress reports.

Through the reporting platform and data interface, the Commission has collected 67 million data points (up to 230,000 data points per organisation) – the most comprehensive gender-disaggregated dataset on public sector organisations in Australia. This data will help us understand how defined entities are individually tracking against the set of gender equality indicators contained in the Act as well as the broader state and nature of gender inequalities across the sector.

Submission extensions

The COVID-19 pandemic created many challenges for most organisations covered by the Act. With these exceptional circumstances and uncertainty about ongoing impacts, the Commissioner granted 2-stage extensions for organisations to submit their workplace gender audit data in late 2021 and their GEAPs in early 2022. At the time of writing, 100% of workplace gender audits and 99% of GEAPs had been submitted and most had been assessed as compliant under the Act.

Regulation and Act amendment

The Commission has also developed 2 stages of regulations to streamline processes to reduce the overall burden on defined entities, expand the dispute resolution function to enable universities and local councils to refer systemic gender equality issues to the Commissioner, and incorporate a set of gender pay equity principles, which defined entities must have regard to when developing their GEAP.

A third stage of regulations is currently in development. These regulations propose that defined entities undertake progress audits every 2 years as part of their progress reports, to allow the Commissioner to set the format in which audits must be submitted, to prescribe library corporations as defined entities under the Act, and to enable library corporations to access the dispute resolution function. The Commission will undertake a comprehensive regulatory impact statement and consultation process over 2022. It is intended that the regulations will come into effect in early 2023, ensuring sufficient time for defined entities to prepare for undertaking progress audits, which will be due for submission in October 2023.

Amendments to the Act were made in June 2022 through the Justice Legislation Amendment Act 2022 to improve information-sharing provisions relating to the Commissioner’s dispute resolution function. These changes improve accountability and transparency in relation to systemic gender equality issues and assist the Commissioner to educate public sector organisations and the wider community about gender inequalities.

A focus on intersectionality

To understand and address workplace gender inequality effectively, we need to understand and address how gender intersects with other forms of disadvantage and discrimination. We know that people who experience multiple, interacting forms of discrimination face higher levels of workplace inequality than those who only experience one form of discrimination, or none at all.4 We also know that there are major gaps in intersectional data collection.5

The Act contributes to addressing this data deficit by requiring defined entities to collect, analyse and submit gender-disaggregated and intersectional workforce data to the Commission.

In the first workplace gender audit cycle, the Commission requested a broad range of intersectional data. This request was ambitious, but the Commission knew that aiming high would encourage organisations to submit the most complete and highest quality data they could. It would also help organisations to plan for future reporting.

For many defined entities, it was the first time they had been asked to collect and report on data of this nature, and often their systems were not configured to provide what the Commission asked for. As a result, there are significant data gaps and other issues with the way this data has been provided, making it more complicated to collate and to analyse accurately and meaningfully.

To do this in a comprehensive way will involve a suite of research (see below) and analysis work that the Commission will undertake throughout the remainder of 2022 and into early 2023. The Commission will publish the results in a companion report to this Baseline report, focusing on intersectionality in the first half of 2023.

Research

Research into how to achieve gender equality in workplaces and the community is vital to driving strong progress in Victoria and beyond. Undertaking research related to the Act and its objectives is an important function of the Commissioner. Targeted research will maximise and expand the impact of the Act, and build the evidence base about what works in promoting gender equality for everyone. To support this important work, the Commission undertakes several activities including developing targeted research funding, engaging in knowledge-sharing and running a student research internship program.

In 2021, the Commission funded its inaugural research grants round. The funded research projects spanned from investigating the social and political circumstances that led to the establishment of the Act, international best practice in organisational gender equality, and how organisations can effectively remove barriers to equality for culturally and linguistically diverse women in the public sector.

The second annual research grants round, announced in August 2022, will have a strong focus on intersectionality, building the evidence base on how gender intersects with other experiences of disadvantage in Victoria’s public sector workplaces. Key areas of focus include the experiences of Aboriginal women, women with disability and women from non-English speaking backgrounds, gendered experiences in rural locations, and how pregnancy, parenting and/or caring can impact organisational gender equality. These projects will involve consultation with people with lived experience from different communities to ensure their experiences are represented accurately and respectfully.

As part of their final report, research teams will provide recommendations for defined entities to increase their capacity to sensitively collect and analyse more comprehensive intersectional data over time, as well as how to better address intersecting forms of inequality. The findings will also form part of the Commission’s companion report to this Baseline report, focusing on intersectionality, to be published in the first half of 2023.

This Baseline report

In a national first, this Baseline report provides an overview of the current state and nature of gender inequality across the span of organisations reporting under the Act. It will assist the Commission, defined entities, and the Victorian community to understand where the challenges and gaps are to progressing gender equality, and where efforts on improvement should be focused. It will provide a starting point from which to track change against each indicator, determine if reasonable and material progress is being made, and identify areas where the development of targets and/or quotas under the Act could drive greater progress.

While the Act creates a strong framework to assess and improve gender inequities in the public sector workforce, society-wide cultural change will require the majority of Victorian workplaces outside of the current scope of the Act to also make progress on gender equality. The work of the Commission and defined entities demonstrates leadership in workplace gender equality and provides an opportunity to inspire change beyond the public sector.

While not a ‘silver bullet’ for addressing gender inequality across our whole society, by measuring and understanding gender inequalities in workplaces, developing deliberate, evidence-based strategies and action to address these, and transparently monitoring and reporting progress, we can achieve more powerful progress towards gender equality in Victoria and beyond.

Gender-disaggregated data in this report

Due to the data challenges mentioned above, this first Baseline report focuses on the high-level findings of the inaugural workplace gender audit, disaggregated by gender.

For the purposes of the 2021 workplace gender audit, the Commission asked defined entities to collect gender-disaggregated data within three categories – women, men and self-described gender, recognising that some people identify their gender as being ‘woman’ or ‘man’ and some people understand their gender as a combination of these or neither. Some defined entities already collect gender data in this way, but many do not yet offer a self-described gender option.

Where there was sufficient data to report on the experiences of people of self-described gender in a meaningful way, the Commission has included this data in this report.

Intersectionality and this report

Alongside gender-disaggregated data, one area where the Commission has a more complete dataset is for experiences across different age brackets. This is because most organisations already have systems in place to collect and maintain accurate data about the age of their employees. Where possible, some of these age-related insights are included in this Baseline report.

In presenting this information, the Baseline report indicates where existing research and data tell us that intersecting forms of inequality have an impact on workplace gender equality. However, the Commission is not yet able to use its data to produce accompanying analyses for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, people with disability, people from diverse cultural backgrounds or religions, or LGBTQI+ individuals.

Intersectional data is sensitive. It is data about individuals who may belong to marginalised communities and who may experience discrimination and harassment.6 The Commission is dedicated to ensuring that its analysis of this data is robust and that it does not misrepresent the experiences of groups who already experience inequality.

Doing this work properly will take time, so in 2023 the Commission will produce a companion report to this Baseline report, focusing on the analysis of its intersectional data and incorporating key findings and recommendations from the research it has commissioned (and mentioned above).

Methodology

Background

This Baseline report is based on the 2021 workplace gender audit reports submitted to the Commissioner for Gender Equality in the Public Sector, Dr Niki Vincent by 298 organisations covered by the Act.

Under the Act, every defined entity was required to undertake a workplace gender audit in order to assess the state and nature of gender inequality in its workplace as at 30 June in the Gender Equality Action Plan reporting year. The first reporting year was 2021.

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector published workplace gender audit guidance in 2020 to advise defined entities of how to undertake a workplace gender audit.

The workplace gender audit required the collection of gender-disaggregated data – which is data that is broken down separately for women, men and gender diverse people – against the 7 workplace gender equality indicators set out in the Act. The indicators are:

- Gender composition of all levels of the workforce

- Gender composition of governing bodies

- Equal remuneration for work of equal or comparable value across all levels of the workforce, irrespective of gender

- Sexual harassment in the workplace

- Recruitment and promotion practices in the workplace

- Availability and utilisation of terms, conditions and practices relating to family violence leave, flexible working arrangements and working arrangements supporting workers with family or caring responsibilities

- Gendered segregation within the workplace

If available, defined entities were also required to report data about Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion and sexual orientation and were required to have regard to the disadvantage or discrimination that a person may experience on the basis of these attributes in addition to gender inequality (i.e. compounded or intersectional gender inequality).

Data measures and types

The 2021 measures were selected based on an extensive evidence review of local and international literature, consultation with key stakeholders including the Commission’s practice leaders group composed of 10 organisations representing different industries covered under the Act, the Commission’s Implementation Support Advisory Committee made up of leaders from across key stakeholder organisations including relevant unions and peak bodies, as well as commissioned expert research advice from the Social Research Centre.

As part of the 2021 workplace gender audit, organisations covered by the Act collected two categories of data – workforce data and employee experience data. The workforce data was extracted from defined entities’ internal data collection systems and provided to the Commission through an Excel template that was uploaded through the Commission’s reporting platform. The employee experience data was collected through surveys. The Victorian Public Sector Commission administered the questions required by the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector via the People Matter Survey to about 90% of organisations covered by the Act. The remaining defined entities used another survey provider or administered the survey in-house and then uploaded the results to the Commission’s reporting platform. Each organisation covered by the Act was surveyed separately, and the results were reported as percentages of respondents. Items with fewer than 10 responses were suppressed by the survey provider to protect respondents’ privacy.

Information provided to the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector was managed in line with relevant privacy laws. Defined entities were responsible for their own compliance with relevant privacy laws, including the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 (Vic) (PDP Act).

Evaluating workplace gender audit compliance

The Commission conducted a series of automated and manual tests measuring the quality, consistency and completeness of each workplace gender audit submission. The main objective of these tests was to determine whether each organisation met its obligations under the Act. For example, the Act requires that audits have regard to the equal remuneration workplace gender equality indicator – so if an organisation did not include pay data in its audit, it was evaluated as non-compliant. About 90% of organisations submitted compliant audits on the first attempt.

The secondary objective was to determine how closely each submission aligned to the guidance and data specifications we published. For example, the workplace gender audit guidance instructed organisations to report their employees’ pay as annualised figures. If an organisation instead reported its employees’ hourly pay rates, it was evaluated as compliant but not meeting our specifications. In cases like this, the Commission notified the organisation that their audit submission had been accepted, but that some of their data would be excluded from analysis and reporting.

Every organisation received feedback on their audit submission and was given an opportunity to revise their data. More than 90 organisations revised their audit data, including more than 50 voluntary resubmissions where organisations elected to improve the quality of their submission.

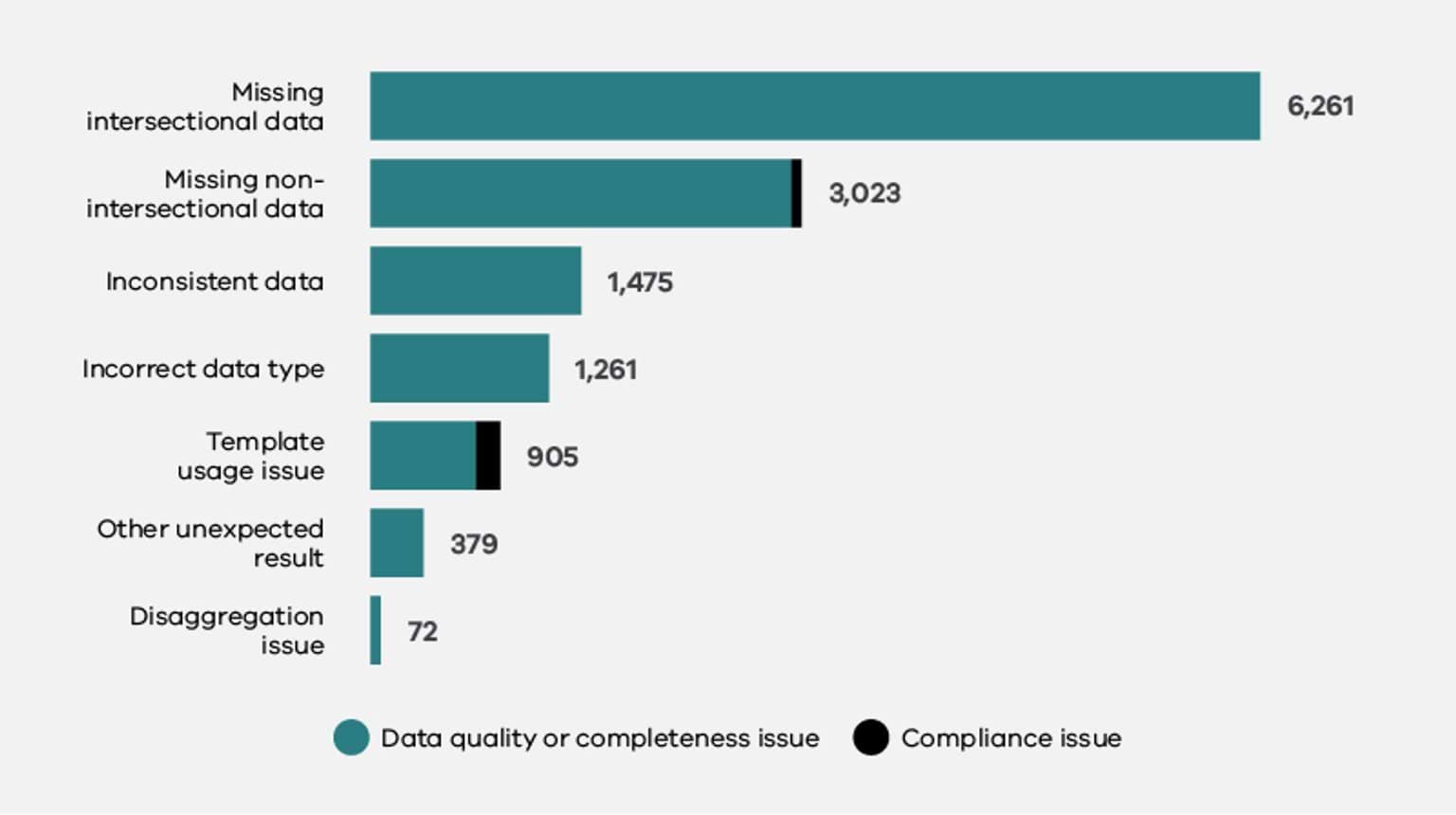

Workplace gender audit data quality

The most common issue observed with audit submissions was missing data. This audit was the most comprehensive workforce data collection exercise many organisations had ever undertaken, so some gaps in datasets were anticipated by the Commission.

The Commission also learnt that most organisations do not yet collect the demographic data required for intersectional analysis. This means organisations are missing out on the opportunity to identify areas where gender inequality may be compounded by other forms of disadvantage or discrimination.

Within the data organisations supplied, the most common issue observed was inconsistency between different parts of an audit. For example, if one data table indicated that an organisation employed 20 women on a part-time basis, but another table included only 19 women employed on a part-time basis, both tables were flagged for the organisation’s attention.

Baseline analysis datasets

To calculate baseline results at the sector and industry levels, the Commission compiled audit submissions into 3 analysis datasets. Each was comprised of audit submissions received by the Commission as at 30 June 2022.7

Fig 0.2. Summary of workforce gender audit analysis datasets

|

Dataset |

Description |

Used for: |

|

Aggregated workforce data (296 organisations) |

Pre-aggregated data drawn from organisations’ payroll and HR systems, presented mainly as headcounts |

|

|

Aggregated employee experience data (293 organisations) |

Pre-aggregated data drawn from employee experience survey results, presented as percentages of respondents |

|

|

Unit level workforce data (273 organisations) |

De-identified employee-level data drawn from organisations’ payroll and HR systems |

|

Because the employee experience results were reported as percentages of respondents within each organisation, the survey results have been weighted based on the size and gender composition of each defined entity to produce the estimates included in this report.

The Commission received assistance in data analysis assistance from EY and GenderWorks in the preparation of this report.

Structure of the report

This report is structured in accordance with the key workplace gender equality indicators set out in the Act. Each chapter begins by explaining the importance of measuring progress against that indicator, followed by an overview of what data was collected for each indicator. This is followed by an examination of key findings, at industry and whole-of-sector levels. Each chapter concludes with a short discussion and includes recommendations relating to improving data collection and analysis processes to drive workplace gender equality progress.

References

- P Nangia and T Arora, ‘Discrimination in the workplace in Canada: An intersectional approach’, Canadian Journal of Sociology, 2021, 46(2):147–177.

- M Glennie et al., Gender pay gap reporting in Australia -Time for an upgrade, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership, 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- K Crenshaw, ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics’, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, 1(8): 139–167.

- Note that organisations may supersede prior audit submissions to correct errors or omissions. This may result in discrepancies between the results presented in this report and those presented through the Commission’s insights portal.

Workforce gender composition and segregation

This chapter looks at data for the indicators ‘gender composition of all levels of the workforce’, ‘gender composition of governing bodies’ and ‘gendered segregation within the workplace’.

Introduction

Women’s participation in the paid Victorian workforce has increased substantially over the past five decades, rising from 43.8% in February 1978 to 62.3% in June 2022.8 In contrast, men’s participation has fallen slightly from 80% to 72.1%.9 More recently, the Victorian Public Sector Commission has begun to measure the labour force participation of gender diverse Victorians, with an estimated 0.7% of Victorian public sector employees identifying as trans, non-binary or gender diverse, and 0.3% identifying as intersex in 2021.10

Despite these important shifts, the Victorian labour market remains highly segregated by gender, a persistent but repairable feature of labour markets around the world.11 This is because women’s increased workforce participation has not been consistent across industries and occupations.12

Unequal gender representation occurs vertically within organisations, with women often being overrepresented in lower-level occupations, classifications and pay grades. It also occurs horizontally across industries, as women constitute the majority of workers in lower-paid industries, such as community care and social assistance. This causes women to be disproportionately featured in the lower quartile of the earnings spectrum across the Victorian workforce.

Key issues: Why was this measured?

Women are underrepresented in management roles

Women are often concentrated in lower-paid administrative roles and have slower rates of career progression due to a number of cultural and structural factors, such as stereotypes about the types of work different genders may be interested in or can perform, unconscious and conscious biases in hiring, promotion and performance development, expectations around overtime, travel or time spent in the physical office, as well as attitudes towards flexible work.13

Women are overrepresented in lower-paid areas

Traditionally ‘masculinised’ sectors and industries (both those that are disproportionately majority-men industries, but also those industries and roles that are traditionally regarded as ‘men’s work’) tend to be better remunerated and respected within society. Conversely, traditionally feminised sectors and industries (which are majority-women industries and associated with feminine stereotypes related to caring) are less respected and lower paid.14

Collectively, women employed in the Health Care and Social Assistance industry and the Education and Training industry represent over one-third of all employed women in Victoria.15 These industries have lower salaries than majority-men industries,16 pay the lowest proportion of superannuation and discretionary payments,17 and have higher than average part-time and casual role rates.

Data on intersectional inequality is sparse

Research has shown that migrant and refugee women are more likely to be engaged in low-income, low-skill and insecure work,18 facing intersecting barriers to employment and promotion, such as lower English proficiency, insufficient work rights, lack of recognition of international qualifications and social exclusion.19

Similarly, we know that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are less likely to hold executive and management positions compared to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men,20 and that women with disability are often given marginal jobs far below their capacity and are more concentrated in precarious and informal employment.21

Those who fall outside of the gender binary – including those who are non-binary, trans, gender diverse, agender, genderfluid or use any other term, as well as individuals who may identify as women or men but who do not conform to societal norms ascribed to these groups – may experience complex forms of discrimination or disadvantage (such as microaggressions and transphobia) in sectors seen as ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ because they do not conform to these narrow gender stereotypes.22

Insufficient data collection and research has been undertaken on the specific experiences of these groups in workplace settings across different industries.

How was this indicator measured?

Workforce composition

Defined entities were asked to provide data in relation to the composition of their workforce (by classification level to CEO), disaggregated by gender, employment basis and (where possible) intersectional data.23

As the gender composition of a workforce changes substantially depending on who is working full-time, part-time and casually, the Commission has measured this indicator:

- based on total headcount rather than FTE, meaning full-time, part-time, and casual workers were all counted the same way, and

- within each of the organisation’s full-time, part-time and casual workforces separately, relative to the organisation’s total workforce.

Given we know that unequal workforce composition is driven by a range of organisational, cultural and structural factors, such as leadership views on flexible working arrangements, the Commission also considered employee experience responses in relation to discrimination and flexible working arrangements.

Governing body composition

Defined entities were asked to provide data in relation to the composition of their governing body (such as a board of directors, or elected councillors in the case of local government) disaggregated by employment basis, gender, and intersectionality attributes.

Gender segregation

This indicator was measured by considering the gender composition of employees by occupation according to the ANZSCO classification codes, as assigned by defined entities, both across industries (for example, by calculating the gender composition of workers employed in a ‘Manager’ classification across organisations within a particular sector) and within defined entities (for example, by calculating the gender composition of workers employed in ‘Clerical and Administrative’ classifications within a particular defined entity).

Further detail about how each aspect of the measures was defined can be found in the glossary at the end of this report.

What was found: Key data insights

Total workforce and industry composition

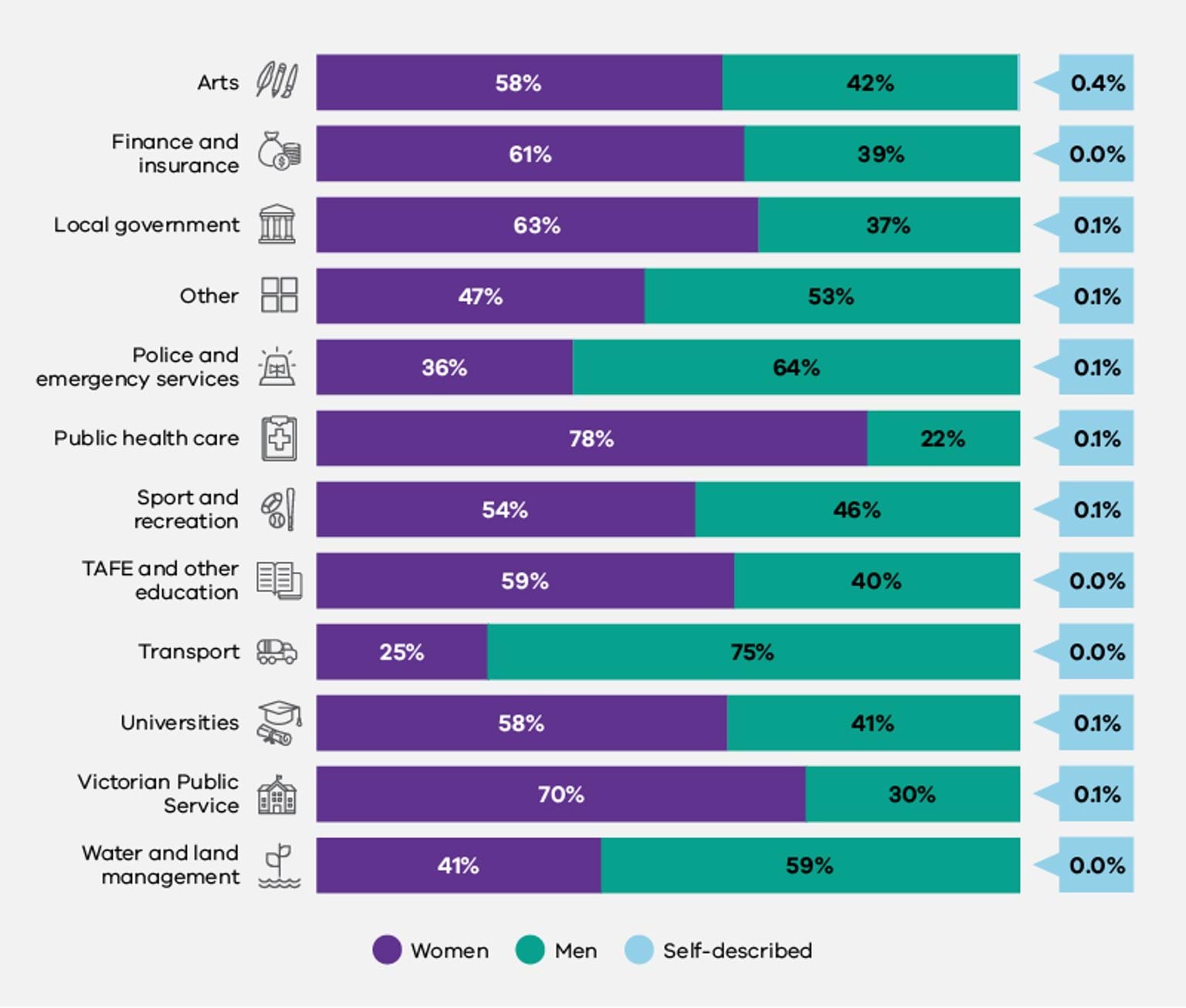

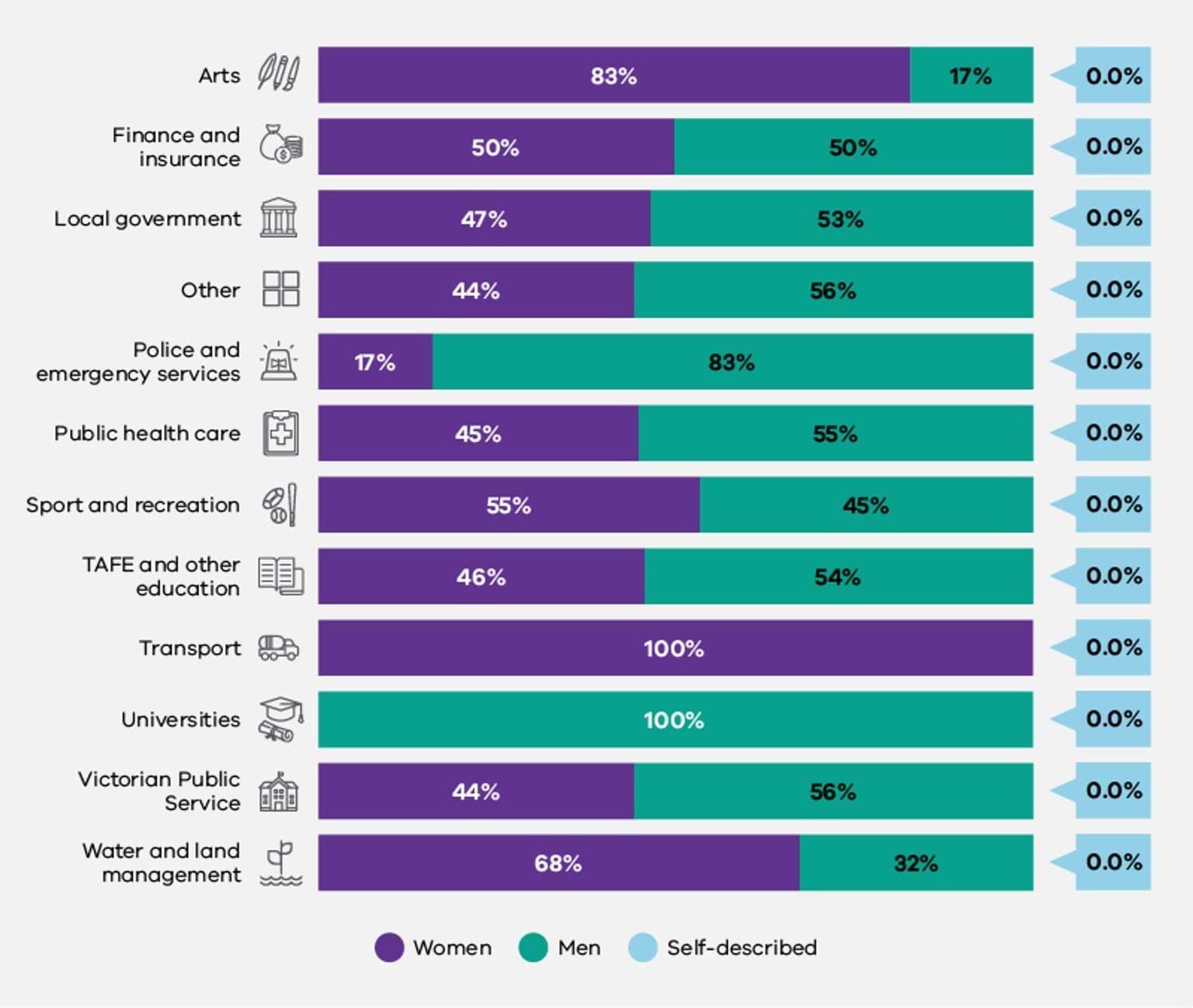

The total workforce of defined entities comprised 66% women, 34% men, and at least 0.1% people of self-described gender.24

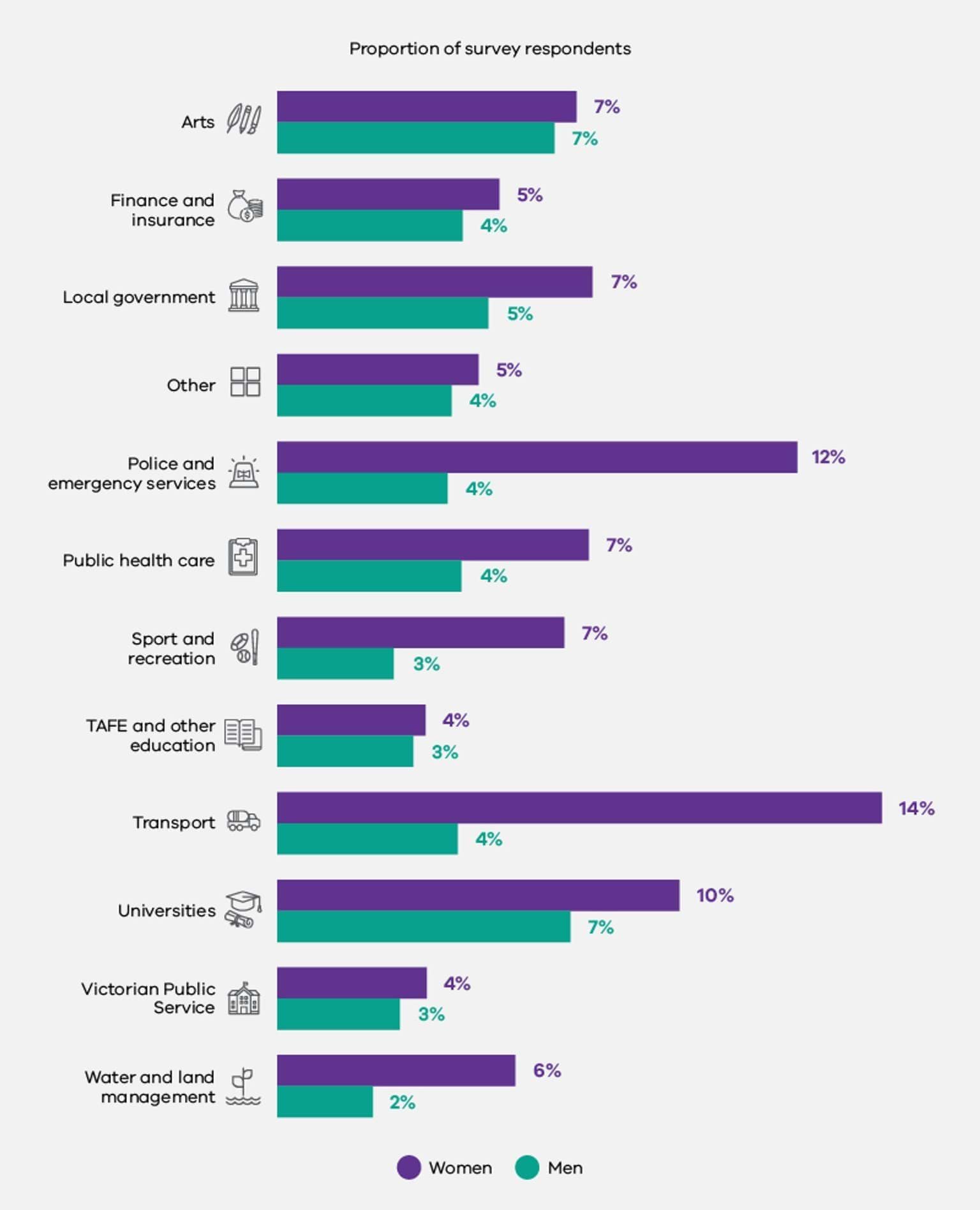

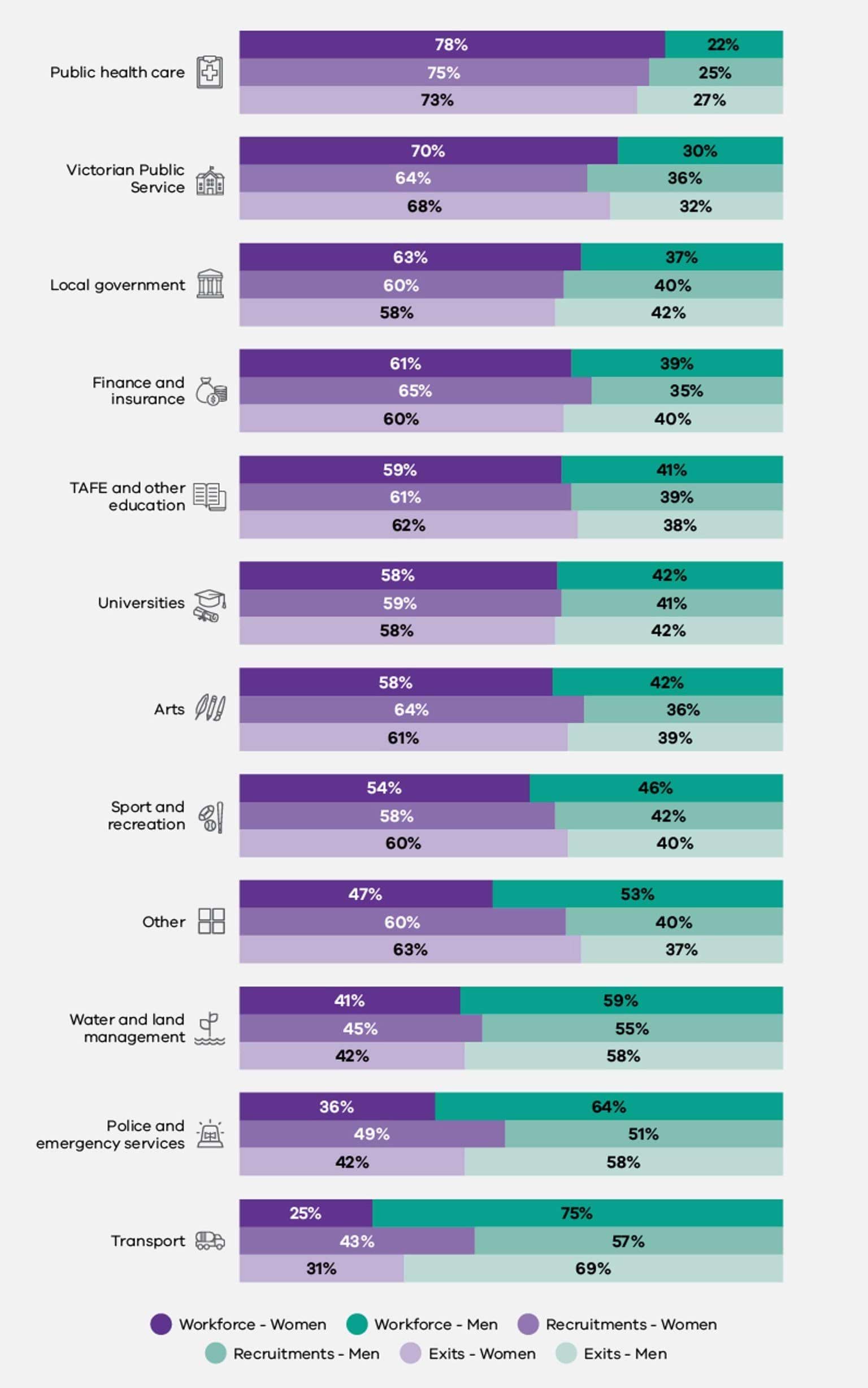

As can be seen in Figure 1.1, women outnumbered men in 8 of the 12 industry groups, including the Arts, Universities, TAFE and Other Education, Local Government and Finance and Insurance industry groups. The Public Health Care industry group had the highest proportion of women (78%), followed by the Victorian Public Service (70%). In contrast, the Transport industry group had the highest proportion of men (75%), followed by Police and Emergency Services (64%). Note that there are slight differences in how the Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector and the Victorian Public Sector Commission define industries within the public sector. As the workplace gender audit required defined entities to submit their data at an organisational level, different types of workforces within a single organisation are included within the same industry grouping. For example, in this Baseline report, all schools and school staff (including cleaners, teachers, administrative clerks and others) are classified as belonging to the Victorian Public Service industry, as they are employed by the Department of Education and Training. However, the VPSC splits these workforces into different industry groups as relevant.

These findings are consistent with others across the world25 where women are estimated to make up 70% of the global health sector workforce26 and over 75% of workers in the health and social care sector in most OECD countries27 but represent only 18.6% of the transport sector across the European Union,28 18% in Sweden,29 and 23% in Canada.30

Gender composition by employment type

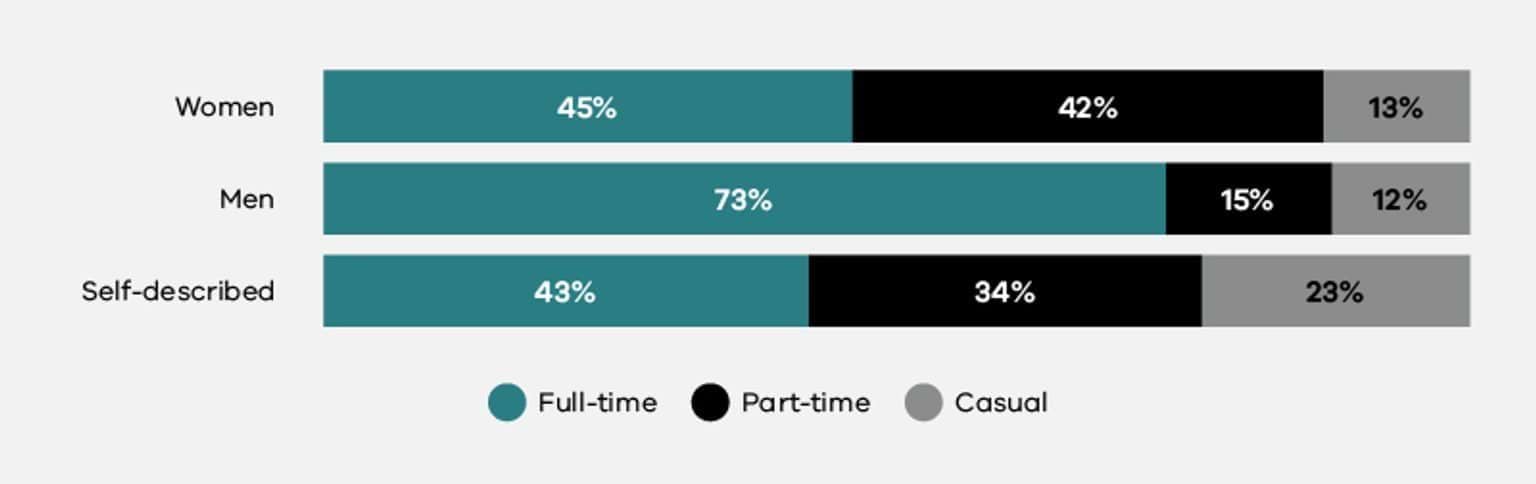

Women and individuals of self-described gender were more than twice as likely to work in part-time roles than men – with only 15% of men working in part-time roles, compared to 42% of women and 34% of individuals of self-described gender.

In comparison, 45% of women worked in full-time roles, compared to 73% of men and 43% of people of self-described gender. The imbalance in the proportion of women and men working in full-time roles is similar to that in the private sector in Australia (where 41% of women work on a full-time basis, compared to 67% of men).31 However, the imbalance is significantly greater than in the New South Wales public sector (where 58.1% of women work on a full-time basis, compared to 41.9% of men),32 and in countries such as Canada (where 75.6% of women and 81.8% of men were in full-time roles in 2021)33 and the UK (where 62% of women and 87% of men were working full time as at May 2022).34

As can be seen in Figure 1.2, while the gender composition of casual employment in defined entities was relatively balanced between women and men (13% and 12% respectively), people of self-described gender were almost twice as likely (23%) to be in casual employment (see boxed section for further information).

Gender composition in leadership roles

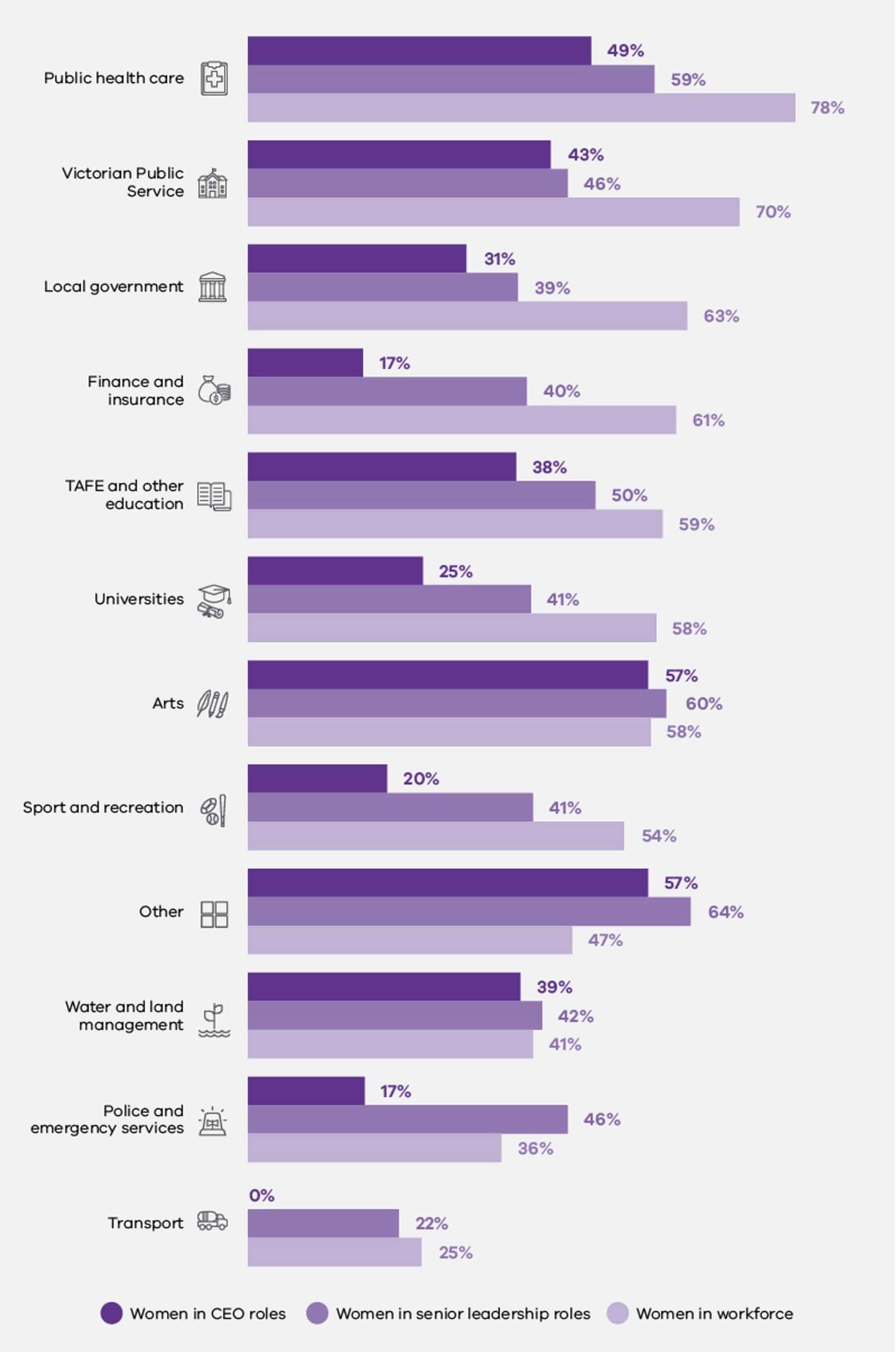

Women were underrepresented in senior leadership positions across defined entities reporting under the Act, with women comprising 66% of the workforce, but only 46% of senior leadership roles.

In 8 of the 12 industry groups identified in Figure 1.3, women were less represented in senior leadership roles than in the underlying workforce.

Across the industry groups, the largest differences in proportions were found in the Victorian Public Service, where women made up 70% of the workforce but only 46% of senior leadership positions, and the Local Government industry group, where women made up 63% of the workforce and only 39% of senior leadership positions (amounting to a 24% difference in each industry group). This is followed by the Finance and Insurance industry group where women made up 61% of the workforce but held only 40% of senior leadership positions and 17% of CEO positions.

This underrepresentation is consistent with imbalances found in the NSW public sector, where women make up over 65% of the public sector workforce, but only 40% of senior executive level roles.37 However, it is more pronounced than in the public service in the UK, where women make up 54.2% of the civil service and 46.7% of the senior civil service.38 Similarly, in New Zealand, women made up 61.8% of the public service workforce as of 30 June 2021 but only 53.5% of the top 3 tiers of senior management.39

Organisations covered by the Act fared only marginally better than the private sector. According to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency, in 2021 women made up over 50% of private sector employees, however they comprised only 32.5% of key management positions and only 19.4% of CEOs.40

This situation is also reflected internationally. For example, a survey of 69 organisations (470,000 employees) in Canada found that while, on average, 45% of all entry-level employees were women, only 39% of Managers, 25% of C-suite employees and 15% of CEOs were women.41

Across defined entities, 61% of CEO-level roles were filled by men, despite men comprising only 34% of the workforce. In contrast, while women comprised 66% of the workforce, they held only 38% of CEO-level roles. As noted above, this is just under double the percentage of female CEOs in the Australian private sector, which is 19.4%.42

When we consider how this operates across particular industry groups in the Commission’s data, men were disproportionately represented in CEO roles in 10 of the 12 (83%) industry groups. Women were most likely to hold CEO positions within the Arts, Other, Public Health Care and Victorian Public Service industry groups, and least likely to hold CEO positions within the Transport, Finance and Insurance, Police and Emergency Services and Sport and Recreation industry groups.

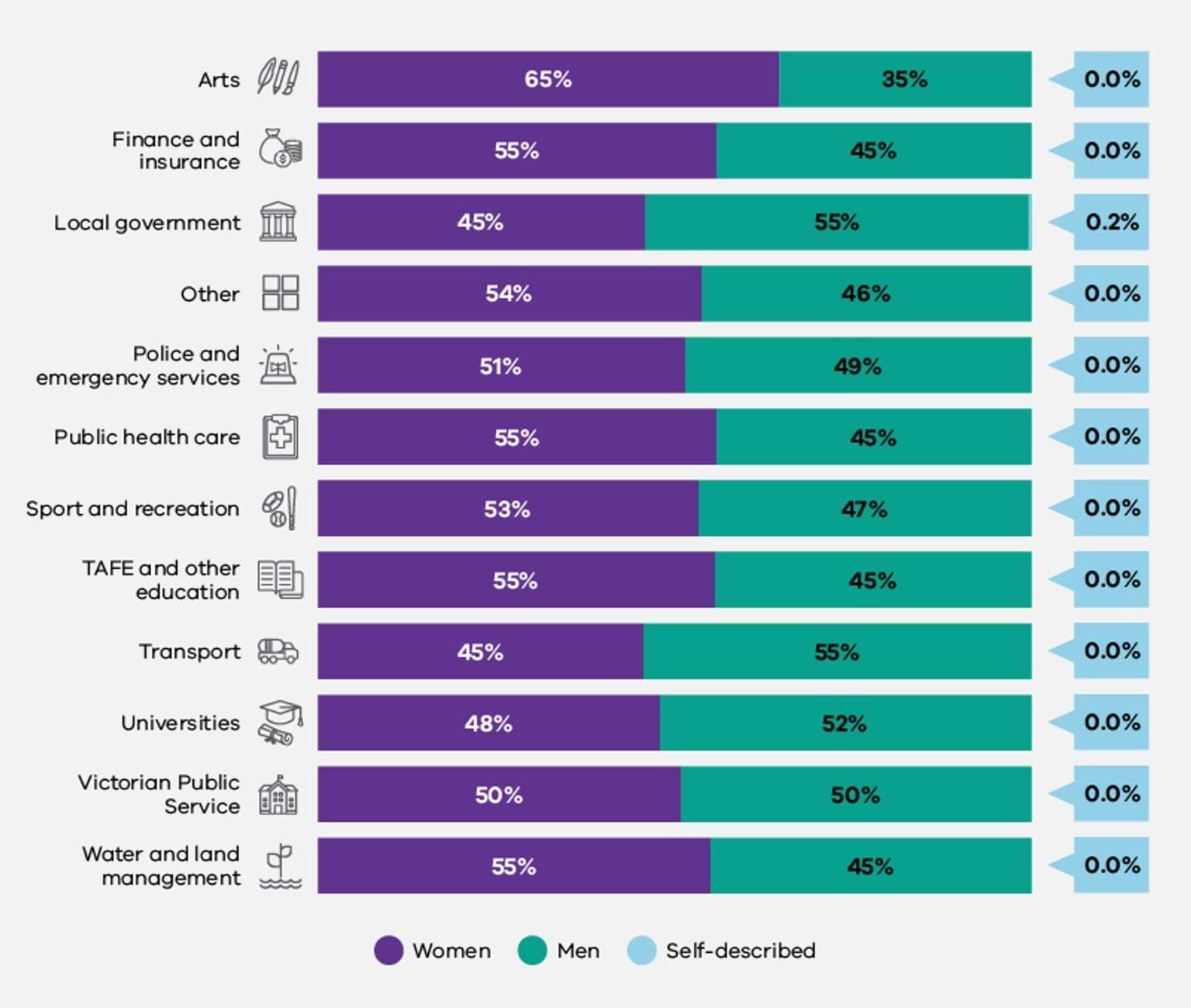

Gender composition of governing bodies

Boards, councils, committees of management and other governing bodies have a powerful role in strategic, financial and risk oversight and decision-making. Equal governing body representation is therefore critical to ensure decisions made at this level reflect the diversity of the workforce and the community more broadly.

The gender composition of governing bodies across defined entities overall was largely balanced between women and men (with 1,226 women and 1,128 men serving on governing bodies). Only one person of self-described gender was reported to serve on a public sector governing body.

National and international reports suggest that defined entity boards therefore have better representation of women than federal Australian Government boards (where, as of 30 June 2021, women held 49.6% of positions across all Australian Government board appointments and 39.1% of chair and deputy chair positions).43 Similarly, the board of organisations covered under the Act also fared better than the boards of private sector organisations across Australia more broadly (where women hold only 29.9% of board seats and 11.7% of board chair positions) as well as in Canada (where the average percentage of women on boards is 30% and in chair positions is 9%) and the European Union (where 30.7% of board seats are held by women and only 10% of board chairs are women).44

Victorian Government targets in place since 2015 requiring 50% of new government board appointments to be women have clearly been successful in generating greater gender balance in public boards in Victoria.45

While there was a reasonable balance between the total number of women (128) and men (140) serving as governing body chairs across the data as a whole, this balance was not maintained at the industry group level (Figure 1.5). All University governing body chair positions were occupied by men, while all Transport industry governing body chair positions were held by women. The data also shows a significant gender imbalance in the Arts industry group, in which women occupied 83% of chair positions, and in the Police and Emergency Services industry group, in which they held only 17% of chair positions.

Occupational gender imbalances

The 2021 workplace gender audit data shows the occupational gender imbalances present in defined entities compared to those in the broader Australian workforce. Defined entities were closer to gender balance than the broader Australian workforce in 4 of 6 occupation groups, and further away from gender balance in 2 of the occupation groups.

Across both 2021 workplace gender audit data and national data, women held almost three-quarters of Clerical and Administrative roles and over half of Professional roles. Men held the majority of Technician and Trade positions in both datasets (62% within defined entities and 84% within the Australian workforce). These findings are also reflected internationally. For example, in Canada women are most concentrated in occupations in health (79.6%), education, law, and social, community and government services (68.9%), whereas men occupy 93% of trades and transport and equipment operation occupations and 73.5% of occupations in manufacturing and utilities.46 Similarly, men in the UK have the highest employment share in skilled trade occupations (92%), while women are most concentrated in ‘caring, leisure and other service’ occupations (75.6%), and administrative and secretarial occupations (67.7%).47

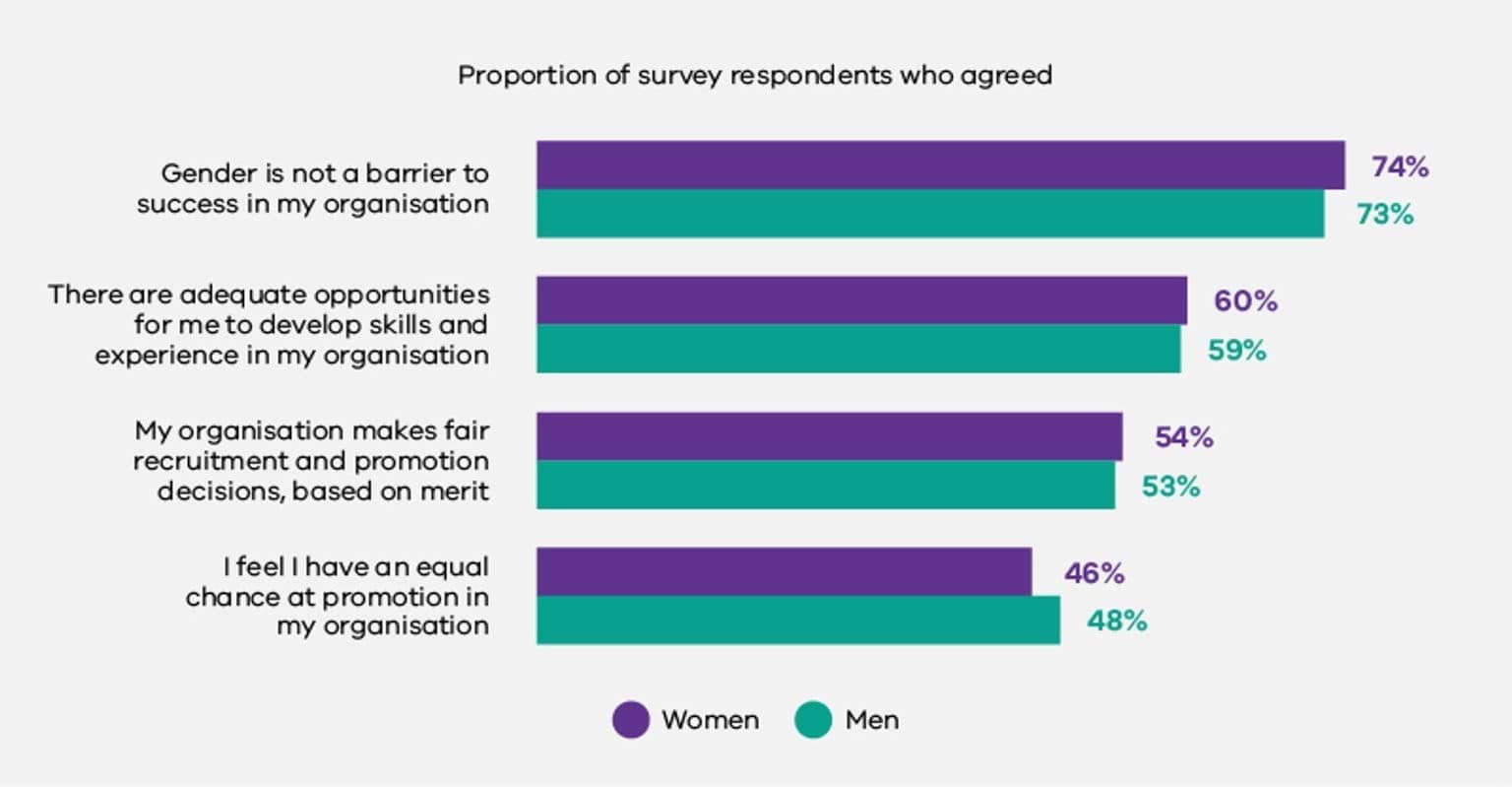

Reports of workplace discrimination

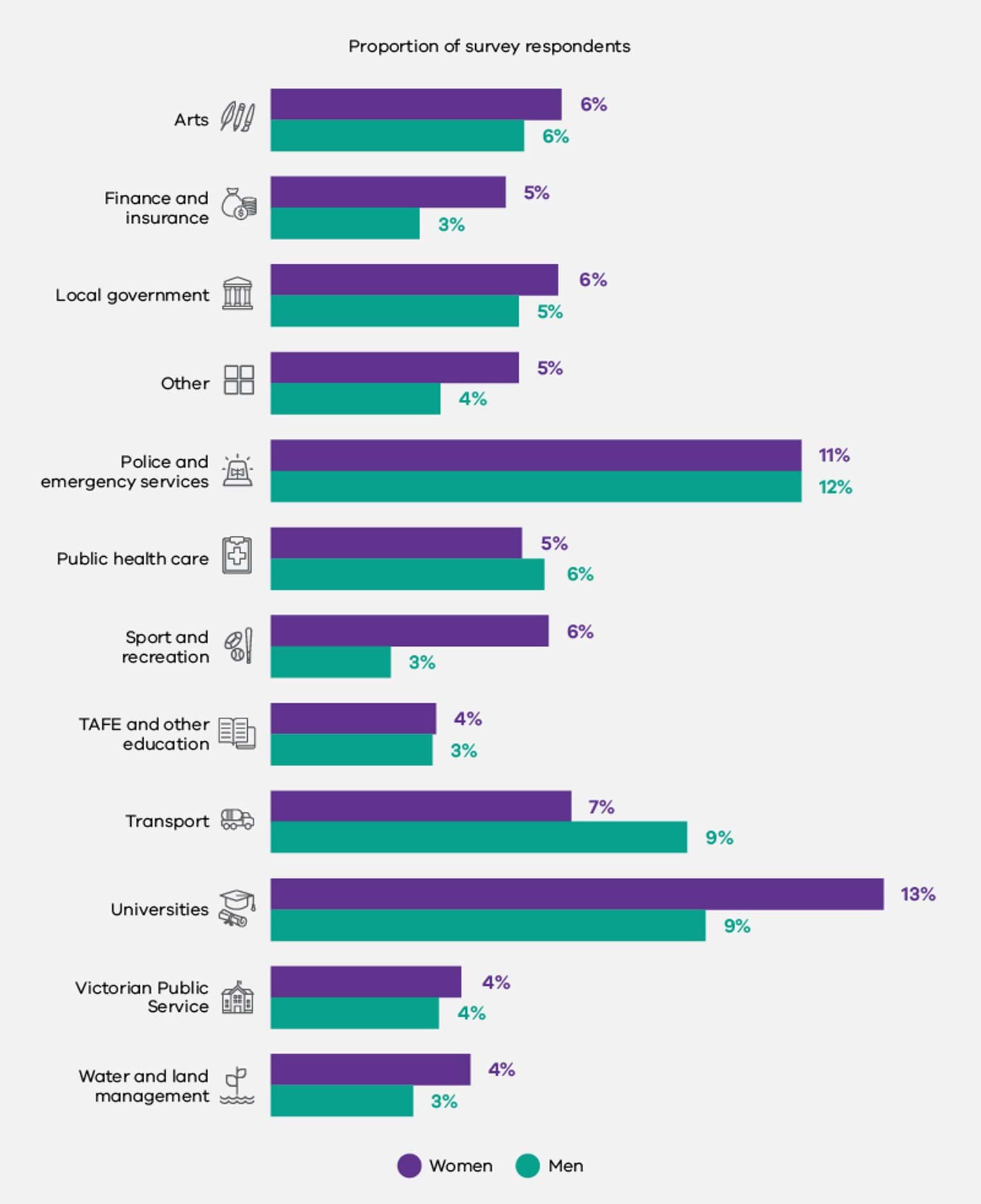

Among survey respondents, women and men reported experiencing workplace discrimination48 at similar rates (Figure 1.7, below). About 6% of men and women said they had experienced discrimination at work in the previous 12 months.

Reports of discrimination were most common for women working in the University industry group (13%) and for men working in the Police and Emergency Services industry group (12%).

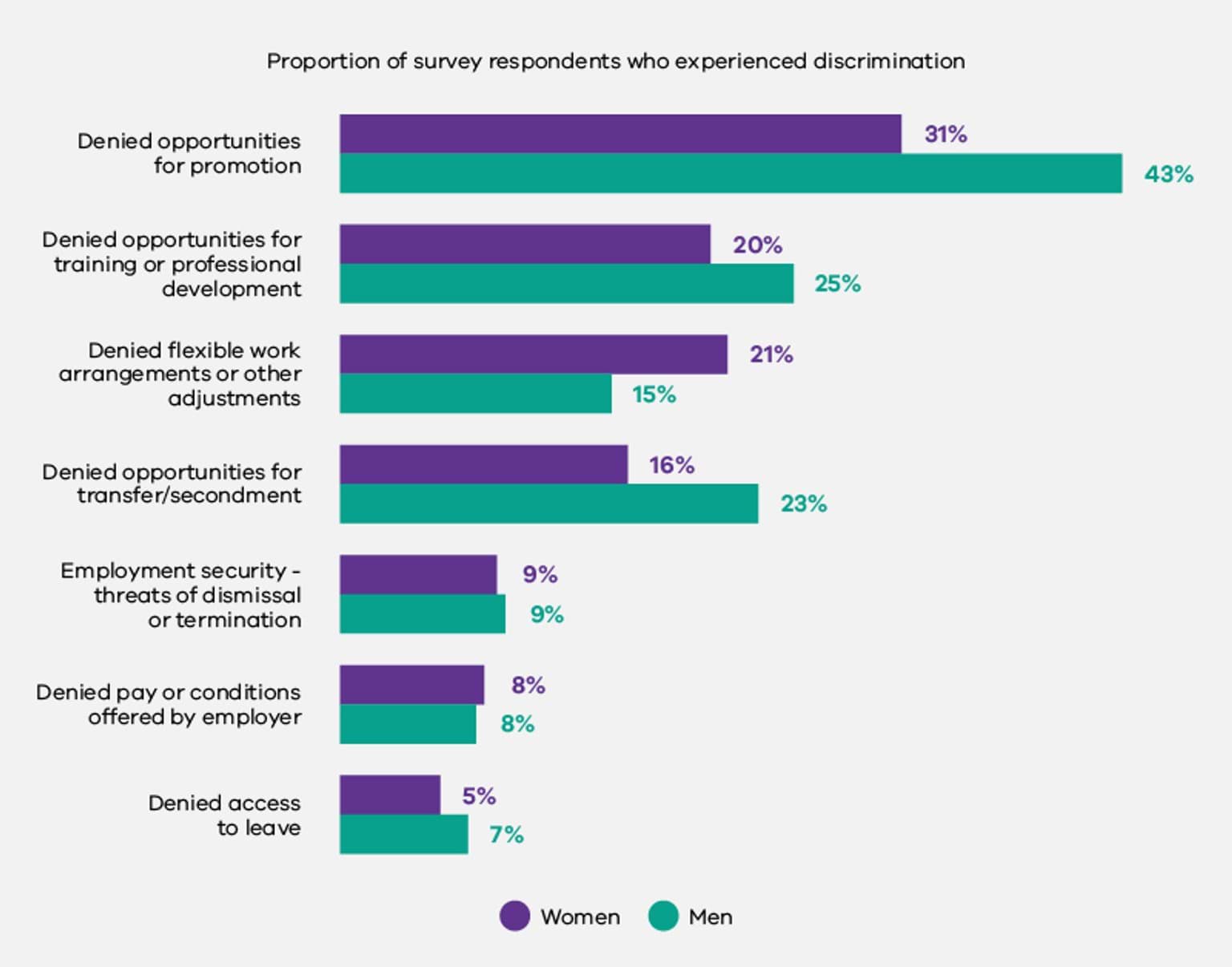

As can be seen in Figure 1.8 below, for both women and men, the most common type of discrimination reported was being denied opportunities for promotion.49 This was reported by nearly half of those men who said they had experienced discrimination compared to less than one-third of women.

The only form of reported discrimination that was more common for women than for men was being denied flexible work arrangements or other adjustments. This affected 21% of women who said they had experienced discrimination and 15% of men.

Discussion

Increasing the representation of women and gender diverse people in traditionally majority-men industries and occupations – including leadership roles, as well as increasing the representation of men in traditionally majority-women occupations and industries, can lead to a range of positive outcomes. This may include a decrease in organisational and industry-specific pay gaps, improved organisational performance and workplace productivity, as well as increased safety.50

The Commission’s data revealed an imbalance in the proportion of women and men working in full-time roles (with 42% of women working part time, compared to 15% of men). This imbalance is greater than in countries such as Canada and the UK.

It is important to acknowledge the possible connection between the availability and accessibility of flexible working arrangements (or lack thereof) in Australian workplaces and the higher proportion of women working on a part-time basis.51 It has been hypothesised that an overrepresentation of women in part-time work may ‘reflect the fact that a lack of flexibility often drives women out of the full-time workforce, either into part-time or casual roles, or away from the workforce altogether’.52 This explanation is reinforced by the significant amount of support offered to workers in Canada and the UK to work flexibly, and the comparatively high proportion of women working on a full-time basis in these countries. It is also supported by a study of leading practice organisations in gender equality strategy, policy, and implementation in Australia.53

While the Commission’s data identified several industry groups with strong women’s workforce representation, these industries did not demonstrate a proportionate number of women in management positions. For example, women comprised 61% of the workforce in the Finance and Insurance industry group, yet only 40% of senior management positions and 17% of CEO positions. Similar findings in the private sector have been linked to a ‘Glass Elevator’ effect experienced by some men in majority-women industries – which propels them into leadership positions at a quicker pace than their colleagues who are women.54

Interestingly, the data shows that while women comprised only 36% of the Police and Emergency Services industry group, they held 46% of senior leadership positions. Similarly, while women comprised only 25% of the Transport industry group, they held 22% of senior leadership positions. Given women’s overall underrepresentation in these industry groups, this may suggest that some majority-men industry groups are successfully engaging in deliberate strategies to increase women in leadership (although this has not yet flowed through to CEO positions in these industries).

Research has found that having women in CEO positions can create a ‘trickle-down effect’ (whereby increasing the number of women at the top of an organisation increases women’s representation in the level immediately below).55 Certainly, in this dataset, the industry groups with the highest proportion of women CEOs also have the highest proportion of women in senior leadership positions. For example, the Arts and ‘Other’ industry groupings have the highest proportion of women CEOs (with 57% of CEO positions held by women) and the two highest proportions of women in senior leadership positions (60% and 64% respectively). Trend analyses within the Commission’s dataset over coming years will allow investigation into whether this ‘trickle-down’ effect of increasing women in leadership can be identified.

Data from the first workplace gender audit under the Act shows that defined entities achieved greater gender balance on their governing bodies than both private boards and government-appointed boards Australia-wide. This success can, at least in part, be attributed to Victorian Government targets for government board appointments. In place since 2015, these targets require 50% of new government board appointments to be women.56 The success of this gender target framework in Victoria reflects existing research demonstrating that targets and quotas for women in leadership are effective in accelerating women’s representation at the top of organisations.57

Forms of workplace discrimination can contribute to gender inequality in workforce composition, occupational distribution, and organisational leadership.58 For example, denial of career development opportunities as a result of discrimination on the basis of gender or other attributes can contribute to a lack of diverse leaders in an organisation.

Discrimination may be a contributing factor to imbalances in workforce gender distribution across different levels among defined entities. Notably, industry groups with majority-women workforces do not demonstrate commensurate numbers of women in leadership roles. Discriminatory views or practices within organisations may be implicated in this failure to translate strong women’s representation into strong women’s leadership.

Forms of discrimination can be both direct and indirect, and may relate to gendered expectations, such as rewarding presenteeism and overwork.59 However, it must be noted that a lack of women’s leadership in these industries is likely due to a constellation of factors, including issues related to career development practices, caring responsibilities, leave and flexible work, which are covered in subsequent chapters of this report.

Reports of discrimination within employee survey data can also be shaped by resistance to gender equality, or perceptions of ‘reverse discrimination’. It is notable that the majority of men who reported experiencing discrimination in the survey data from defined entities indicated that they had been denied opportunities for promotion. This may reflect existing data and research on resistance to proactive strategies to increase the representation of women, particularly in majority-men organisations and industries, where men interpret these strategies as a form of gender-based discrimination against them.

The recent review undertaken by the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC) into sex discrimination and sexual harassment in Victoria Police showed evidence of this. VEOHRC’s report noted the existence of ‘widespread perceptions among some male employees and a small number of female employees of “reverse discrimination”’, while finding no evidence of actual systemic discrimination against men.60 That survey respondents who were men identified promotion as a key arena where they experienced discrimination could potentially reflect resistance to moves towards greater gender equality in promotion practices.

Recommendations

Regular collection, analysis and reporting of accurate trend data on workforce composition across all levels of an organisational hierarchy (including on boards and decision-making committees), in all occupations and across employment types (full time, part time and casual), and across all business units, divisions and geographical locations, is essential to addressing inequalities in workforce composition and gendered segregation in organisations. Collecting analysing and reporting this data will allow defined entities to understand whether strategies to improve gender equality included in their Gender Equality Action Plans (GEAPs) are working, and if not, where attention may need to be focussed.

The Act requires that defined entities have regard to the disadvantage or discrimination that a person may experience on the basis of Aboriginality, age, disability, ethnicity, gender identity, race, religion and sexual orientation, in addition to gender inequality. In order to do this, organisations need to break down or ’disaggregate’ their workforce data in an intersectional way.

In collecting, analysing and reporting on this data, organisations need to be sensitive to employee safety and privacy considerations and allow employees the discretion to self-identify.61

If an organisation does not currently have access to intersectional data, it is important to plan for how to collect this in future, including how to ensure employees with different attributes feel safe to disclose personal information. Engaging with your workforce – and ensuring diverse participation in this engagement – can help build a culture of safety.62

A review of existing data gaps will help your organisation to plan next steps. You can access further advice on the Commission’s website.63 Further information and recommendations will also be provided in the companion baseline report on intersectional data when this is published in the first trimester of 2023.

Inequalities in the composition of your workforce, the distribution of occupations, or the composition of your organisational leaders can be influenced by various forms of workplace discrimination. This can include bullying and other negative behaviours, the denial of career development opportunities, a lack of support for flexibility or a denial of professional development due to part-time work, a lack of support for carers and parents, or a lack of employment stability. Where people with certain attributes are more likely to experience workplace discrimination, this can contribute to skewed distributions across levels, occupations, or leadership groups in your organisation.

It is therefore important to collect and analyse data regarding workplace discrimination, in order to identify concerning trends and address inequalities.64 For defined entities, the employee experience survey data component of your workplace gender audit can assist in identifying which cohorts within your organisation are likely to report the experience of discrimination, and in what form.

In addition, centralising the reporting of discrimination incidents, as well as ensuring multiple safe channels for reporting (including one to leadership) can assist in identifying and tracking discrimination. You may also consider other avenues to collect qualitative data about employees’ experiences of discrimination, particularly for those from marginalised communities.65 Engaging with your staff, as well as relevant staff networks and experts from different communities can also assist you to approach this sensitively.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (July 2022), ’Table 5: Labour force status by Sex, Victoria - Trend, Seasonally adjusted and Original’, Labour Force, Australia, accessed 22 July 2022.

- ABS, ‘Labour force status by Sex’.

- Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC), Employee demographics and diversity, VPSC, accessed 21 July 2022.

- World Economic Forum (WE Forum), Global Gender Gap Report 2021, WE Forum, 2021.

- WE Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- J Cermak et al., Women in Leadership: Lessons from Australian companies leading the way, McKinsey & Company, 2017, accessed 22 July 2022; KPMG, She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap, KPMG, 2022, accessed 22 July 2022. J Cermak et al., Women in Leadership: Lessons from Australian companies leading the way, McKinsey & Company, 2017, accessed 22 July 2022; KPMG, She’s Price(d)less: The economics of the gender pay gap, KPMG, 2022, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), Men twice as likely to be highly paid than women, WGEA, accessed 21 July 2022; WGEA, The Gender Pay Gap, accessed 21 July 2022; R Cooper and E Hill, Research-informed principles for a gender equitable recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, University of Sydney, 2022, doi:10.25910/x3wh-pf20; N Cortis and G Meagher, ‘Recognition at Last: Care Work and the Equal Remuneration Case’, Journal of Industrial Relations, 2012, 54(3): 377-385, doi:10.1177/0022185612442278.

- ABS (June 2022), Labour Force, Australia, accessed 22 July 2022.

- WGEA, Gender segregation in Australia’s workforce, WGEA, accessed 21 July 2022. In fact, industrial segregation as a driver of the gender wage gap has grown by 11% since 2017 to contribute to 20 per cent of the gender wage gap in 2020 (KPMG, She’s Price(d)less, p 58.).

- Parliament of Australia, Gender segregation in the workplace and its impact on women’s economic equality, Australian Government, Finance and Public Administration References Committee, 2017, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Harmony Alliance, A Strategic Approach to Improving Employment Outcomes of Women from Migrant and Refugee Backgrounds in Australia [PDF 211KB], Harmony Alliance, 2019, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Harmony Alliance, Improving Employment Outcomes.

- Evans, Gari Yala (Speak the Truth): gendered insights, Jumbunna Institute of Education and Research and Diversity Council Australia, 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- C Frohmader, WWDA Response to Employment Issues Paper, Women with Disabilities Australia, 2020, pp 27-28, accessed 22 July 2022.

- S Waite, ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go? Employment Discrimination and Workplace Harassment against Transgender and other Minority Employees in Canada’s Federal Public Service’, Journal of Homosexuality, 2021, 68(11):1833-1859, doi:10.1080/00918369.2020.1712140; KK Dray et al., ‘Moving beyond the gender binary: Examining workplace perceptions of nonbinary and transgender employees’, Gender, Work & Organisation, November 2020, 27(6):1181-1191, doi:10.1111/gwao.12455; S Davidson, ‘Gender inequality: Nonbinary transgender people in the workplace’, Cogent Social Sciences, 2016, 2(1), doi:10.1080/23311886.2016.1236511.

- For the first time under Australian gender equality reporting legislation, organisations covered by the Act were required to provide data disaggregated not only by gender, but across a range of attributes. As outlined in the Introduction, the Commission will publish insights from this intersectional data in a companion report on intersectionality, to be released in 2023.

- This includes employees identifying as non-binary, agender and bigender. As many organisations are yet to collect meaningful data on gender diversity, we do not know the true gender composition of the public sector workforce, however we expect the real proportion of gender-diverse individuals to be higher than 0.1 per cent. This is based on recent international research that has found that over 50% of transgender and non-binary people hide their identity at work (D Baboolall and S Greenberg, ‘Being transgender at work’, McKinsey Quarterly, 10 November 2021, McKinsey & Company, accessed 22 July 2022; Kantar, DIVA, and Stonewall, The Diva Survey - LGBT+ Women and Non-Binary People’s Insight 2021, 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- S Sansonetti and E Davern, Women and Transport (European Parliament: Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs, 2021), 38-40, accessed 22 July 2022; Transport Canada, Minister Garneau highlights the roles women play in Canada’s transportation system: Transcript, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health (PMNCH), Women in Global Health, PMNCH, accessed 22 July 2022.

- OECD, Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators OECD, p 8, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Sansonetti and Davern, Women and Transport, pp 38-40.

- Sansonetti and Davern, Women and Transport, pp 38-40.

- Transport Canada, Minister Garneau highlights the roles women play.

- WGEA, Australia’s gender equality scorecard: Key results from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s 2020-21 employer census, February 2022, p 5, accessed 22 July 2022.

- NSW Public Service Commission, Workforce Profile Report 2020, Chapter 6: Gender, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Statistics Canada, Sex, Gender and Sexual Orientation, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Office for National Statistics, EMP01: Full-time, part-time and temporary workers (seasonally adjusted [dataset, 19 July 2022], United Kingdom, accessed 25 July 2022.

- T Jones, ‘Female-to-Male (FtM) transgender employees in Australia’ in T Köllen (ed) Sexual orientation and transgender issues in organizations: global perspectives on LGBT workforce diversity, Springer, Switzerland, 2016, pp 101-116, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29623-4_6.

- G Hunt and M Pelz, ‘Transgender Rights in Canada: Legal, Medical and Labour Union Activities’ in T Köllen (ed), Sexual orientation and transgender issues in organizations: global perspectives on LGBT workforce diversity, Springer, Switzerland, 2016, pp 133-147, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29623-4_8.

- NSW Public Service Commission, Workforce Profile Report 2021, Chapter 6: Gender, pp 36-44.

- UK Cabinet Office, Statistical Bulletin: Civil Services Statistics: 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Te Kawa Mataaho Public Service Commission, Gender representation in the Public Service, New Zealand, accessed 22 July 2022.

- WGEA, Women in Leadership, accessed 22 July 2022.

- S Devillard et al., The Power of Parity: Advancing Women’s Equality in Canada, McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey & Company Canada, 2017, p 54, accessed 22 July 2022.

- WGEA, Women in Leadership.

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Gender Balance on Australian Government Boards: Report 2020-21, Australian Government, 2021, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Deloitte, Progress at a snail’s pace: Women in the Boardroom, Seventh Edition, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Note that the Women on Boards commitment applies to Victorian courts and all boards, except for statutory offices or officers, small Crown land committees of management, unpaid cemetery trusts, and school councils. It also does not apply to universities. The Victorian Government also has a target of having at least 50 per cent women councillors and mayors in local government by 2025 (Victorian Government, Women on Boards Commitment, accessed 25 July 2022; Local Government Victoria, Women Leading Locally, Victorian Government, accessed 25 July 2022..

- Statistics Canada, Proportion of women and men employed in occupations, annual [dataset, 7 January 2022], accessed 22 July 2022.

- Office for National Statistics, Understanding the gender pay gap in the UK, United Kingdom, 2018, accessed 22 July 2022.