- Date:

- 2 July 2025

You can download the Word version of the Insights report: sexual harassment on the right-hand side of the page above the menu.

Introduction

Introduction

Sexual harassment is still a significant problem across the Victorian public sector. This report tells duty holders under the Gender Equality Act 2020 what they must do to address it.

The Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector (the Commission) is the only regulator requiring Victorian public sector organisations to regularly report on sexual harassment.

Using our unique dataset, we looked at data from 2021 and 2023 workplace gender audits. This report shows what we found and gives you practical steps to take. It builds on our 2021 Baseline Report and helps duty holders meet their legal requirements.

This report is for workplace leaders, HR staff and people working towards gender equality. It focuses on:

- what our data shows about sexual harassment in public sector workplaces

- where the biggest risks are and why

- what effective action looks like in workplaces

- how new laws should drive workplace responses.

We used data from duty holders and research from across Australia. The main goal is to help you take action. We show you practical steps you can take to prevent and respond to sexual harassment in public sector workplaces.

Our current data has limits. The majority of the data in this report refers to women and men. Not all duty holders provide data on people who self describe their gender, so often the sample size is too small to analyse meaningfully. Where we have good data, we include findings for employees of self-described gender.

Use this report to check your progress, improve your response, and make safer workplaces for everyone.

What is workplace sexual harassment?

The law defines sexual harassment in the Sex Discrimination Act 1984.

A person sexually harasses another person if they:

- make unwelcome sexual advances or ask for sexual favours, or

- do other unwelcome sexual behaviour when a reasonable person would expect the harassed person might feel offended, humiliated or scared.

According to the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) (2022:22), workplace sexual harassment includes:

- sexual comments or jokes

- personal questions about someone’s private life or how they look

- repeated unwanted invitations to go on dates

- pressure for sex

- inappropriate staring

- unwelcome touching, cornering or hugging

- sexual messages using technology

- actual or attempted rape or sexual assault.

Who is at risk?

Even though people know more about this issue and laws have changed, sexual harassment is still a common experience for many Australian workers, especially women.

One in three Australian workers experienced sexual harassment in the past five years (AHRC 2022b:13). But fewer than one in five made a formal complaint, and one in four of those who did, said nothing happened to the person who harassed them (AHRC 2022b:14).

While people of all genders may experience sexual harassment, most people who do the harassing are men and most victim survivors are women. The Australian Human Rights Commission found that in 2022, 77% of people sexually harassed at work were harassed by a man (AHRC 2022b:58)

As well as gender inequality, the Speaking from Experience report (AHRC 2025a) highlights that intersecting forms of disadvantage increase the risk and severity of workplace sexual harassment. These can include being a First Nations person, visa status, race, migration background, gender identity, disability, age and economic security (see also AHRC 2020; Cho and Segrave 2023; CGEPS 2023; Robinson et al. 2024). Workers in insecure employment or with limited access to social or legal support are often specifically targeted by harassers who exploit these vulnerabilities (AHRC 2025a).

Other power differences in the workplace can also be exploited, and people at all levels of seniority can be targeted. Alongside junior staff, women supervisors also commonly experience sexual harassment (AHRC 2020:140). Perpetrators of harassment often target colleagues working at the same level.

The costs of sexual harassment

Workplace sexual harassment causes serious harm. The Australian Human Rights Commission’s 5th national survey on sexual harassment found that, of those who had experienced workplace sexual harassment:

- 67% experienced negative mental or emotional health

- 57% experienced drops to their self-esteem and confidence

- 62% had reduced job satisfaction

- 53% had reduced organisational commitment (AHRC 2022b:98).

Sexual harassment also affects people who see it happen, victim survivors’ families and friends, and even the people who do the harassing (AHRC 2020:275–280). Research shows that sexual harassment hurts all women by undermining their authority in the workplace and reinforcing harmful stereotypes about women (MacKinnon, 1979).

For employers and the economy, the cost is huge. In 2018, Deloitte found that sexual harassment cost Australia $3.5 billion each year. These costs included lost productivity, reduced wellbeing, and impacts on health and justice systems. To avoid these costs, spending money on prevention makes sense (AHRC 2020:6).

Changes to laws and policies

Australia has done more to prevent and address workplace sexual harassment in recent years. This started with the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Respect@Work report in 2020, which made 55 recommendations. The federal government said it would implement all of them.

One of the biggest changes was creating a ‘positive duty’ under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984. This legal requirement means employers must actively prevent sexual harassment. The focus changed from just responding to complaints to creating safe workplace environments.

Other changes to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 include:

- a new ban on hostile workplace environments based on sex

- a lower standard for sex-based harassment (now ‘demeaning’ instead of ‘seriously demeaning’)

- more powers for the Australian Human Rights Commission

- standardised complaint timeframes (AHRC 2022).

The Fair Work Act 2009 was also updated to:

- define ‘sexual harassment’ and ‘sexually harassed at work’

- empowering the Fair Work Commission to make orders to stop sexual harassment

- clarify that sexual harassment can be a valid reason for dismissal (Smith 2023:16–17).

Non-disclosure agreements

In 2022, the Respect@Work Council made guidelines to stop the regular use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) when dealing with sexual harassment cases. NDAs can sometimes protect victim survivors’ privacy, but they can also:

- hide how big the problem is

- silence victim survivors

- stop senior leaders from knowing what’s happening

- let people who harass others keep doing it if they remain in the workplace or move to other jobs (AHRC 2022a:6).

Victoria is leading Australia with a recent promise to limit NDA use in workplace sexual harassment cases.

Technology-facilitated sexual harassment

As workplaces use more technology, new risks are appearing. Workplace technology-facilitated sexual harassment (WTFSH) is now a growing problem that organisations must prevent.

WTFSH includes harassment using phones, cameras, digital messages and other online tools (Flynn et al., 2024).

Research shows that it is often linked to:

- remote and hybrid work – which can blur personal and professional spaces (Flynn et al., 2024:27).

- online subcultures that promote sexist beliefs (Wescott et al., 2024)

- male-concentrated workplaces (Flynn et al., 2024:11).

People in a recent study said WTFSH feels like sexual harassment that you can’t escape. It spills into personal life (Flynn et al., 2024:27).

Examples include:

- using shared calendars to track where a colleague goes (Flynn et. al., 2024:68)

- taking screenshots during video calls without permission (Flynn et. al., 2024:68)

- sending too many emails or messages to gain unwanted attention (Flynn et. Al., 2024:30).

WTFSH isn’t just ‘misusing technology’. It is caused by the same things that cause other forms of violence against women – misogyny, hyper-masculine workplace cultures, and poor leadership (Flynn et al., 2024:11).

Worryingly, one in seven Australians admitted to perpetrating WTFSH, but fewer than half had faced a formal complaint (Flynn et al. 2024:13).

About our data

This report uses data from duty holders for the 2021 and 2023 workplace gender audits under the Gender Equality Act 2020. Duty holders must report this data to the Commissioner every two years. This is part of their requirement to develop gender equality action plans and report on progress.

Other regulators such as WorkSafe Victoria can respond to cases of sexual harassment when a complaint is made. But we are the only regulator requiring public sector organisations to regularly report on sexual harassment. Regular reporting holds organisations to account. It also supports duty holders to proactively drive change to reduce sexual harassment.

Duty holders can update their audit submissions if they identify ways to improve or correct their data. This can lead to changes in the underlying data used in our reports. As such, data in this report may be different from previous releases.

We use three types of data:

- Aggregated workforce data: Data already put together from organisations’ payroll and HR systems, shown mainly as headcounts. We used this for the 2021 audit (177 organisations that met quality standards).

- Unit-level workforce data: Anonymous individual employee data from organisations’ payroll and HR systems. We used this for the 2023 audit (257 organisations that met quality standards).

- Unit-level employee experience data: Anonymous individual data from the People matter survey1 for participating duty holder organisations in 2021 (106,069 people from 271 organisations) and 2023 (131,852 people from 276 organisations).2

Many public sector employees take the People matter survey, so small percentage changes can mean a large number of people have experienced a change.

Some of this audit data for each duty holder organisation is published on the Commission’s Insights Portal(opens in a new window) to support transparency, accountability and learning across the sector.

This report builds on our Baseline Report, which looked at 2021 data. Compared to 2021, the 2023 data includes more organisations and better data, especially from duty holders who were just starting their gender equality work in the first audit.

Where possible, we compared 2021 and 2023 data to find trends, track progress and highlight areas needing more attention. But there were some limitations:

- In 2021, some duty holders’ data was too poor quality to use.

- The 2021 audit happened during long COVID-19 lockdowns, which may have changed sexual harassment experiences and reporting.

- Many duty holders and researchers still only collect gender data as male/female or men/women, limiting analysis for people with diverse gender identities.

Where we had enough data, we included insights beyond just the categories of women and men.

This report also uses research from across Australia and specific sectors to help understand our results and give evidence-based recommendations.

Footnotes

- The People matter survey is an annual employee experience survey administered by the Victorian Public Sector Commission. In every Gender Equality Act reporting year, around 90% of duty holders use the People matter survey to fulfil the employee experience data component of their workplace gender audit. For more information on the People matter survey and its use in data insights, see the methodology section of Intersectionality at work(opens in a new window).

- Data in this report is not comparable to similar data published by the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC). VPSC collect data from all public sector organisations. We collect data from public sector organisations with more than 50 employees, as well as local councils and universities. The two Commissions’ workforce data collections are separate. And while we both use People matter survey data, we analyse a different selection of organisations. We also often make different calculations. As such, the results we publish are different. To learn more about recent data from the VPSC, visit the State of the public sector report(opens in a new window).

What our data shows

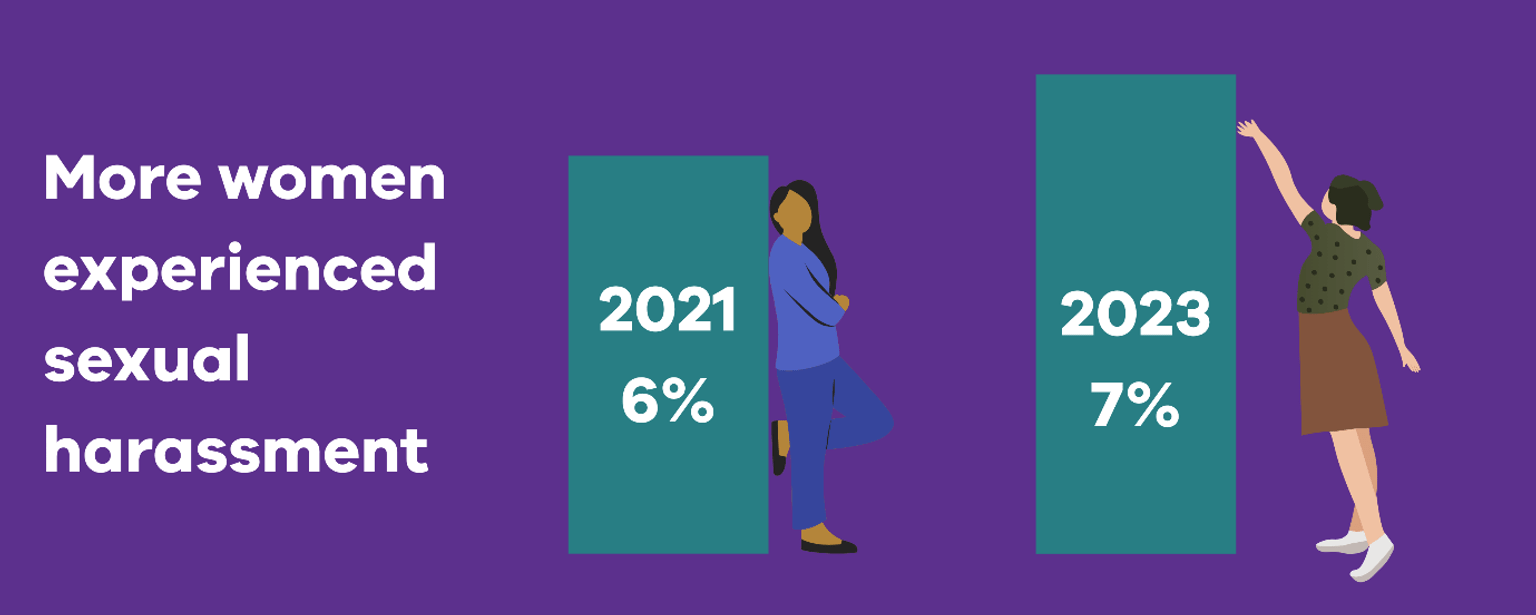

Overall, sexual harassment increased by 1% for women in 2023 compared to 2021 (up to 7%). For men it stayed the same (4%).

While these overall rates are lower than the national average1, no amount of sexual harassment is acceptable. Sexual harassment in the public sector may be lower because the workforce is more regulated and has higher public scrutiny than the private sector. But public sector workplaces can also have enabling factors such as hierarchical structures, areas with poor or highly masculine workplace cultures, and lack of commitment from leaders (McFarlane et al. 2025). Public sector workers are also often front-line staff who face higher risk of sexual harassment from patients or clients (Mikołajczak et al. 2024).

Industries that saw increases in the experience of sexual harassment for both women and men included arts (4% increase for both) and public health care (1% increase for both). In 2023, 8% of women and 5% of men in both arts and public health care said they experienced sexual harassment at work.

Only local government saw a decrease in sexual harassment for both women and men. In 2023, there was a 1% decrease for both – down to 6% for women and 4% for men.

Industries that saw decreases for women were police and emergency services (from 12% in 2021 to 10% in 2023), sport and recreation (down from 8% to 7%), transport (down from 14% to 9%), and water and land management (down from 5% to 4%).

People of all ages experienced sexual harassment, but younger people (15 to 24 and 25 to 34) had higher rates. In 2023, there was a 1.3% increase for women aged 15 to 24 (up to 15.4%) and a 1.5% increase for men in this age group (up to 5.6%).

First Nations women saw a 2.6% increase (up to 9.1% in 2023). The experience of sexual harassment for First Nations men also increased by 0.2% to 5.6% in 2023. For comparison, non-Indigenous women’s and men’s rates were 6.5% and 3.4%.

Both women and men with disabilities experienced higher rates of sexual harassment than those without disabilities. The experience of sexual harassment for women with disability increased slightly in 2023 (up to 11.8% – a 0.2% increase). The experience for men with disability decreased slightly (down 0.3% to 8.1%). Women and men without a disability had rates of 6.1% and 3.2%.

Sexual harassment increased for culturally and racially marginalised (CARM) women by 0.8% in 2023 (up to 6.2%). This rate is slightly lower than for non-CARM women, which increased by 0.1% (up to 6.7%). Our Intersectionality at Work(opens in a new window) report (2023: 64) discussed how we need more research on CARM women’s experiences. CARM women may face more barriers to reporting because of insecure work and visa conditions, cultural expectations about gender roles and attitudes to authorities, and different understandings of what counts as sexual harassment.

Thirty-nine percent of Victoria’s healthcare workers are born overseas, and healthcare workers experience high rates of sexual harassment in general (Mikołajczak et al. 2024:14). As such, this is a significant issue for public health care organisations in particular.

Bisexual women saw a 0.8% increase in sexual harassment in 2023 (up to 15.1%). The experience of sexual harassment for non-binary or gender diverse people increased by 1.6% (up to 15.6%) and for transgender men by 1.2% (up to 8.8%).

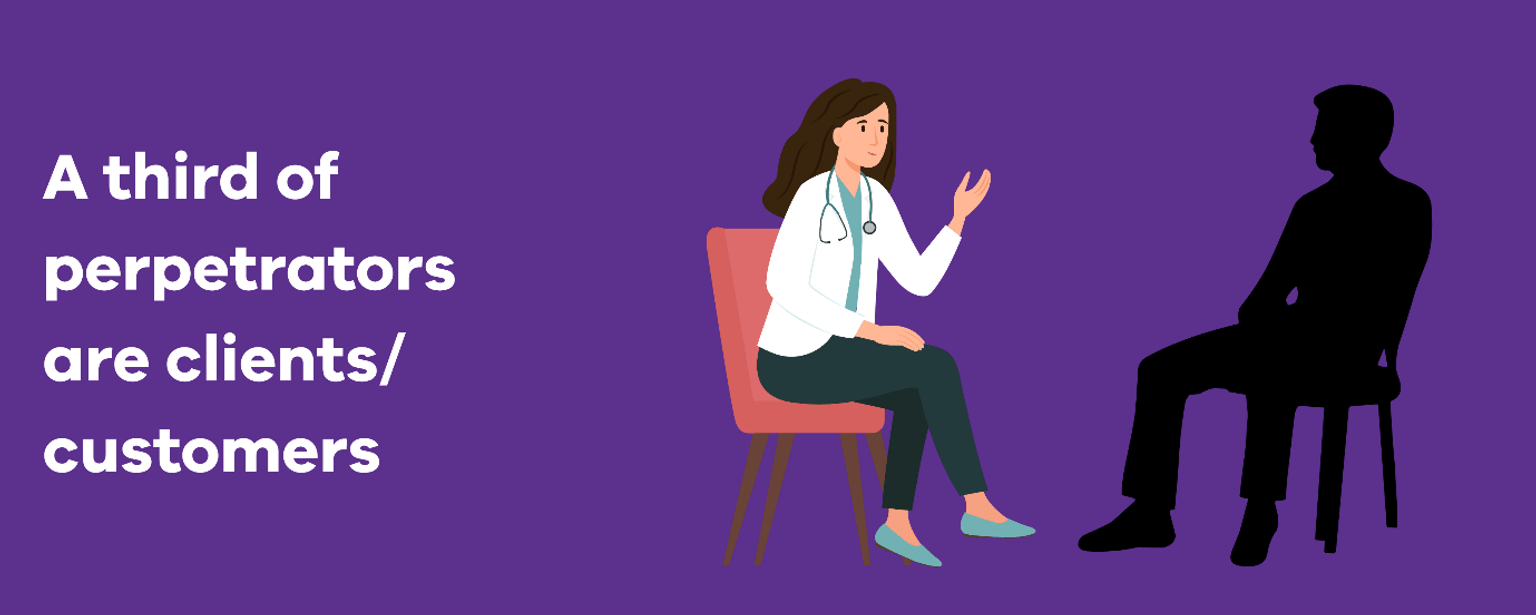

In both 2021 and 2023, most sexual harassment for people of all genders was perpetrated by a colleague. In 2021, 56% of women, 62% of men and 61% of people of self-described gender who reported harassment said a colleague did it. In 2023, these numbers went down to 48% of women, 61% of men and 51% of people of self-described gender.

In 2023, 37% of women said the person who harassed them was a client, customer, patient or stakeholder. This shows a 6% increase from 31% in 2021. As we discuss later, public-facing industries may need specific strategies to address this type of harassment.

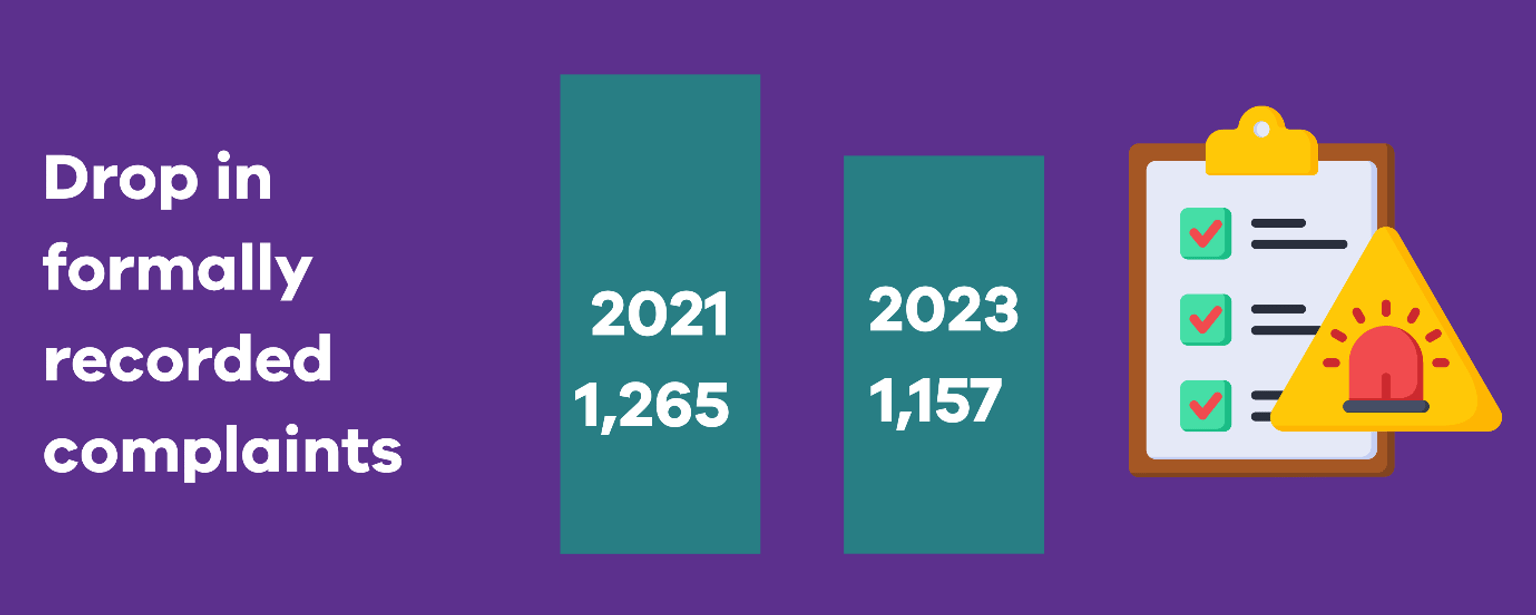

Overall, 2% more women and 1% more men said they made a formal sexual harassment report in 2023 compared to 2021 (from 5% to 7% for women and from 3% to 4% for men). But the number of sexual harassment complaints formally recorded by duty holder organisations went down from 1,265 in 2021 to 1,157 in 2023. Lived experience accounts from the Speaking from Experience (AHRC 2025a) report reveal that fear of job loss, visa cancellation, cultural stigma, and a lack of trauma-informed processes prevent many victim survivors from formally reporting.

Also, data on how satisfied complainants were with outcomes was mostly missing. In 2023, this data was missing for 844 (73%) incidents (compared to 1172 (93%) in 2021).

"Data collection on sexual harassment remains a key area for improvement. Duty holders must get better at collecting this important data. They also need to focus much more on reducing sexual harassment and increasing formal reporting. In 2023, only 60%2 of duty holders demonstrated compliance with the requirement to make progress on sexual harassment."

Dr Niki Vincent, Public Sector Gender Equality Commissioner

Footnotes

- In the most recent Australian Human Rights Council national survey, 41% of women and 26% of men reported being sexually harassed at work in the 5 years to 2022 (AHRC 2022:47).

- This figure was incorrectly reported as 40% when we first published this report. We have now updated this to the correct figure of 60%.

How to address sexual harassment

To eliminate sexual harassment, duty holders need ongoing, organisation-wide effort. This includes prevention, early intervention, employee support and strong leadership accountability.

Research shows that good responses must address not just individual behaviour, but the systems and culture that allow it to happen. Creating a safe and respectful workplace culture is also crucial to ensure your compliance with the new positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 for organisations to actively prevent workplace sexual harassment.

This section shows evidence-based actions organisations can take to understand, address and prevent sexual harassment.

Step 1: Collect and analyse your data

Many organisations don’t have the data they need to fully understand how much and what type of sexual harassment is occurring. This is especially true for informal reports, complaint outcomes, and how employees experience the system.

What data to collect

Your goal should be to collect data that shows:

- what is being reported, and where, including if incidents are more common in certain teams or locations

- how employees experience your systems and policies

- whether staff trust processes and feel safe using them

- what stops people from coming forward.

Data separated by gender, team, role, or other factors can help you spot trends that are otherwise easy to miss.1 Survey results(opens in a new window) can give valuable insights into trust, confidence and psychological safety.

Under the Gender Equality Act 2020, your workplace gender audit must include gender-disaggregated data. To understand the full picture of workplace sexual harassment, you should disaggregate data by additional factors. These might include visa status, disability, First Nations status, cultural background and LGBTIQA+ status. Collective qualitative insights to gain a more complete picture. This is crucial to revealing patterns of harm and barriers to reporting (AHRC 2025a). You can find recommendations for improving your intersectional data collection, analysis and interpretation in our Intersectionality at Work (opens in a new window)report (CGEPS 2023: 96-100).

How to analyse your data

Sexual harassment isn’t just individual bad behaviour – it’s a form of violence against women.

The Respect@Work report (AHRC 2020) and the Change the Story framework (Our Watch 2021) highlight that sexual harassment has the same causes as other forms of violence against women. These include:

- power imbalances

- rigid gender roles

- disrespect

- inequality in decision-making.

To understand how sexual harassment shows up in your workplace, use data from both your workplace gender audit and employee experience survey. Key areas to look at include:

- where incidents occur

- what types of sexual harassment

- why incidents may not be reported

- whether staff feel safe to raise concerns

- how confident people are in your reporting processes.

When looking at your data, separate sexual harassment by co-workers from sexual harassment perpetrated by members of the public, clients or patients. You may need different strategies to address these different types, especially for prevention.

Understanding the reporting gap

Progress doesn’t always mean fewer complaints. Formal complaint numbers rarely tell the full story. More reporting may mean greater trust in your systems. Fewer reports could mean either better prevention or less confidence in reporting.

People may choose not to report because they fear negative consequences, don’t trust the system, or feel unsure about what counts as sexual harassment.

Research shows this gap between policy and real experience. For example, the South Australia Police Review (2016) found that even with formal systems in place, many staff felt reporting was unsafe or pointless. The Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission’s (2015:12) review of sexual harassment in Victoria Police also showed how women felt blamed when they spoke up. Formal reporting was sometimes seen as being disloyal to ‘the team’. The Respect@Work (AHRC 2020) report found similar concerns across Australian workplaces.

This is why you must use both your workforce data (number of formal reports), and your employee experience data (anonymous accounts from people who experienced workplace sexual harassment and why they didn’t make a formal complaint) to understand what’s really happening. Employees may report sexual harassment to their manager, but when it’s handled at the team level, senior leadership may not know. This can create big data gaps that stop you from understanding the full picture of sexual harassment in your workplace.

To find gaps in your organisation, consider:

- If employees are reporting experiences of sexual harassment to their direct manager, are these reports being formally documented, and do you know how these complaints are being managed?

- Do employees understand how to report and what happens next?

- Are responses consistent, confidential and person-centred?

- Is culturally safe and trauma-informed support available?

- What do informal feedback, survey results or focus groups show about trust in your systems?

Understanding these gaps helps you build systems that staff are more likely to use – and that are more likely to give safe, fair outcomes.

Sexual harassment from patients and clients

Public-facing industries face particular challenges with sexual harassment. Workers in health care, emergency services and local councils can experience sexual harassment from patients or clients as well as co-workers. This type of sexual harassment often goes unreported.

Healthcare workers are at a higher risk of experiencing sexual harassment than other workers. This is because they provide direct care, often involving physical contact and working alone with patients (Mikołajczak et al. 2024).

Recent evidence from Victorian healthcare workers found that 70% experienced aggression, violence or abuse from patients, and 52% of sexual harassment in the public healthcare sector was done by clients, customers, patients or stakeholders (Mikołajczak et al. 2024:8,10).

However, healthcare workers often don't report sexual harassment from patients (Gabay and Tikva 2020; Mikołajczak et al. 2024). One reason for this is that healthcare workers often work in isolation and there are no witnesses (Mikołajczak et al. 2024:28). Many are also taught to prioritise patient needs over their own safety, and others believe it is ‘part of the job’ that they should accept, or fear it might affect their career if they complain about patients (Mikołajczak et al. 2024). Additionally, organisations often treat violent behaviour from patients as ‘challenging behaviour’ rather than unacceptable harassment (Mikołajczak et al. 2024:13).

The Australian College of Nurses (2020) says health organisations must:

- create a culture of zero-tolerance of sexual harassment of nurses by patients

- support nurses to report all sexual harassment without fear of retaliation or blame

- educate and train nurses to be active bystanders and understand their responsibilities to report inappropriate behaviour.

Step 2: Use a risk-based approach to prevention

The Workplace Gender Equality Agency (2023) recommends using a risk-based approach to find and reduce sexual harassment risk factors early.

Key risk areas include:

- physical spaces – such as isolated work areas or poor visibility (Safe Work Australia 2023:25–26)

- work systems – including informal cultures, rigid power structures or unclear reporting pathways (Safe Work Australia 2023:24–25)

- workplace characteristics – such as male-heavy teams or lack of diversity in leadership (WGEA 2023).

Tips for public health care settings

- Healthcare specific risks include:

- working alone with patients in private spaces (examination rooms, patient homes, ambulances)

- understaffing and high workloads that increase patient frustration

- cultures that normalise ‘difficult patient behaviour’

- lack of consequences for patients, families or visitors who harass staff

- working with patients who have cognitive impairments or are under the influence of substances (Mikołajczak et al. 2024).

Using a risk-based approach involves the following three key steps:

Find and assess the risk of sexual harassment

Use different information sources to understand the when, where and how of sexual harassment in your organisation. This includes:

- talking with employees and employee representatives

- looking at internal reports, complaints data and audit results

- considering sector-wide trends and findings from national reports, such as Time for Respect: Fifth National Survey on Sexual Harassment in Australian Workplaces (AHRC, 2023b). These insights will help you find high-risk areas and do an industry-specific risk analysis.

Finding these risks lets you put in place targeted, preventive measures to avoid harm.

Put in place good control measures to address the risks found

Once risks are found, take practical steps to reduce them. Control measures may include:

- environmental changes – better lighting, more visibility in shared spaces, or security cameras

- process changes – updating or reinforcing behaviour expectations before work-related events and improving rostering practices, team structures and reporting pathways

All actions should be clearly recorded and reported to relevant staff.

Monitor, review and adapt control measures

Control measures should be regularly reviewed to make sure they still work. Ask questions like:

- Are the control measures working as intended?

- Have they been updated after an incident or near miss?

- Do they reflect any changes in workplace dynamics, structures or staffing?

This step is critical to making sure you keep improving and take a forward-thinking approach to prevention.

Key resources

- AHRC (2022) Good practice indicators framework for preventing and responding to workplace sexual harassment(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government: 6

- AHRC (2023) Guidelines for complying with the positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth)(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government: chapters 6.4, 6.7 & Appendix 3.

Step 3: Set up regular reporting and monitoring

Leaders (including boards, heads of organisations and executive teams) need regular updates on both the extent of sexual harassment and how well current systems to respond to it are working. This should be a key part of any organisation’s management of workplace health and safety.

Clear reporting helps keep leaders accountable, guides decision-making, and supports cultural change.

Internal reporting should cover:

- trends in formal and informal complaints

- risk areas needing targeted action

- progress on prevention and education programs

- outcomes and how long complaints take to resolve

- types of perpetrators, i.e., whether the harassment comes from a colleague, patients or clients, or another category.

When tracking complaint outcomes, it is important to monitor:

- whether the complaint was upheld or not

- if the complaint was moved to the Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission or the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal

- what happened to the person who harassed someone if the complaint was upheld

- how satisfied the complainant was with the complaint handling process.

Tips for public healthcare settings

Public health care organisations should pay special attention to monitoring:

- incidents involving patients, families and visitors – these often go unreported

- patterns of ‘difficult patient’ behaviour that may actually be harassment

- worker compensation claims for psychological injuries – these have increased 45% in Victorian healthcare from 2019-2022

staff turnover in high-risk areas like emergency departments and mental health services (Mikołajczak et al. 2024).

Include reporting in regular board meetings and other governance processes to make sure it is visible and actionable. Consistent monitoring and communication keep your organisation informed, engaged and committed to ongoing improvement.

Step 4: Build trust in your reporting systems

Build employee confidence that complaints will be handled fairly and respectfully. This means making sure your approach is:

- person-centred – support all people affected, both during and after the reporting process

- trauma-informed – provide specialised support, listen without judging and give people choice and control over how the organisation responds

- culturally safe – processes are responsive to the barriers faced by people affected by overlapping forms of inequality

- inclusive and fair – everyone involved in a report should get clear information about the process and outcomes as well as assurance of fair processes.

Employees should feel safe to report sexual harassment, knowing the process will support them and lead to meaningful outcomes. Victim survivors often say they just want the sexual harassment to stop and don’t want the person who harassed them to lose their job or be demoted (Equal Opportunity Commission of South Australia 2016). They may be reluctant to make a formal complaint if they don’t feel they’ll have a say in how the process develops and what outcomes are sought. For example, contributors to the Speaking from Experience report (AHRC 2025a) described systems that require rigid reporting formats or rely heavily on NDAs as silencing. Instead, organisations should ensure workers are given control, support, and respect throughout the reporting process.

Employees should have:

- multiple ways to report sexual harassment

- regular updates on the progress of their report

- clear resolution options tailored to the situation

- post-incident support, including a post-resolution plan to support individual and team recovery after an incident.

Communicate improvements clearly

Organisations should also clearly communicate with their workforce when they improve their formal reporting systems. Transparency helps build trust and accountability. When employees experience poor complaint-handling, they’ll likely tell colleagues. Telling your entire workforce about any changes you make is key to increasing their confidence in your ability to carefully and properly manage future complaints.

Your organisation should clearly communicate with employees about:

- how common and what type of workplace sexual harassment exists

- trends over time, including new risks or recurring patterns

- lessons learned through prevention efforts and risk reduction.

Key resource

- Champions of Change Coalition (2023) Building confidence and trust in workplace responses to sexual harassment(opens in a new window), accessed 1 April 2024

Offer alternative reporting options and resolution pathways

Not everyone will feel comfortable using formal reporting channels. Consider providing informal or anonymous options to lower barriers and encourage early reporting.

Flexible reporting options include:

- a digital and/or physical mailbox, or a hotline for anonymous complaints

- informal pathways that don't pressure employees to make a formal report.

Be clear about who may be told when an anonymous report is made and clearly describe any potential follow-up actions.

It’s also important to monitor trends in informal complaints to find emerging issues. While not perfect, these systems can help you find problems earlier and build trust in your organisation’s response (WGEA 2023: 16).

As well as formal investigations, consider alternative resolution pathways such as:

- local resolution helped by an immediate manager

- a guided discussion with a trained mediator or expert

- a formal investigation led by an independent investigator.

Offering flexible, person-centred reporting options increases accessibility and helps build trust in your organisation's response process.

Key resource

- Champions of Change Coalition (2023) Building confidence and trust in workplace responses to sexual harassment(opens in a new window), accessed 1 April 2024: 17 – 23

Step 5: Educate your workforce

Education is key to preventing sexual harassment. The new positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 requires employers to communicate what behaviour is unacceptable, how to recognise sexual harassment, and how to respond.

All your resources on sexual harassment should be accessible and written in plain language (AHRC 2025a: 44). The Australian Human RIghts Commission has recently produced a series of fact sheets and posters aimed at both employees and employers (see AHRC 2025b). These resources simplify key sexual harassment concepts and provide examples of how to communicate clearly with your workforce.

Develop a clear sexual harassment policy

Your policy should:

- communicate a zero-tolerance approach. State that sexual harassment is against the law and your organisation is committed to eliminating it

- give definitions, practical examples and case studies, including those involving technology

- explain where and to whom the policy applies – including off-site and work-related events

- set out the expected standard of behaviour across the organisation

- describe available supports for those who experience or witness harassment

- describe the reporting process, possible outcomes, and your organisation’s commitment to a person-centred, trauma-informed response

- reference your organisation’s risk management framework

- say who is responsible for the policy and when it will be reviewed.

Provide ongoing training

Training also plays a key role in reinforcing your sexual harassment policy and supporting cultural change. Workplace education should:

- explain the options for reporting and potential outcomes

- communicate a zero-tolerance approach to sexual harassment

- use a mix of formal and informal learning methods, tailored to your organisation

- be ongoing, with a focus on quality, accessibility and effectiveness – not just frequency

- include interactive bystander intervention training

- use realistic case studies and examples relevant to your workplace.

Tips for public health care settings

Public health care-specific workplace education should also include:

- how to manage harassment from patients, families and visitors

- recognising when ‘challenging patient behaviour’ is actually harassment

- de-escalation techniques for difficult situations

- how to work safely in isolated environments

- understanding cognitive impairments and how they may affect patient behaviour

bystander intervention when patients harass colleagues (Mikołajczak et al. 2024).

Key resource

- AHRC (2023) Guidelines for complying with the positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth)(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025: chapter 6.3

- AHRC (2025b) Workplace sexual harassment resources, AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 30 June 2025. (opens in a new window)

Step 6: Create a respectful culture

Workplaces that are diverse, respectful and inclusive are less likely to tolerate sexual harassment.

Promote a culture that:

- reinforces zero tolerance for inappropriate or disrespectful behaviour

- champions respectful leadership and peer behaviour at all levels.

A strong culture sets clear expectations and helps make sure that inappropriate conduct is addressed early and consistently. Your organisation can take forward-thinking steps to strengthen culture by:

- increasing representation of underrepresented groups through recruitment, training and development

- making sure leaders and managers model respectful behaviour, use inclusive language, and reinforce the organisation’s commitment to diversity and inclusion

- calling out inappropriate conduct, including in digital communications such as online chats and messages

- providing training that encourages employees to see and challenge inappropriate behaviour, including everyday sexism.

Tips for public health care settings

- Public health organisations can also strengthen culture by educating patients, families and visitors about respectful behaviour. This could include:

- clear signs and information explaining that harassment of staff is unacceptable

- educational materials for patients and families about appropriate behaviour

- consistent consequences for patients, families or visitors who harass staff

- working with community groups to promote respect for healthcare workers

public awareness campaigns that healthcare workers deserve to be safe at work (Mikołajczak et al. 2024).

Key resources

- AHRC (2023) Guidelines for complying with the positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth)(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025: chapter 6.2

- AHRC (2022) Good practice indicators framework for preventing and responding to workplace sexual harassment(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 1 April 2025: 5

Leadership accountability

Leaders play a key role in preventing and addressing sexual harassment. Their actions shape organisation culture and directly influence outcomes.

Leaders should be responsible for:

- setting the tone on respectful behaviour and workplace norms

- supporting forward-thinking policies and procedures

- championing diversity, inclusion and belonging (Hart et al. 2018; Perry et al. 2020)

- providing resources to build organisation skills and capability.

Your organisation’s governance framework should clearly describe leaders’ responsibilities for preventing and responding to sexual harassment. This includes linking these responsibilities to performance assessment and saying what consequences happen when people do not meet expectations.

Senior leaders should play an active role in developing, putting in place and regularly reviewing control measures. They should also lead cultural change by communicating the importance of a respectful, diverse and inclusive workplace, and by sharing the organisation’s progress in eliminating sexual harassment.

Sexual harassment data should be regularly reported to your governing body and to those responsible for developing and overseeing control measures.

Key resources

- AHRC (2023) Guidelines for complying with the positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth)(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025: chapter 6.1

- AHRC (2022) Good practice indicators framework for preventing and responding to workplace sexual harassment(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 1 April 2025: 2-3

Step 7: Address technology-facilitated sexual harassment

Workplace technology-facilitated sexual harassment is a growing workplace risk. As digital tools change, so must your prevention strategies. Tailor your approach to reflect how technology is used in your organisation and focus on safety at every level (Flynn et al. 2024).

Choose technology that focuses on safety

Workplace tools – such as chat platforms and email systems – should be designed with safety in mind. Look for platforms that include:

- built-in safety features that detect and flag inappropriate content

- AI-powered prompts that notify senders of potentially inappropriate language

- alerts for recipients, providing immediate access to reporting tools and support pathways.

These safety-by-design features help shift the burden away from employees and create a forward-thinking, prevention-focused environment (Flynn et al. 2024).

Update polices and training

Review and update policies and training to:

- define what technology-facilitated sexual harassment looks like in your context

- clarify potential outcomes for those who engage in it

- make sure your reporting processes can handle digital incidents

- deliver education that reflects current risks – including tailored training on bystander action, digital conduct and respectful communication.

Take an ongoing approach

Preventing sexual harassment – including digital forms – requires ongoing commitment. There’s no single ‘set-and-forget’ solution. Organisations should:

- stay up to date with best practices in their sector

- learn from others through communities of practice

- monitor and review internal processes regularly

- foster a culture of continuous learning and change.

Long-term progress means being open to feedback, adjusting your approach, and understanding that lasting change takes time and persistence.

Key resource

- Flynn A, Powell A and Wheildon L (2024) Workplace technology-facilitated sexual harassment: Perpetration, responses and prevention(opens in a new window), ANROWS, accessed 9 April 2025

Footnotes:

- The relevant section of the Commission’s workplace gender audit guidance(opens in a new window) has further information about formal complaints data.

Resources

This page provides references for sources used throughout this report.

Australian College of Nursing (2020) The Sexual Harassment and/or Sexual Assault of Nurses by Patients(opens in a new window), accessed 9 April 2025.

AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission) (2020) Respect@Work: Sexual Harassment National Inquiry Report(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 9 April 2025.

AHRC (2022) Good practice indicators framework for preventing and responding to workplace sexual harassment(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 1 April 2025.

AHRC (2022a) Guidelines on the use of confidentiality clauses in the resolution of workplace sexual harassment complaints(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025.

AHRC (2022b) Time for respect: Fifth national survey sexual harassment workplaces(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 9 April 2025.

AHRC (2023) Guidelines for complying with the positive duty under the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth)(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025.

AHRC (2025a) Speaking from experience: What needs to change to address workplace sexual harassment(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 25 June 2025.

AHRC (2025) Workplace sexual harassment resources(opens in a new window), AHRC, Australian Government, accessed 30 June 2025.

Bell M, McLaughlin M and Sequeira J (2002) 'Discrimination, harassment, and the glass ceiling: Women executives as change agents', Journal of Business Ethics, 37(1):65–76.

Champions of Change Coalition (2023) Building confidence and trust in workplace responses to sexual harassment(opens in a new window), accessed 1 April 2024.

Cho H and Segrave M (2023) Victorian local councils and gender equality: Examining commitments to diversity and the experiences of women from migrant and refugee backgrounds(opens in a new window), Monash University, accessed 9 April 2025.

Comcare (2020) Workplace sexual harassment: practical guidance for employers(opens in a new window), Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025.

Comcare (2024) Systems for respect: interventions to reduce workplace sexual harassment(opens in a new window), Australian Government, accessed 7 April 2025.

CGEPS (Commission for Gender Equality in the Public Sector) (2023) Intersectionality at work: Building a baseline on compounded gender inequality in the Victorian public sector, CGEPS, Victorian Government, accessed 9 April 2025.

Equal Opportunity Commission of South Australia (2016) Sex Discrimination, Sexual Harassment and Predatory Behaviour in South Australia Police: Independent Review, Government of South Australia, accessed 9 April 2025.

Flynn A, Powell A and Wheildon L (2024) Workplace technology-facilitated sexual harassment: Perpetration, responses and prevention, ANROWS, accessed 9 April 2025.

Gabay G and Tikva S (2020) ‘Sexual harassment of nurses by patients and missed nursing care-A hidden population study’, J Nurs Manag, 28(8):1881-1887, doi: 10.1111/jonm.12976.

Hart C, Crossley A and Correll S (2018) 'Leader messaging and attitudes toward sexual violence', Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 4:1–13, doi: 10.1177/2378023118808617.

Liang T (2024) ‘Sexual Harassment at Work: Scoping Review of Reviews’, Communication Studies, 76(2):143-163, doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S455753.

Mackinnon C (1979) Sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination, Yale University Press, New Haven.

McFarlane A, Bridges D and Maria S (2025) The culture of everyday sexism and gender inequality in the paramedicine profession. A qualitative study, Paramedicine, 0(0):1-10, doi:10.1177/27536386251330950

Mikołajczak G, Barry I, Summerhayes E, Ryan M, Baird M, Barr N and Shepard B (2024) Work-related gendered violence against Victorian healthcare workers: A review of the literature, Global Institute for Women's Leadership, Australian National University.

Our Watch (2025) Sexual harassment response a key issue in attracting and retaining staff, new data shows(opens in a new window), Our Watch, accessed 7 April 2025.

Our Watch (2021) Change the story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women in Australia (second edition), Our Watch, accessed 23 April 2025.

Perry El, Block CJ and Noumair DA (2020) Leading in: Inclusive leadership, inclusive climates and sexual harassment’, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 40(4):430-447, doi:10.1108/EDI-04-2019-0120.

Robinson KH, Allison K, Jackson EF, Davies C, Smith EK, Hawkey A, Ussher J, Ullman J, Marjadi B and Byron P (2024) #SpeakingOut@Work: Sexual harassment of LGBTQ young people in the workplace and workplace training, ANROWS, accessed 9 April 2025.

Safe Work Australia (2023) Model Code of Practice: Sexual and gender-based harassment(opens in a new window), Safe Work Australia, accessed 7 April 2025.

Safe Work Australia (2023a) Sexual and gender-based harassment: Code of Practice, Safe Work Australia, accessed 1 April 2024.

Smith B (2023) ‘Respect@Work amendments: A positive reframing of Australia’s sexual harassment laws’ 36 Australian Journal of Labour Law 145.

UN Women (2024) UN Women ending violence against women and girls: Knowledge products, guidance and tools, 2022–2024(opens in a new window), accessed 1 April 2025.

Wescott S, Phelan A, Pfitzner N, McCook S and Roberts S (17 October 2024) 'Victorian students will get ‘anti-Tate’ lessons – but much more is needed to tackle gendered violence in schools', The Conversation, accessed 7 April 2025.

WGEA (The Workplace Gender Equality Agency) (2023) Using evidence to improve workplace sexual harassment prevention and response: Guidance for employers, Workplace Gender Equality Agency, accessed 1 April 2025.

WGEA (2023a) Policy and strategy guidance: Workplace sexual harassment, harassment on the ground of sex and discrimination(opens in a new window), Workplace Gender Equality Agency, accessed 7 April 2025.

Sojo V, Ryan M, Fine C, Wheeler M, McGrath M, Glennie M, Roberts V, Arthur L, Hadoux R and Western K (2022) What works, what’s fair? Using systematic reviews to build the evidence base on strategies to increase gender equality in the public sector, The University of Melbourne, The Australian National University, and Swinburne University of Technology, accessed 9 April 2025.

Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (2015) Independent review into sex discrimination and sexual harassment, including predatory behaviour in the Victoria police: Phase one report(opens in a new window), accessed 8 April 2025.