Introduction

Flexibility and leave are important enablers of gender equality for organisations across Australia.191 Flexibility includes arrangements such as working remotely, working part-time, working more hours over fewer days, job sharing, shift swapping, and flexible start and finish times. Leave entitlements include parental leave, carers leave, purchased leave and family violence leave.

Attracting and retaining diverse talent is crucial to future-proofing workplaces and the economy more broadly and making workplaces more flexible and responsive to the needs of employees is an important way of achieving this.192 The uptake of paid parental leave and carers leave by both parents, as well as access to family violence leave, play a particularly important role in supporting greater economic security by enabling women to remain in the workforce.193

Key issues: Why was this measured?

Workplace flexibility is desirable

Research shows that workplace flexibility is a highly desirable feature of Australian workplaces194 with employees increasingly expecting organisations to have moved away from traditional workplace models.195 This has been magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to a rethink of what it means to 'go to work'.196 Unsurprisingly, the economic, health and social benefits associated with flexibility in work patterns have seen Australians want to continue to have the option to work from home.197

Research reported in 2021 found that Australian women were more likely than men to request to work from home in order to accommodate the higher burden of unpaid domestic and care responsibilities.198 Men were more reluctant to request flexibility as a result of masculine norms and because of perceived or actual impact on their career progression.199

Parenthood stalls career progression for women

Women’s transition due to parenthood from full-time work to either part-time work or leaving the paid workforce altogether stalls women’s career progression.200 This has been identified as contributing to 20% of the gender pay gap.201

Australian data also shows that women who experience intersecting forms of inequality are more likely to leave the workforce after having children. This trend is apparent for migrant and First Nations mothers, as well as mothers with disability, mothers caring for others with disability and young mothers.202

Women do most of the unpaid domestic and caring work

Women in Australia are 3.5 times more likely to have spent 30+ hours on unpaid domestic work per week, compromising their ability to participate in the formal economy to their full capability.203

The recently published results of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) Survey found housework is the largest form of unpaid work, averaging roughly 10 hours per week, followed by caring for one’s own children.204 Additionally, more than 12% of Australian women and 9% of men care for an elderly person or a person with disability, usually a family member. In 2018, 7 in 10 primary carers of elderly people or people with disability were women.205

Family violence is gendered and intersectional

Research has found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 32 times more likely to be hospitalised for family violence than non-Indigenous people,206 that one in 3 migrant and refugee women have experienced family violence,207 and that people with disability are almost twice as likely to have experienced family violence than people without disability.208 We also know that these individuals face more barriers to reporting family violence and accessing support services.209

Research indicates that leave is an important element among a range of workplace responses that can enable victim-survivors of family violence to maintain paid employment.210 Family violence leave, especially when paid, affords victim-survivors financial security, while allowing them time to access support, attend court appointments, move house, and recover from violence and abuse.211

How was this indicator measured?

Organisations covered by the Act were asked to provide data on the following as at 30 June 2021:

- the proportion of employees utilising formal flexible work arrangements (not including mandatory working from home periods due to the COVID-19 pandemic) disaggregated by gender, classification and employment basis

- the number of senior leaders utilising flexible work arrangements, disaggregated by gender and the type of flexible work arrangement. 212

In addition, they were asked to provide data on the following for the period between 1 July 2020 and 30 June 2021:

- the proportion of employees who had taken either paid and unpaid parental leave, disaggregated by gender, classification, and length of leave, and the number of people who exited the defined entity during a period of parental leave, disaggregated by gender

- the number of people accessing family violence leave and carers’ leave over the same period, disaggregated by gender.

In addition, employees of defined entities were invited to participate in a standardised employee experience survey. Organisations were surveyed separately, and the results were reported to the Commission as percentages of respondents. Items with fewer than 10 responses were suppressed to protect respondents’ privacy.

The Commission used this data to understand:

- employee views as to whether use of flexible work arrangements or having family or caring responsibilities acts as a barrier to success

- whether employees believe there is support and a positive culture in the workplace with respect to employees with flexible work arrangements or family or caring responsibilities

- employee uptake of flexible work arrangements.

What was found: Key data insights

Formal flexible working arrangements

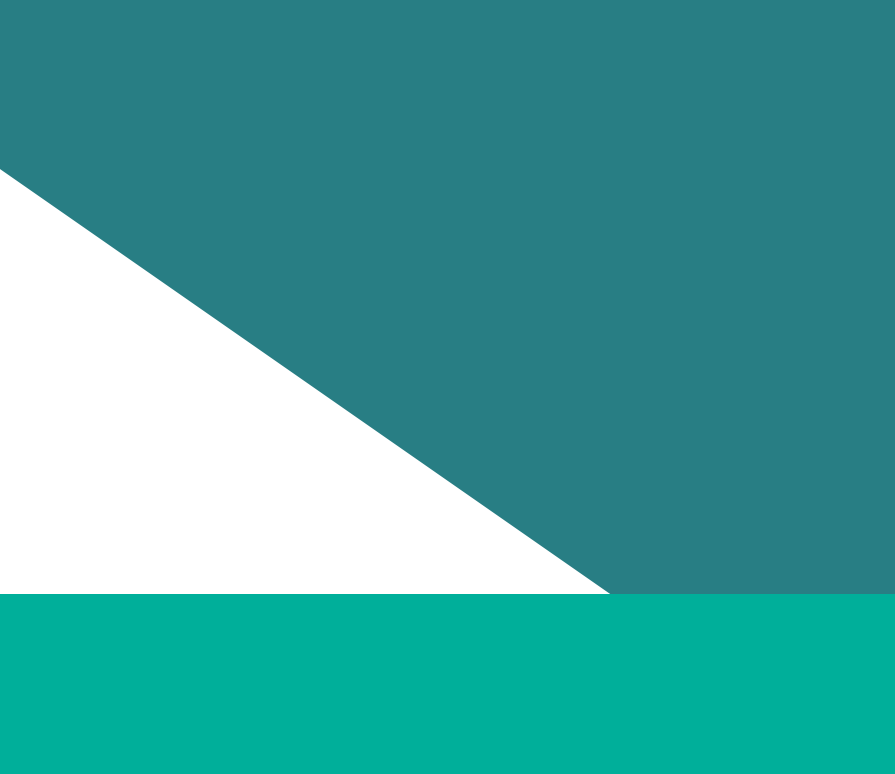

As Figure 5.1 shows, approximately one in 4 workers in organisations covered by the Act had formal flexible working arrangements in place. At the time of data collection, formal flexible work arrangements were most common within the Victorian Public Service, universities, local government and public health care industry groups. They were least common within the arts, finance and insurance, and the transport industry groups.

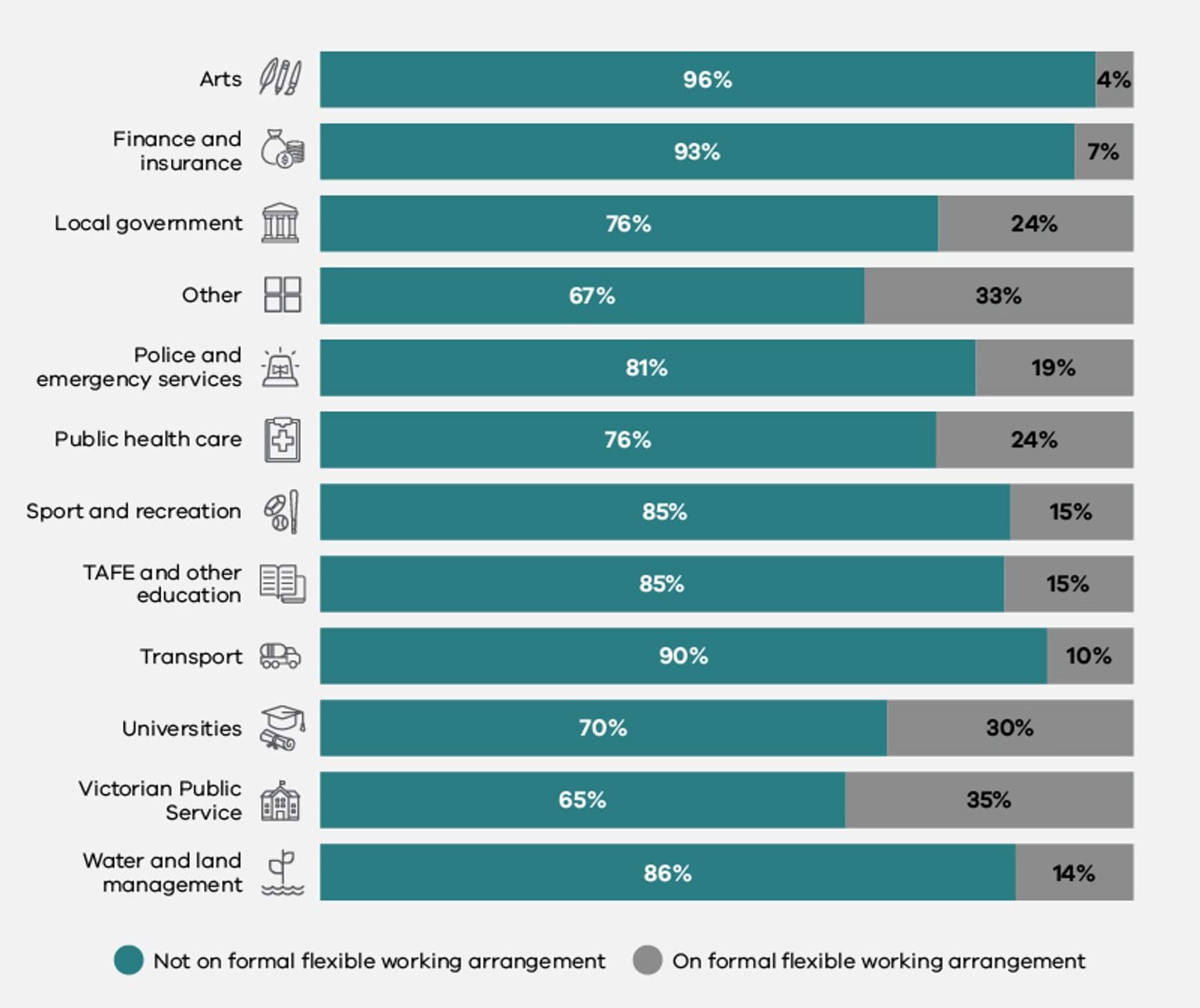

As at June 30 2021, across all defined entities, women comprised 77% of those with formal flexible work arrangements. Men comprised 22% and people of self-described gender comprised 0.1%.

As Figure 5.2 shows, at the industry group level, women with formal flexible work arrangements outnumbered men in all but one industry group. Transport was the only sector where more men than women were accessing formal flexible working arrangements.

At the industry group level, people of self-described gender comprised up to 1.8% of those using formal flexible work arrangements, with the Arts sector showing the highest level of uptake among this group.

Part-time work and job sharing

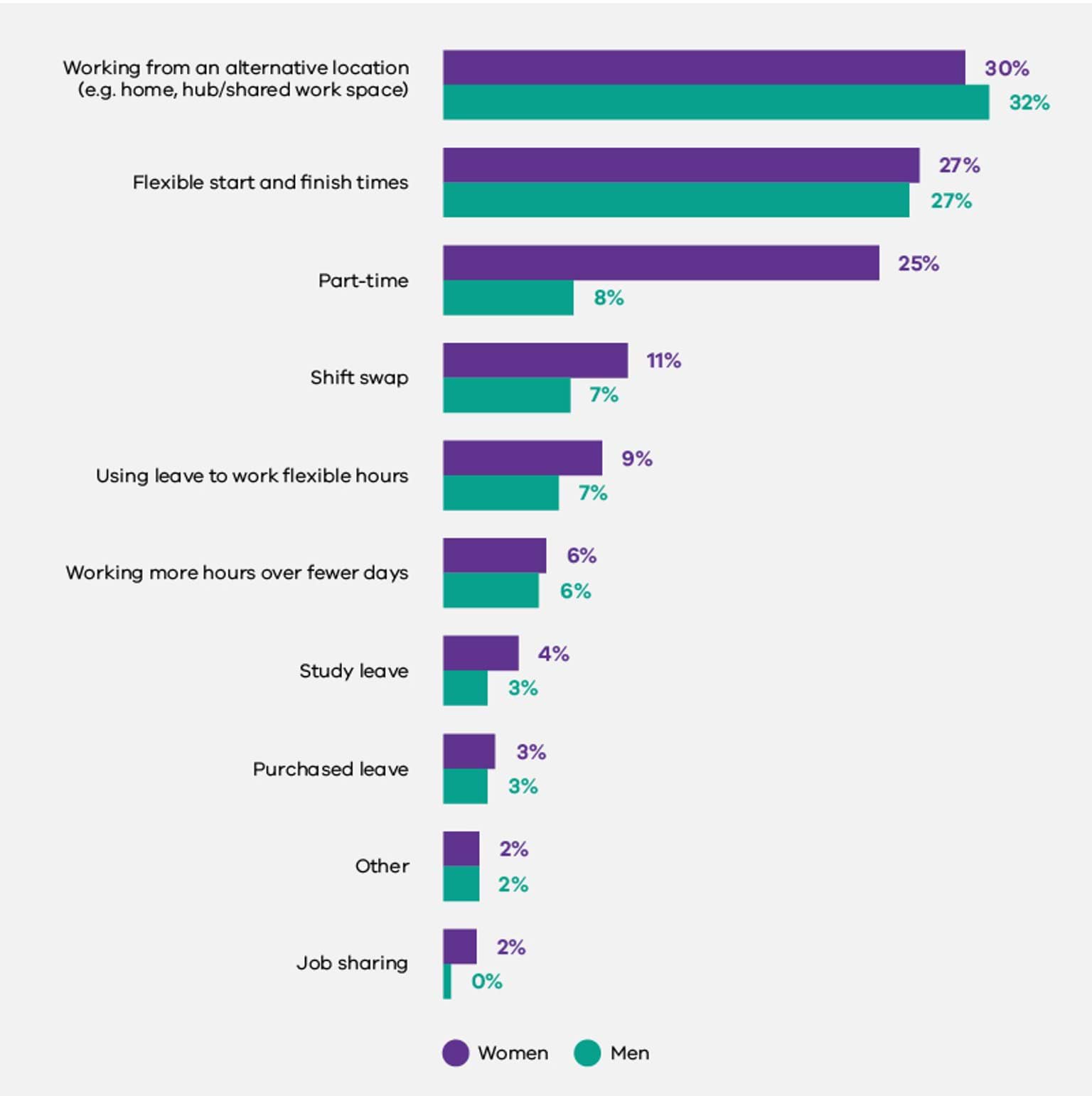

As shown in Figure 5.3, among survey respondents, most types of flexible work were accessed fairly evenly by women and men. This included working from home (or an alternative remote work location) and utilising flexible start and finish times, which were the types of flexible work arrangements most frequently accessed by survey respondents. However, women were 3 times more likely to report that they worked part time.

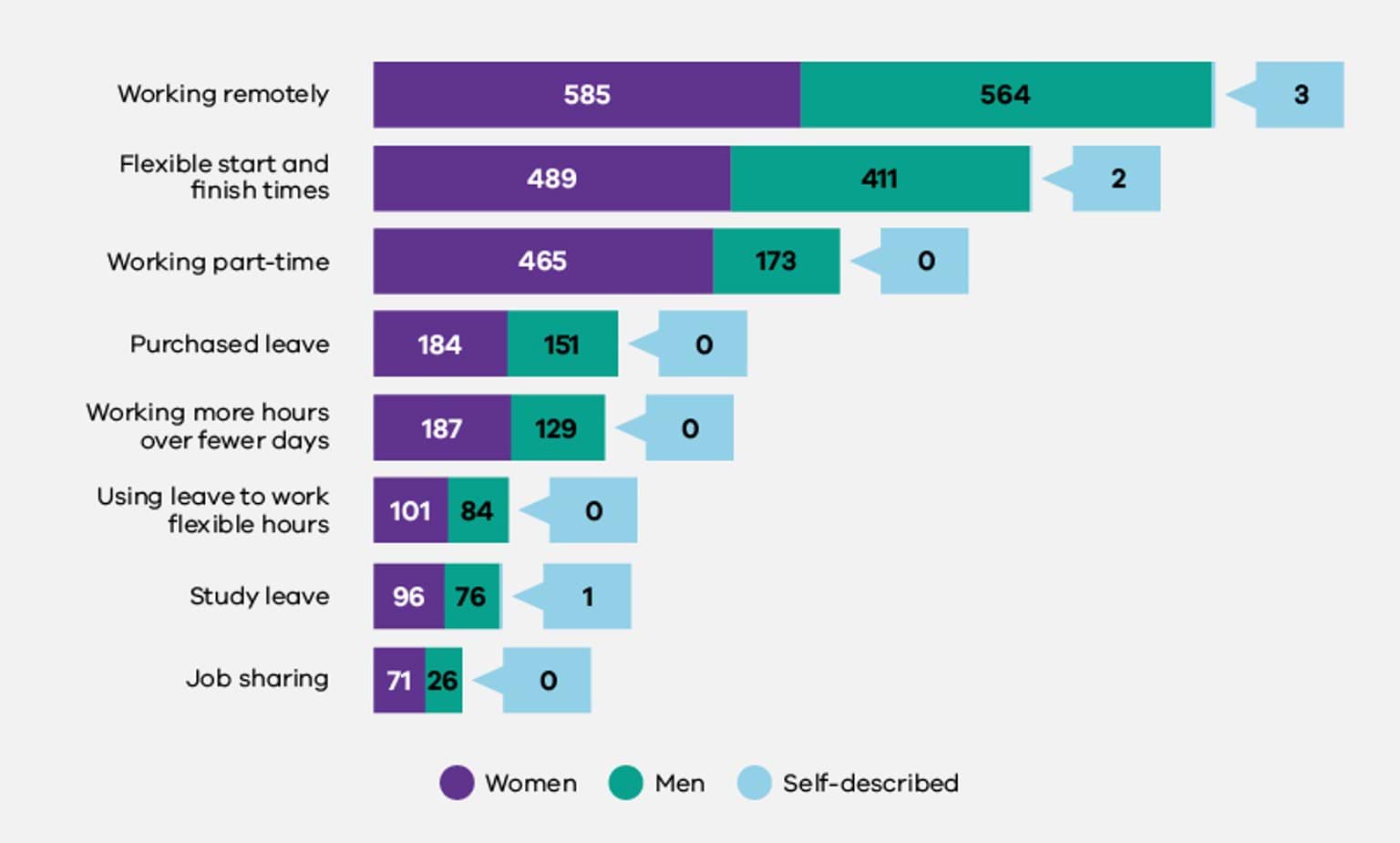

As shown in Figure 5.4, below, the types of flexible work most frequently used by senior leaders were remote work and flexible start or finish times. These were accessed almost equally by women and men. However, two types of flexible work were disproportionately utilised by women in senior leadership roles: part-time work and job sharing. These types of flexible work arrangements are more likely to entail a financial penalty than others and can thus contribute to gender pay gaps.213

Parental leave

Across all defined entities covered by the Act, women comprised 79% of parental leave takers. People of self-described gender comprised 0.1% of parental leave takers.214

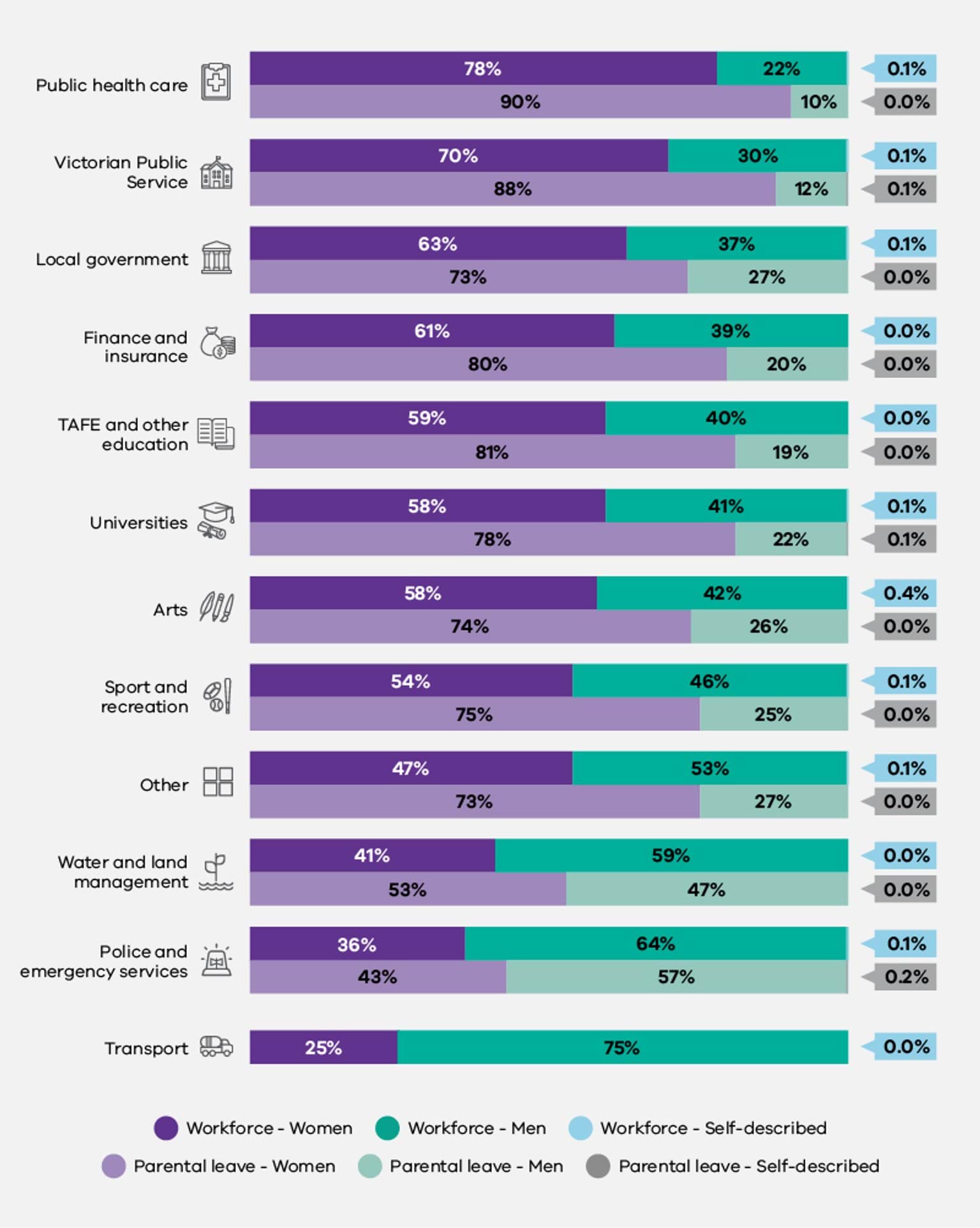

As can be seen in Figure 5.5, below, in 9 of the 11 industry groups, women comprised more than 70% of parental leave takers. Within the public health care and Victorian Public Service industry groups, nearly 9 in 10 parental leave takers were women. The industry groups with the highest proportion of men taking parental leave were police and emergency services (57%) and water and land management (47%).

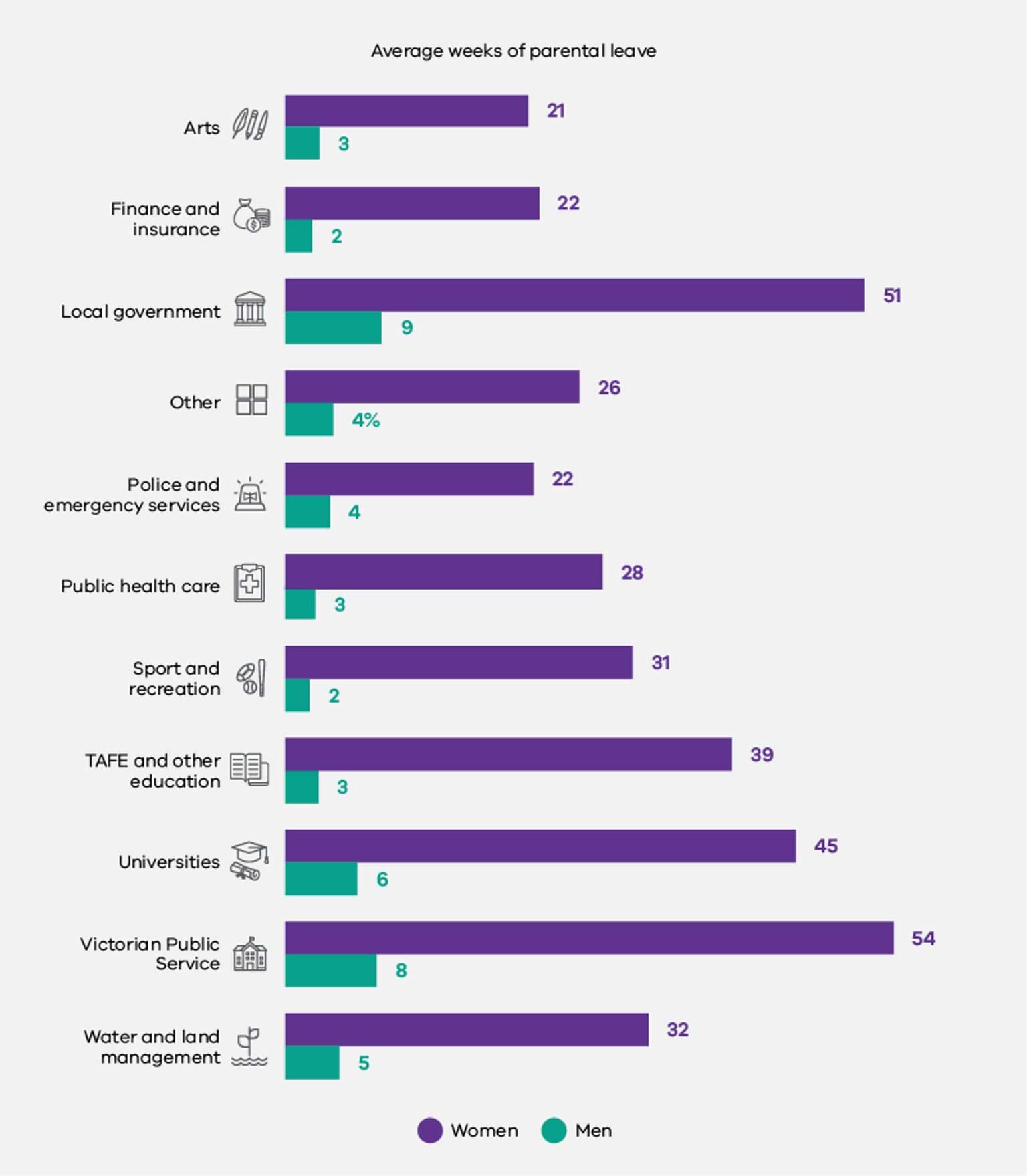

The average woman who took parental leave accessed 20 weeks of paid leave and 22 weeks of unpaid leave, while the average man took 4 weeks of paid and 2 weeks of unpaid parental leave. The average person of self-described gender took 5 weeks of paid parental leave and 6 weeks of unpaid parental leave.

As set out in Figure 5.6, below, at the industry level, durations varied noticeably, with women’s parental leave lasting between 6 and 14 times longer than men’s. Women’s and men’s parental leave durations were closest in the police and emergency services industry group and in local government, while they were farthest apart in the sport and recreation industry group and the TAFE and Other Education industry groups.

Figure 5.7 shows that across all defined entities, women comprised 94% of exits during parental leave (both voluntary and involuntary). Comparatively, 6% of exits during parental leave were men and 0.2% were people of self-described gender.

Family violence leave

The vast majority (88%) of those who accessed family violence leave in organisations covered by the Act were women, while 11% were men, and 0.2% were people of self-described gender. Given the gendered nature of family violence these findings are unsurprising.215

Carer's leave

Of those accessing carer’s leave in defined entities, the majority were women, at 68%. Men comprised 32% of those accessing carer’s leave, while 0.1% were people of self-described gender. This unequal distribution of carer’s leave reflects broader evidence that women in the paid workforce remain more likely than men to provide care to others.216

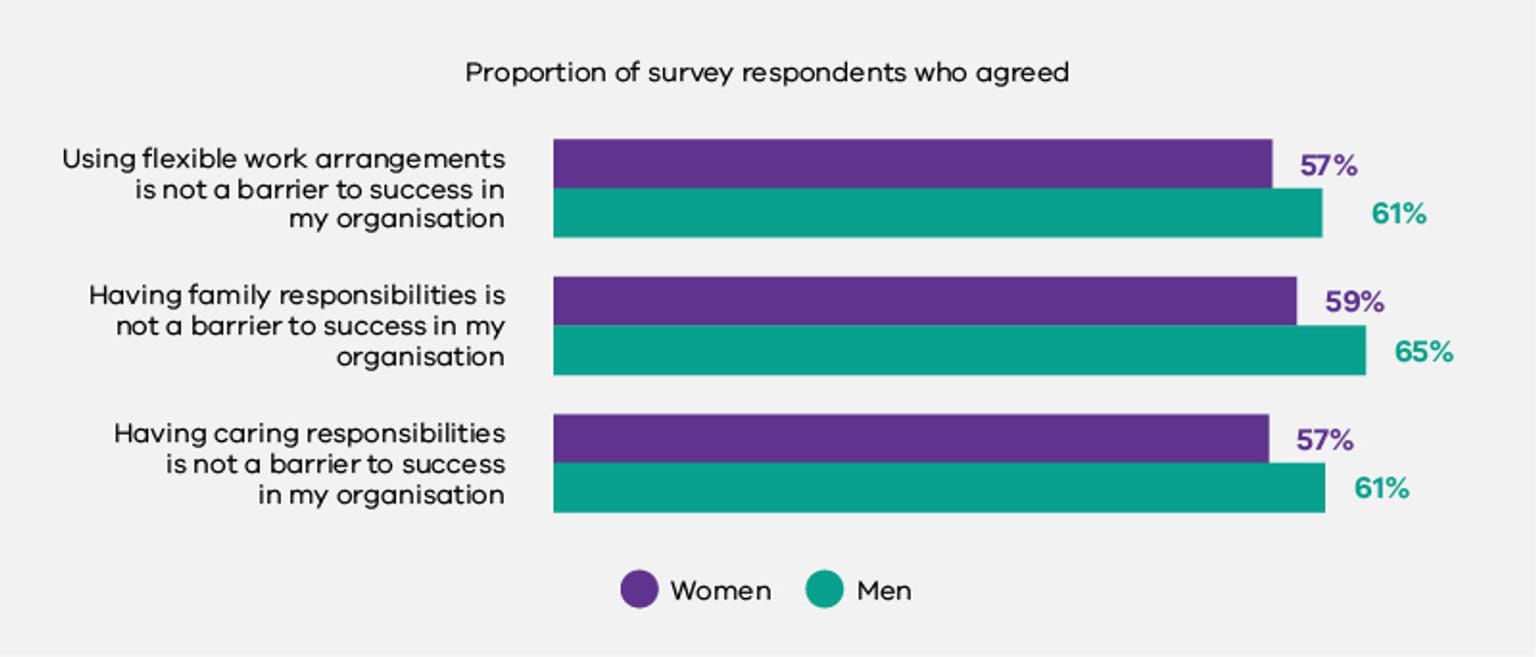

Flexibility and caring as barriers to success

As shown in Figure 5.8 below, the majority of survey participants believed that flexible work, family responsibilities and caring responsibilities were not barriers to success in their workplace, regardless of gender. However, women’s agreement rates were consistently lower than men’s in relation to these questions.

Discussion

The Victorian public sector, local councils and universities are nation-wide leaders in acknowledging the role flexible work and family violence leave policies can play in achieving gender equality.217 In light of this policy leadership across the public sector, the Commission’s focus is on promoting equitable uptake of these entitlements.

The 2021 workplace gender audit data reinforced existing research, which warns that access to flexible work alone does not necessarily result in equitable uptake among employees, nor does it ensure equitable career outcomes for those who adopt flexible working practices.218 Rather, policy implementation and organisational culture are critical to ensuring flexible work does not disadvantage those who access it, nor perpetuate gendered inequalities around both paid work and caring.219

While flexible work arrangements and parental and carers’ leave entitlements are critical for women to manage the competing demands of paid and unpaid work, it is important that uptake of these entitlements is balanced across genders. Not only does an imbalance widen the gender pay gap, but it reinforces gender stereotypes and norms. Therefore, while Victoria’s policy leadership is commendable, the gender imbalance in formal flexible working arrangements visible in the Commission’s data suggests defined entities must continue monitoring the gendered impacts of flexible working arrangements on women’s disproportionate load of unpaid work and care, as well as the associated consequences for women’s career progression.

Over the past decade, family violence leave has been identified as an important support measure to assist victim-survivors of family violence to maintain paid employment and escape harm.220 Collecting and responding to data about the uptake of family violence leave will enable defined entities to ensure they are supporting all employees experiencing family violence. This data will also supplement the limited existing formal data about whether paid family violence leave can enable greater employee wellbeing, as well as retention and progression. Data collection on this indicator may also be useful for other jurisdictions and sectors to consider the value of paid family violence leave.

Paid leave is particularly important to address the acute financial insecurity often faced by victim-survivors. A 2017 report estimated that, in Australia, the average financial cost to the victim-survivor of intimate partner violence, specifically, was $27,000.221 In May 2022, the Fair Work Commission released a provisional decision to include 10 days paid family violence leave in all Australian awards.222 To date, this decision has not yet been finalised; all Australian employees are currently entitled to 5 days unpaid family violence leave per year.223

Recommendations

Organisations covered under the Act should aim to move towards systems and cultures where flexibility is embedded and is not a barrier to progression, and where no value judgements are attached to the flexibility needs of employees.

To enable a workplace to understand whether they are moving towards that future, organisations should ensure they are collecting a holistic range of quantitative, qualitative and evaluation data including:

- formal and informal leave arrangements

- evaluation data relating to programmatic efforts focused on:

- preventing exits during parental and carer’s leave

- supporting more fathers, carers and guardians to take up parental leave and flexible work arrangements

- supporting managers to manage flexible and hybrid teams

- monitoring career progression of leave takers

- feedback from all levels of the organisation about how flexible work practices can be improved.

Workplace gender audits completed under the Act will support this data collection.

References

- Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA), Flexible work, accessed 25 July 2022.

- WGEA, Flexible work.

- KPMG, Enhancing work-life balance: A better system of Paid Parental Leave, KPMG, 2021, accessed 25 July 2025; Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) Fact sheet: Domestic and family violence - a workplace issue a discrimination issue, AHRC, 2014, pp 2-4.

- Victorian Equal Opportunity & Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC), Rebuilding flexible workplaces – Lessons for the post-COVID workplace’, May 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- PwC, Hopes and Fears 2021, March 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- VEOHRC, Rebuilding flexible workplaces.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey, February 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- ABS, Household Impacts of COVID-19 Survey.

- A Borgkvist, ‘It Would be Silly to Stop Now and Go Part-Time: Fathers and Flexible Working Arrangements in Australia’, in M Grau Grau et al. (eds) Engaged Fatherhood for Men, Families and Gender Equality. Contributions to Management Science, Springer, Cham, 2022, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-75645-1_13.

- L Jones, Women’s progression in the workplace, Global Institute for Women’s Leadership & Government Equalities Office, UK, October 2019, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Jones, Women’s progression in the workplace.

- J Baxter, Employment characteristics and transitions of mothers in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Australian Government, 2013, accessed 25 July 2022.

- ABS, Unpaid work and care: Census, 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- R Wilkins et al., The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey: Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 19, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, the University of Melbourne, accessed 25 July 2022.

- ABS, Disability Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2019, accessed 25 July 2022; Department of Health and Human Services, Recognising and supporting Victoria’s carers Victorian carer strategy 2018-22, State of Victoria, 2018, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: Continuing the national story 2019, Australian Government, 2019, accessed 25 July 2022.

- M Segrave et al., Migrant and refugee women in Australia: The safety and security study, Monash University, 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- AIHW, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia.

- AIHW, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia.

- R Weatherall et al., ‘Safeguarding women at work? Lessons from Aotearoa New Zealand on effectively implementing domestic violence policies’, Journal of Industrial Relations, 2021, 63(4):568-590, doi:10.1177/0022185621996766.

- Weatherall et al., Safeguarding women at work?.

- For the first time under Australian gender equality reporting legislation, organisations covered by the Act were required to provide data disaggregated not only by gender, but across a range of attributes. As outlined in the Introduction, the Commission will publish insights from this intersectional data in a companion report on intersectionality, to be released in 2023.

- L Ruppanner and J Meekes, Flexible work arrangements help women, but only if they are also offered to men, The Conversation, 8 March 2021, accessed 25 July 2022; DR Eikhof, ‘A double‐edged sword: twenty‐first century workplace trends and gender equality, Gender in Management: An International Journal, 27(1):7-22, doi:10.1108/17542411211199246.

- The Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA) gathers data from private sector organisations with more than 100 employees. In 2020-2021, its data showed that women accounted for 88% of the total primary parental leave takers, as opposed to men accounting for 12% (WGEA, Australia’s gender equality scorecard: Key results from the Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s 2020-21 employer census, 2022, accessed 25 July 2022). Australia-wide in 2016, the Australian Bureau of Statistics recorded women taking 95% of primary parental leave, with only 1 in 20 fathers accessing this leave type (ABS, One in 20 dads take primary parental leave [media release], 19 September 2017, accessed 25 July 2022.) These statistics do not represent direct comparison with the Commission’s data, as the figures only include primary parental leave, whereas we measure all parental leave. However, in combination, all 3 datasets demonstrate that parental leave in Australia continues to be highly gendered both in the public and private sectors.

- Our Watch, Quick facts, Our Watch, accessed 25 July 2022; AIHW, Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia, 2018, Australian Government, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Informal carers, OECD, 2021, accessed 25 July 2022.

- In 2021, the Victorian Government made flexible working the default position for all public service employees, including executives. Further, family violence leave has been included in all Victorian public sector enterprise agreements since 2015, meaning public sector employees (including nurses and teachers) have access to 20 days of paid family violence leave, an entitlement reflected (and in some cases exceeded) in almost all Victorian local council and university enterprise agreements (Tim Pallas MP, Victoria leads the way on paid family violence leave [media release], Victorian Government, 11 April 2022, accessed 25 July 2022; Australian Services Union (ASU), Family Violence Leave’, ASU, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Eikhof, A double‐edged sword.

- Eikhof, A double‐edged sword.

- Weatherall et al., Safeguarding women at work?; We Are Union, Understanding family violence as a workplace issue: Your guide, Victorian Trades Hall Council, accessed 25 July 2022.

- PwC, A high price to pay: the economic case for preventing violence against women, 2015, accessed 22 July 2022.

- Fair Work Ombudsman, Paid family and domestic violence leave in awards, Australian Government, 2022, accessed 25 July 2022.

- Fair Work Ombudsman, Paid family and domestic violence leave in awards.

Updated